On a crisp fall day, residents of the Wendell Phillips Downtown East neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri, began arriving for a conversation about community improvement. The neighborhood association recruited 30 residents for dinner and conversation at a nearby nonprofit. The purpose of the gathering: to discuss broadband and why residents did or did not subscribe.

What residents said that night revealed why so few people in many urban neighborhoods subscribe to broadband—and surprised even people with years of experience tackling the digital divide.

Their answers are particularly timely, too, as states consider how to spend billions of dollars to expand broadband access. This modest gathering was a chance to amplify the voices of residents in this Kansas City neighborhood and potentially inform policy nationwide.

“We can report numbers all day long, but those personal stories are so important”

The planning team included aSTEAM Village, the nonprofit; the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City; and the Wendell Phillips Neighborhood Association, with involvement from the Kansas City Public Library. Together, the partnership provided deep roots in the neighborhood, extensive knowledge of broadband, and connections with local and national broadband policymakers. This was a pilot project, part of a System-wide effort to increase the use of community-engaged research in the Federal Reserve.

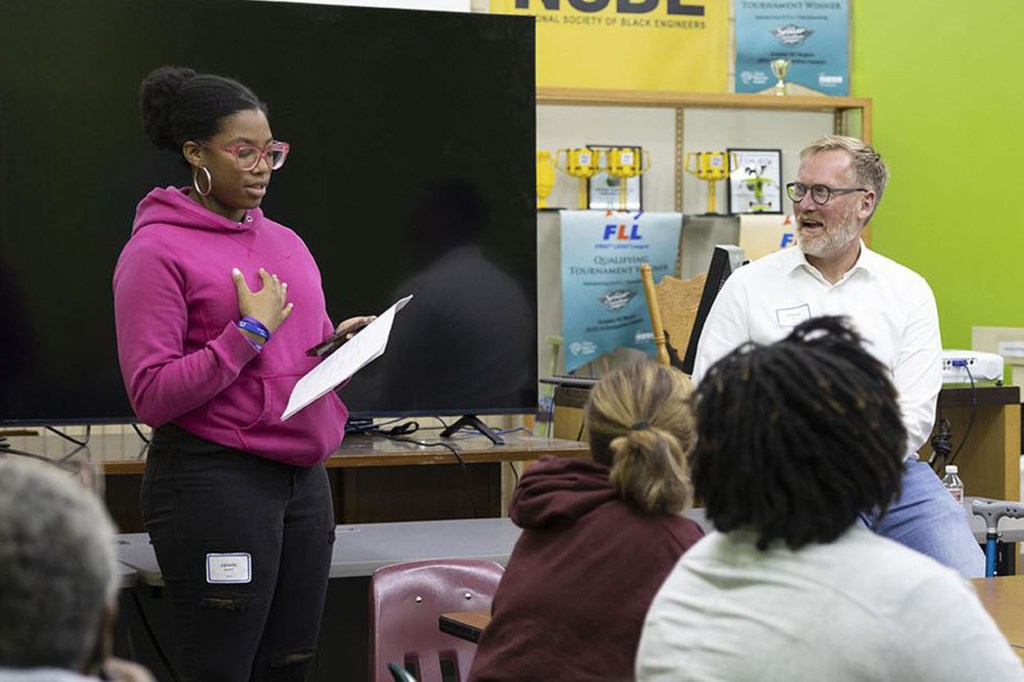

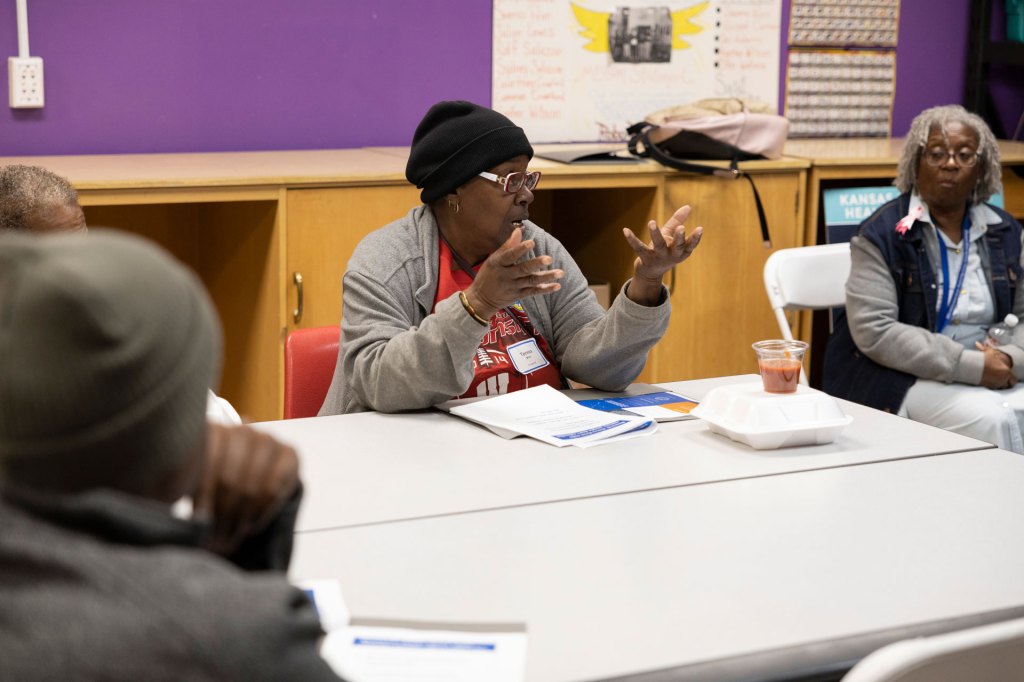

The format for the gathering was a data walk, an innovative way to share data with communities. The Urban Institute developed the data walk tool and also served as a technical advisor.

After hearing the neighborhood president explain the importance of the conversation about broadband, participants divided into small groups. Facilitators in each group asked residents about their subscription preferences and speed and price availability compared to those of nearby neighborhoods. Residents also saw an area map indicating where broadband subscription rates were low.

“This experience really opened my eyes, even having worked directly with community members over the past seven years,” Wendy Pearson said. Pearson is strategic initiatives director for the Kansas City Public Library and a member of the planning team. “We can report numbers all day long, but those personal stories are so important.”

Most residents who did have internet said the service was unreliable, cutting out for a day or more. One resident relies on her Ring doorbell for a sense of safety. She reported that when her internet goes down, she doesn’t feel safe. “That blew my mind,” Pearson said.

Residents also see reliable, affordable broadband as critical to the future of the next generation. “These kids will do jobs we haven’t even thought of. I’m interested in the intellectual capacity of our kids to be fully recognized,” noted one participant. “Driving the electric vehicle is one thing, but imagining it is something else.”

