The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic cost parents of small children dearly in terms of financial wellbeing. Just 67 percent of parents surveyed in 2020 said they felt they were doing “at least okay financially.” When the survey ran again in 2021, that figure jumped to 75 percent of parents. A key factor accounting for that difference is parents having a safe, adult-supervised environment for their children while they work. In 2021 many child care workers returned to their essential roles, enabling these parents in turn to go back to work.

Clearly, child care is vital to supporting the financial wellbeing of workers, households, and communities. But despite their essential role in the economy, child care workers long have faced barriers to being fully seen and valued at work, let alone being fairly treated and compensated for their work.

How do we ensure that care work of all kinds is visible as an essential sector, rather than solely recognized and valued when it disappears? And how do we sustain the viability of care work writ large, preventing the field of work and its providers from becoming invisible once again as the world returns to “normal”?

Child care work is vital economic infrastructure

The Federal Reserve Board conducts an annual survey of household economics and decisionmaking, from which it produces a report each spring with summary findings and analysis. The Board’s Economic Well-Being of US Households in 2020, based on the survey conducted in October and November 2020, reported that one-fourth of all parents, and six in 10 who used child care services, experienced disruptions to their child care as a result of the pandemic.

Twenty-two percent of all parents also reported they were working less or not at all because of disruptions to childcare or in-person K-12 schooling. Parents with children under the age of 18 reported a relatively steeper decline in overall financial well-being that year compared to other adults (Figure 1).

Figure 1

That trend changed by late 2021, however, with gains that surpassed pre-pandemic levels of overall financial well-being. How?

When child care workers were able to return to their roles after pandemic lockdowns were lifted, many parents were relieved of their full-time child care responsibilities. According to the Federal Reserve’s Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021, this return to needed child care coverage in turn led to a marked increase in parents’ overall financial wellbeing.

Care workers are paid less, have fewer benefits and protections

The pandemic demonstrated that it is important to invest in this critical child care work infrastructure to support parents’ financial wellbeing. Yet it also points to the need to design workforce policies to recognize and reward the wider economy-supporting work of those who provide care to both children and adults. These individuals enable others to stably serve in their own roles elsewhere in the workforce.

During the Federal Reserve Board’s 2021 Gender and the Economy Conference, Ai-jen Poo, president of National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), summarized the role of care workers: “It’s the nannies, it’s the house cleaners, and it’s the home care workers who take care of the aging and people with disabilities inside of the home and allow them to live independently in the community.”

She also noted that care workers comprise a “workforce that is more than 90 percent women and majority women of color.”

Yet these vital workers contend with a system that leaves them unprotected at work. They have long been excluded at the federal policy level from key rights such as paid sick leave and recourse in the case of on-the-job sexual harassment—protections that have been extended to most other occupations in the workforce since the 1930s through the Fair Labor Standards Act.

These exclusions fuel inequalities built into the care work system, and which are compounded because women must depend on other women to be able to work. The Federal Reserve Board reported that in 2020, child care responsibilities already prevented many mothers from entering or fully participating in the labor force. The pandemic made it even harder for women with children to work. One quarter of mothers said they were unable to work as many hours as they did before the pandemic or even work at all due to disruptions in child care or in-person K-12 schooling. Only 18 percent of fathers faced the same challenges.

