A hand up,

not a handout,

to cross the benefits cliff

Losing public assistance benefits when their income goes up incentivizes some workers to stay in low-paying jobs. It discourages others who are willing to work from joining the workforce. New strategies aim to identify and address this benefits cliff that hinders entry to and advancement in the workplace, though work to address the issue on a larger scale remains.

By Gabriella Chiarenza, Fed Communities

December 2, 2022

Deonne Luacaw in Quincy, Massachusetts. Photo: Steve Osemwenkhae

Deonne Luacaw had plenty of reasons to be excited about her new job this fall—and one reason to be very worried.

A single mother of two living just outside Boston, Luacaw landed a position as a data clerk with a major health insurance company, the first full-time, well-paying job with a career path that she’d had in a decade. She teared up as she talked about how much her new job will affect her life.

“Last year, I didn’t have income, so you have to sign up for all the food pantries for Thanksgiving dinner, and for presents [for Christmas],” she said. “Now, I know that I can get my son that bike he wants for Christmas because I do have a job. I can do nice things. It’s a big deal, it really is.”

But Luacaw’s new job also comes with a significant hitch.

Public assistance benefits, which help Luacaw and others with moderate earnings afford basic needs like food, housing, child care, and health care, are tied to a recipient’s income. Those benefits logically start to fall away once someone gets a job and starts earning more money. The idea is that as income goes up, a smaller amount of public assistance is needed to cover basic costs.

But there’s often a gap between what someone will be earning in a new job and the value of the public assistance benefits that person loses as a result. This mismatch is called the “benefits cliff” or the “cliff effect.” The threshold for cutting off assistance for a benefit frequently is lower than the amount someone needs to earn to replace that benefit.

Sometimes people reach a benefits “plateau,” where each additional dollar they earn costs them a dollar in assistance, making the additional earnings a wash for their net income. A benefits plateau can feel like running in place: not falling behind, and yet never getting ahead, either. Both cliffs and plateaus can continue for years for some individuals.

In Luacaw’s case, her worry regarding the new job stemmed from the uncertainty in calculating her expenses and net income. “I know my rent is going to go up a couple hundred dollars. I’m going to lose my food stamps. I get $600 [a month] in food stamps and I’m probably going to lose 90% of that,” she said. “The money that I’m [earning from] working has to go and cover those expenses. Once I get my first paycheck, DTA [the Department of Transitional Assistance] automatically knows I’m working, so my benefits get cut down.”

In other words, a new job like the one Luacaw found can pay enough to disqualify someone from receiving benefits, but not enough to replace or surpass what’s being lost.

Terms to know

Benefits cliff

Gap between what someone will be earning in a new job and the value of the public assistance benefits that person loses as a result.

Benefits plateau

When each additional dollar someone earns costs them a dollar in public assistance, resulting in no change to their net income.

The danger of falling over a benefits cliff

Instead of reaching financial stability, people like Luacaw who get some or all of their financial support from public assistance can end up worse off after joining the workforce, accepting a pay raise or promotion, or moving to a better-paying job.

Public benefits in the United States are financed by taxes, mostly federal, some state and local. Typically, these benefits are divided into separate, standalone programs to cover some of the costs of food, housing, health care, child care, and so on. Most programs are administered by states, which may make their own rules for individual programs regarding income qualifications and when benefits start to taper or end completely.

The benefits cliff has stubbornly persisted, in part because of the sheer number and complexity of aid programs. The public assistance landscape in the United States is a jigsaw puzzle of programs that may be pieced together in many different combinations, depending on a household’s location, composition, qualifications, and needs.

This complex landscape also makes it impossible to say for certain how many people in the United States are impacted by the problem. Who ultimately runs into the cliff effect varies widely across different states, and, for reasons discussed below, it’s hard to find comprehensive data on the issue.

Still, chambers of commerce and workforce agencies have fielded surveys that provide some sense of the impact on workers and businesses. In Ohio, for instance, almost one in five employers responding to a survey said that they had seen employees refuse raises or job offers because of benefits cliff concerns. In a survey of unemployed and underemployed people in Alabama, over a third of respondents had turned down a job or promotion due to benefits cliff threats. And a Florida survey found that a third of businesses reported employees turning down raises or additional hours.

