Regular exposure to even small amounts of lead endangers health. For children, lead presents a risk of developmental delays and long-term behavior and learning problems. And yet every day, millions of people are potentially exposed to lead through an estimated 6 to 12 million lead service lines (LSLs) that supply drinking water to homes, schools, and other facilities.

New federal funding and recent changes to federal and state laws may encourage or require water systems to stop waiting for crises and make plans for rapid replacement. Yet more widespread and rapid LSL replacement will present new financial challenges.

Addressing these challenges is critical for the Upper Midwest, where LSLs are particularly prevalent. Low-income neighborhoods and communities of color are also heavily impacted, facing higher concentrations of LSLs as well as greater economic barriers in efforts to replace them.

Keys to resolving barriers to LSL replacement

Eliminating lead exposure in drinking water requires replacing LSLs with new pipes. According to 2016 US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates, on average it costs $4,578 for water systems and $3,559 for property owners per LSL to make this swap.

LSL replacement has been slow and sporadic, often only occurring in reaction to a crisis. How can cities speed up the process? The first challenge is that municipalities, water systems, property owners, and private investors must resolve two key issues to make meaningful strides toward LSL replacement:

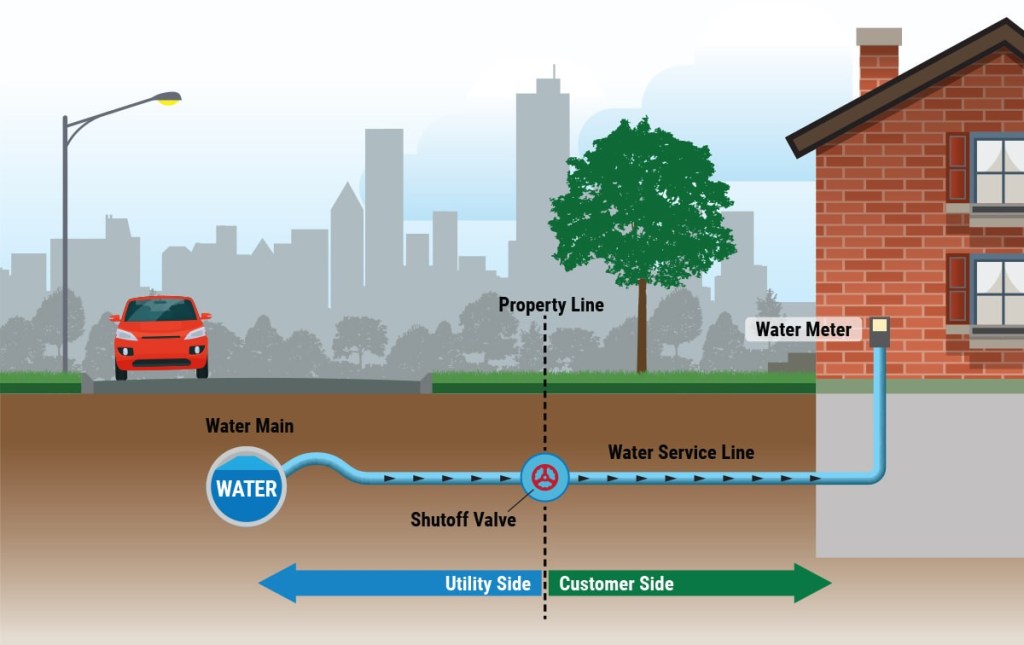

- Eliminate coordination challenges, so that when the local water system and property owners share ownership of lead service lines, they are able to work more easily and effectively together to replace LSLs; and

- Create incentives for those in the position to replace LSLs, so that the benefit to them outweighs the cost of replacement. Often, those who are the most impacted by LSLs (renters, children) have the least amount of power to replace them, so incentivizing those who do have that power (municipalities, water systems, property owners, and investors) could have a large, positive impact on LSL replacement.

Funding challenges for LSL replacement

The second major challenge is finding funding for LSL replacement. Even with available federal funding for faster and more widespread LSL replacement at an unprecedented level, it still falls short of the total cost. Although federal appropriations in late 2021 dedicated $15 billion to LSL replacement, this amount is less than half of the national cost estimates.

Without additional federal or state funding or philanthropic grants, resolving the funding gap will likely require water systems to borrow money from private investors. But that funding route imposes costs on private citizens who must repay the debt by paying more for water. In the lower-income communities—most impacted by the LSL problem—such costs can be too much to bear.

Investing in equitable solutions can benefit everyone

There’s a chance that resolving the LSL issue could further worsen existing racial and economic inequities, as those most negatively impacted by lead service lines are the least likely to be able to afford to replace them. One meaningful way to mitigate inequitable solutions is to prioritize the experiences and outcomes of those most impacted. For instance, water systems that proactively replace LSLs in low-income communities each year at no expense to property owners is one such example of a more equitable solution.

There are vast benefits in reducing lead exposure, including improved health, reduced health care costs, increased educational achievement and incomes, longer life spans, and improved quality of life. Investing in equitable LSL replacement solutions offers positive impacts likely to ripple out across communities for years to come.

Visit the Chicago Fed for more about the lead service line issue and possible solutions.