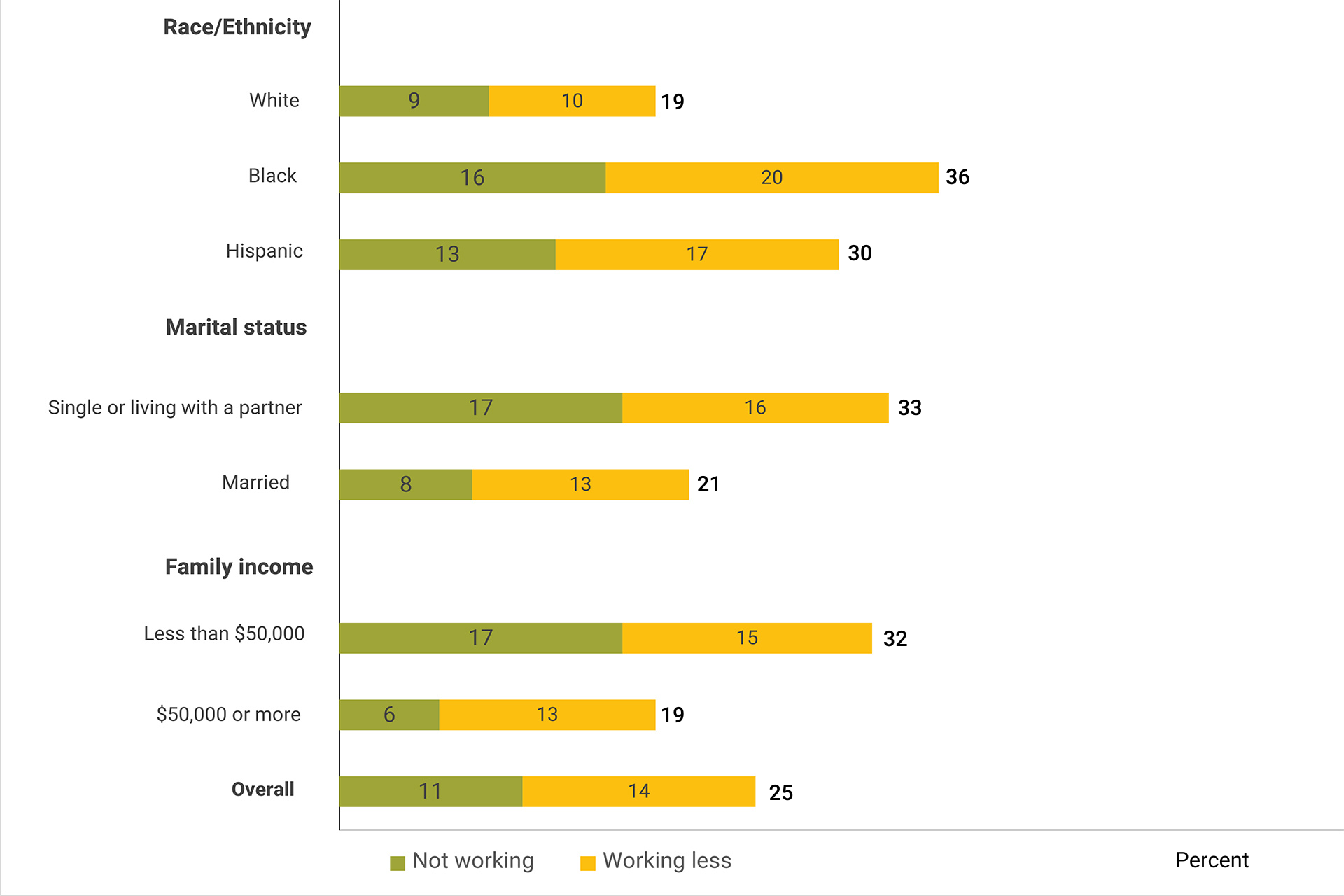

For Black, Hispanic, and single mothers and mothers earning low incomes, the pandemic’s impact on their ability to work was even more pronounced (Figure 2).

In 2021, these differences between mothers and fathers persisted. Six percent of women versus only one percent of men cited child care as a reason for not working, and 10 percent of women cited other family responsibilities versus only five percent of men.

Figure 2

Reduced hours worked or not, working due to childcare or school disruption amongst mothers (by race/ethnicity, marriage status, and family income

The women performing the child care work are also often dependent on the system in which they work. Costs have gone up for child care in recent years, putting added pressure on those who provide care for other workers’ children to ensure their own kids are safe and cared for while they work.

Paulina López González, economist-in-residence at NDWA Labs, the innovation arm of the NDWA, said that the challenging situation child care workers are in “comes from undervaluing care work and domestic work generally as a society.”

Public investment in care workers to reflect their crucial roles in the economy

Because care workers of all kinds historically have been excluded from important worker benefits and protections, they face even greater challenges than some other workers who earn low wages.

“We as a society can bring value and push for the respect and the dignity of the work,” González said. “These workers—women or men—should have fair wages and paid time off and sick days.”

“The fact is child care workers are some of the lowest paid in the country, [yet] we challenge them and depend on them to protect our most precious cargo. Where is the common sense in that?” added Christie McCravy, executive director at the housing trust fund and vice chair of the Federal Reserve’s Community Advisory Council.

Relieving the strain of care workers outside of their jobs would also support their vital work. Organizations such as Louisville Affordable Housing Trust Fund are working on a range of initiatives to provide affordable housing, and McCravy is focused on ensuring equitable standards for the housing qualification process to include care workers.

“If these women are coming to work stressed because they can’t afford their rent, they can’t provide the best for the children they are to care for,” said Christie.

Ensuring the viability of “job-sustaining jobs”

Valuing care work requires a multi-pronged approach that centers the needs of care workers and their clients. Future care work that’s sustainable involves inclusive policies, a stronger network of relationships, and supportive programs designed to have immediate benefits on the wellbeing and financial outcomes of everyone involved, especially care workers.

Such an approach would deliver positive, longer-term impacts on children overall. Doing so also envisions a society that demonstrates how supporting women and mothers enables a healthy and vibrant workforce.

Investing in public supports for care workers helps to demonstrate the importance of their labor and “begin the shift of narratives and how we think about this workforce,” NDWA Labs’ González said. “After all, these are job-enabling jobs.”