“The benefits cliff can affect people with incomes up to about $60,000 a year,” according to Dave Altig, director of research at the Atlanta Fed and a leader in the central bank’s work on this issue. “A substantial part of people in the wage distribution are potentially impacted by this.”

The benefits cliff can affect people with incomes up to about $60,000 a year.

Sometimes recipients are alerted when they’re approaching a benefits reduction. In other cases, they’re blindsided, unaware they’ve reached a benefits cliff until they report an increase in their income to the agency that issues their benefits.

Exceeding income limits can cause swift, jarring impacts to ripple out from what would otherwise be an exciting work transition. A change to or loss of benefits may mean that suddenly, a family can no longer live in the same housing unit or send their child to the same child care program.

The threat of these impacts can have a chilling effect on assistance recipients’ willingness to enter or re-enter the workforce or accept promotions. Their decisions in turn have impacts on employers and the entire economy.

Ripple effects from the benefits cliff touch everyone in the economy

Altig noted that it’s in the economic interest of all of us for more people to be working and paying taxes as opposed to drawing on tax dollars because they must rely on benefits. Those overall advantages to the economy only grow when more working people are able to move into higher-paying jobs with career paths.

The benefits cliff discourages people who want to work from doing so, though, because moving into or up within work doesn’t pay for those trying to get off public assistance.

It’s a seeming contradiction stemming from a problem at the heart of the public assistance benefits system. While that system provides for people who need help in moments of crisis, it does not provide a stable path out of reliance on benefits when someone is ready to step into the workforce. Making the transition is therefore a huge risk.

Altig put this contradiction in stark terms: “It’s a disincentive for people to come to work if they are out of the labor force,” he explained. “It’s a disincentive for them to work more if they are in the labor force. And it is very much a disincentive for them to skill up and invest in their own economic mobility and resilience as a consequence of that.

“There’s a very well-established notion of what uncertainty does in economics generally,” Altig added, “and what uncertainty does is keep people on the sidelines.”

And when uncertainty means people losing benefits are essentially forced to stay on the sidelines to be sure they can provide for their families, that makes it much harder for businesses to find workers and to retain and promote higher-performing employees.

“There are critical talent needs and there is a subset of individuals that may be really well positioned to meet those talent needs but for these barriers,” said Brittany Birken, a director and principal adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. “And that is something that is relevant to employers and to all of us.”

Birken noted, for example, that a benefits cliff or plateau might mean there isn’t a skilled individual at work when and where you might need them most.

“If there are critical nursing shortages, and there are humans who would be really well positioned in those jobs but who are unable to advance in their careers because there’s a huge financial challenge for them to do so, then that begins to affect us all,” Birken said.

Stakeholders coming together to deal with the benefits cliff and benefits plateau

Some states are addressing the benefits cliff head on. This work has ramped up over the past few years. Public officials, researchers, and Federal Reserve advisers are drawing on the knowledge of people who have encountered a benefits cliff and the many community leaders who have worked with those experiencing such challenges on the ground. Working together, these stakeholders are shedding light on the issue and helping businesses understand why and how the benefits cliff happens.

Anne Kandilis, director of the community coalition Springfield WORKS in Massachusetts, describes her organization’s approach to helping people navigate a benefits cliff this way: “It’s a hand up, not a handout,” she said. “[The people we assist are] working and doing their best. They are hardworking families that are just running in place and not getting ahead. And worse, in times like this, actually falling behind.”

Those working on the benefits cliff issue are also developing tools to identify and address particular cliff effects for individual workers. These tools make it easier for workers to move into the workforce and move up the ladder once they’re in it.

But so far, these efforts are on a small scale and geographically disparate, owing in part to the fragmented nature of public assistance programs. Scaling up these strategies and pursuing policy change at the federal level is a more complex challenge. Addressing the benefits cliff issue and helping those who want to work do so without risking their families’ stability is in the best interest of the US economy overall. As the experiences and challenges in this story will show, shedding light on and understanding the issue are vital first steps. Change depends on bringing impacted individuals together with those who can provide supportive resources, adjust policies, and truly incentivize work for those who want to leave public assistance benefits behind.

