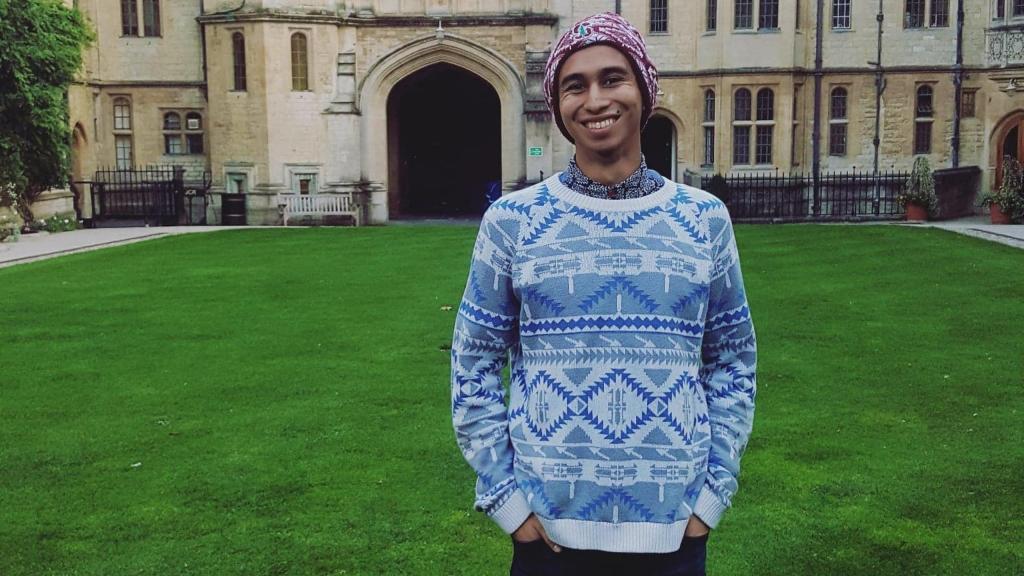

‘Tell me the story of your life.’ Alex Fuentes listens deeply as part of the American Voices Project

Stanford and Princeton, with support from a coalition of partners including the Federal Reserve Banks, began the American Voices Project as a way to study poverty. It’s grown into a rich archive of individuals’ stories researchers can use as a resource.

By

After the initial pleasantries and introductions, every research phone call Alex Fuentes made for the American Voices Project started with the same request. It’s one most people have never heard:

“Tell me the story of your life.”

Resulting interviews usually lasted at least an hour and sometimes more than two. Fuentes interviewed about 25 people for the project.

Many of them said the same thing: “I’ve never told anyone this before.”

Stanford and Princeton universities have led the American Voices Project, with support from the Russell Sage Foundation, the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, Boston, Cleveland, Dallas, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, and San Francisco, and other partners. They work to build an understanding of the day-to-day experiences of individuals and families in communities across the country. The project began as a way to study US poverty. It has grown into a trove of personal narratives similar, in some ways, to StoryCorps, the widely known public effort to collect and archive individuals’ personal histories. Interviews conducted over the past year also serve as an oral history of how people across the country weathered the pandemic.

“We want to have an on-the-ground understanding of what’s happening to individuals and families throughout the country as they live their lives under often harrowing circumstances,” said David Grusky, a Stanford sociology professor and a member of the team running the project.

During the interview phase, researchers, including Fuentes, talked to more than 2,500 people from about 300 communities across the country. Interview subjects were pulled from a random sample; each participant received a letter in the mail from Stanford telling them they’d been selected. Collectively, those interviews comprise what Grusky said is the largest qualitative research project he knows of.

Never miss a story.

The seeds for the American Voices Project were planted 10 years ago. The federal government, which at the time funded three national centers to study poverty, charged researchers at the centers with devising a new way to do qualitative research. Grusky and Kathryn Edin, of Princeton, who were both working with the centers, came up with the idea of creating a database of interviews available to other researchers.

“The old model incorporated gathering data, publishing research, and ultimately throwing the data out,” Grusky said. “We’ve been committed from the start to a new type of qualitative work. It’s a dataset that’s open to others to analyze, to make sense of, to check the conclusions of others.”

Executing such an ambitious project would require planning, patience, and Olympic-level listening skills—the kind of skills Fuentes, who graduated from Stanford in the spring, already had.

From the American Voices Project

It took a pandemic…

Expanded assistance, material hardship, and helping others during the Covid-19 crisis

What’s weighing heaviest

Indirect health consequences of the Covid-19 crisis

The rise of the noxious contract

Job safety in the Covid-19 crisis

Having to stay still

Youth and young adults in the Covid-19 crisis

Interview mode

Asking someone for their life story and listening for hours as they tell it builds trust, even over the phone. The interviews could be intense, Fuentes said, covering individuals’ personal lives, political views, and value systems.

The quick version of Fuentes’ own life story might go something like this: Fuentes was born in Long Beach, California. “My mother was a single teen mom,” he said. “She always emphasized school and getting an education. We lived with my grandparents, who helped raise me. We moved around a lot.

“My grandmother was from Guatemala and my grandfather was from Mexico,” he said. “My grandmother worked as a housecleaner and used to sell Avon, while my grandfather often worked odd jobs, eventually building up to his own handyman business. I never met my biological father, but my grandparents played a key role in my life. My mom has largely been a stay-at-home mom for me and my two brothers.”

Fuentes excelled at school. When he got into Stanford University, he said the custodians and dining hall workers, many of whom are Latino, reminded him of home. “They would encourage me and other students to ¡échale ganas! (Give it all you’ve got!),” he said. “My grandfather passed away my freshman year in college, so I often found solace in Stanford’s service workers.”

Fuentes majored in psychology, studied abroad in Florence and Oxford, and worked with a veterans group and the National Alliance on Mental Illness. A course his senior year, “Monitoring the Crisis,” in which students did immersive interviews with people across the country about how the pandemic crisis affected them, led Fuentes to apply as an interviewer with the American Voices Project. He was intrigued by its focus on storytelling.

“I’m a big proponent of the power of stories to influence change,” Fuentes said. “I grew up in a storytelling culture. My family would often tell me stories about their upbringing.”

Stanford selected its American Voices Project interviewers from a group of applicants well-versed in research methods. The selection process was highly competitive; Grusky joked that it’s harder to become an American Voices Project interviewer than it is to get into Stanford itself. Interviewers are selected for their empathy, openness, and interest in understanding others.

For Fuentes, this was his first post-college job, and the skills he honed are sticking. Now, “even with old friends, sometimes when they confide in me, I’ll find myself in interview mode,” Fuentes said.

That habit of digging for more information is likely to come in handy at his new role. Fuentes was named a Coro Fellow in San Francisco. During the one-year fellowship, participants do rotations in public- and private-sector organizations to gain a better understanding of how they work.

“I’m so grateful to the participants in the American Voices Project,” Fuentes said. “They’re entrusting us with their experiences, their stories. It can be very healing for people.”

American Voices Project began conducting interviews in 2018, with support from partners including a coalition of regional Federal Reserve Banks, the Russell Sage Foundation, and others. The dataset of interviews will be open to other researchers; the project’s next step is a public call for submissions of research proposals.