Themes affecting the digital divide

Following the gathering with Wendell Phillips residents, the research team released Crossing the Divide: What we learned from a disconnected neighborhood. The report explores the findings and additional research that help put these findings into context. The conversation produced three themes related to their neighborhood: historical and continued disinvestment, trust, and community empowerment.

Being a historically redlined and disinvested neighborhood comes with ongoing challenges. A recent study found that four national internet service providers (ISPs) routinely charged residents of different areas the same amount despite different speeds of internet. They offered internet speeds up to 200 Mbps in majority non-Hispanic white neighborhoods for the same price they charged consumers in historically redlined neighborhoods for 25 Mbps internet.

Given ISPs’ tiered pricing, limited service availability, and unclear communications, few residents trust ISPs to serve their best interests.

“It doesn’t feel good that we’re second class and our needs are not worth investing in,” one participant said. It’s clear that residents want to better understand technology. They have a keen desire for digital skills training, from basic to advanced levels. They also want to help shape solutions in their neighborhood.

Involving the people affected by a problem to help find solutions lies at the heart of community-engaged research. But that engagement hasn’t often happened.

“The money that comes into our neighborhood to fix a problem is given to the people that profit from creating the problem,” said John James, president of the Wendell Phillips Neighborhood Association. “When we talk about communities, we talk about them from the top down. The problem will not be solved if we ask the people who caused the problem to validate the solution.”

Understanding the digital divide

The moment people started using the internet, a divide emerged between those who could access it and those who could not. Decades later, this divide still exists.

“Real lives are at stake here,” Williams Wells said. Wells is executive director of aSTEAM Village. “What gets to me is it didn’t have to be this way. It’s all a system design problem that millions of dollars have been thrown at over the years.” The conversation with Wendell Phillips neighbors helps show that when we really understand the causes of the digital divide, we can solve the problem.

“These kids will do jobs we haven’t even thought of. I’m interested in the intellectual capacity of our kids to be fully recognized.” – Participant

Author’s note: The Kansas City Fed planning team also included Jeremy Hegle, assistant vice president and Community Affairs Officer and Steven Howland, associate economist for the community development department.