Preparing to navigate the cliff ahead

Determined and resilient, Deonne Luacaw returned to work after a personal trauma. Now she worries: Will her family lose the public benefits they need to get by?

Deonne Luacaw in Quincy, Massachusetts. Photo: Steve Osemwenkhae

Deonne Luacaw grew up with few resources and a lot of spirit and determination. Living on her own by 16, Luacaw learned early the value of proactively reaching out to her community for help when she needed it. She graduated high school with the help of community supports, earned a certified nursing assistant qualification, and began working in a hospital. When a personal trauma sidelined Luacaw and forced her to take time to recover, she left the healthcare workforce. Soon after, she had her first child. Luacaw picked up much lower-paying, part-time jobs in retail where she could. Without much income from work, she eventually found herself homeless. Once again, she reached out to local community programs for help.

“My mental health and my kids, those are the only two things that I have,” she said.

Luacaw secured stable housing just south of Boston, Massachusetts. She researched the benefits she needed, applying for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to help her cover her family’s basic needs, and relying on Medicaid for healthcare for herself and her children. A child care voucher enables her son and daughter to go to child care and after-school programs when she works, and a housing voucher helped cover a significant portion of her rent.

Still, Luacaw wanted to find a better-paying, more stable job. She did not want to live on benefits. She wanted to work. With the help of local organizations, she researched jobs with a career path, readied her resume, applied for positions, and prepared for professional interviews. Her efforts paid off: Luacaw is starting a new job as a data clerk for a major health insurance company. Her new role comes with benefits, a career path up the ladder, and a higher income.

When earning more money means less income for budgeting

“I’m finally ready to get back into the workforce full time,” Luacaw said. “This job came along and it’s perfect because they understand that I’m a single mom as well. All my other jobs were customer service and retail, and I was worried about what would happen if there was an emergency at home. So, it’s really good, and I’m really excited about it. They gave me a chance.”

But the higher income is both a blessing and a curse for Luacaw. She now finds herself staring down a benefits cliff even as she celebrates the job she fought hard to get. Because Luacaw and her family have relied on multiple benefits at once, she knows she will face a significant cliff in the coming months with her new income boost.

She is thinking ahead and working with financial coaches from a Boston-area program called Women’s Money Matters to plan out where she may encounter a cliff—or a succession of them—and how she will successfully navigate her way over them.

A key first step for Luacaw will be reviewing her finances with her coach once she gets her first paycheck. “We’re going to write out my goals, how much I can put into savings, when to pay my rent—these are the priorities. Before [Women’s Money Matters], I was never paying my bills on time. Now, I have steps. I have a calendar with reminders, just to anticipate these things. I never had a checking account. They helped me navigate through that. It’s these things that I wasn’t taught. I was just trying to survive.”

She is optimistic that her new job will work out and put her on the road to a much more stable future. But even with her budget navigation plan, she is worried.

Luacaw anticipates her benefits will be cut off soon after she starts the new job. “I’m anxious about it,” she said.

She added, “I live in a high rise, and some of the other women here are on subsidy and fixed incomes as well. I explained to them that I got this job, and they said, ‘Why did you take that job for that much money? You know everything’s going to go up.’ And I’m like, ‘I know, right?’ This is just the common fear, but then on the other side of my mind it’s like, don’t let them bring you down. You’re succeeding. You’re getting out of poverty.”

An uncertain route, especially for families with young children

Brittany Birken of the Atlanta Fed recalled her first encounter with the benefits cliff.

She was the administrator of subsidized child care benefits for the State of Florida when she fielded a call “that forever changed the way I frame the issues around child care affordability,” Birken said. The caller was a parent who told her, “If I’ve done my math correctly, I’m going to lose eligibility,” Birken recalled. The caller’s employer had offered her a 10¢ per hour wage increase, and with that wage increase she was going to lose access to child care subsidy. “She had two children younger than five, so the subsidy value was approximately $9,000 [a year],” Birken explained. “And so, for that approximate $200 annual wage increase, she was going to lose subsidy of $9,000.”

“Families with young children are most likely to experience a cliff that would really create potential financial disincentives from career advancement,” Birken said.

The benefits cliff and benefits plateau affects people in some of the country’s most vital and understaffed industries. For example, people working in the rapidly growing field of social services, such as social workers and early education teachers, are among the most impacted by the issue, said Anne Kandilis of Springfield WORKS, a community empowerment initiative in Springfield, Massachusetts.

If I’ve done my math correctly, I’m going to lose eligibility.

Kandilis described how one partnership yielded unintended benefits. “We had Head Start partners [and] we thought we would be coaching the parents that have children in Head Start. If you qualify for Head Start, you’re one of the lowest poverty families. And we found that the [Head Start] workers actually benefited also, because they were also experiencing the cliff,” Kandilis said.

Randy Albelda, professor emerita of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, has studied benefits programs for 40 years. In one area of this work, she has found that the benefits cliff can be a major concern for home health care workers in their 40s and 50s.

“They may have kids, but their kids are older, so it’s not about the child care subsidy as much,” Albelda said. “Being a home health care aide is one of the more [physically] dangerous occupations,” explained Albelda. “You want your health insurance. A lot of [their employers] aren’t providing health insurance that’s affordable, so you’re not going to want to lose your Medicaid, right? That does you in. The Medicaid cliff is real.”

A benefits cliff can come as a destabilizing surprise

Knowing exactly when and to what degree a benefits cliff or plateau might occur has been notoriously tricky for those encountering them without help.

“In some [benefits] programs you may have to re-determine your eligibility at a three- or six-month cycle,” said Birken. “For others, it’s an annual cycle. Some, like child care, commonly require that you immediately report an income change to make sure you’re still eligible. So, there are different rules for each of these core public benefit programs that families navigate. For some programs, the eligibility threshold is very clear; for others, it may not be as clear to those families. There can be instances where a family might experience a benefits cliff only upon learning that they’re no longer eligible for that public benefit.”

A benefits cliff can wreak havoc on financial and family stability. And it can affect a person’s ability to keep working.

“There are certain types of benefits losses or earnings changes that can cause a fundamental reorganization of your life,” says Michael Carr, associate professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “You might suddenly have to be concerned about whether your employer provides health insurance or not. You might suddenly have to be concerned about what child care location your kid is going to go to or where you can live. You may have to move, and you may have to find new child care arrangements that depend on sources you don’t have to pay, such as parents or neighbors. And you might suddenly find yourself in the private health insurance market.”

When benefits are at stake, it can be hard to persuade impacted individuals to take a chance on a job. They feel a lot of stress around the uncertainty a benefits cliff brings, and danger it can pose to their family’s well-being. Margaret Morton, CEO of Sylacauga Alliance for Family Enhancement (SAFE), a community organization in Alabama, said that people often have been left vulnerable by failed attempts to join the workforce in the past, and so are wary of trying again.

“Just one more time, you promise them the world with a fence around it and it doesn’t happen. [They say,] ‘I just lost everything. I lost my child care, so I can’t go to work. I’ve lost my food,’” Morton explained. “And food security and justice is huge in rural poor Alabama. So [they ask themselves], am I willing to take that leap when actually I’m going to lose in the end and I’m not going to be able to feed my family?”

Just one more time, you promise them the world with a fence around it and it doesn’t happen.

A persistent problem, hard to measure and ‘without a name’

How many people face the benefits cliff? How big of an issue is it, really? It’s surprisingly hard to say, and that’s part of the problem.

There are just not a lot of accurate or representative data on the benefits cliff, said UMass’s Michael Carr, who has spent a lot of time trying to pull together such information. National-level data do not show what’s really happening at the state level, because each state administers public assistance benefits differently. Meanwhile, state-level data can be unavailable to researchers due to privacy restrictions and may be incomplete, depending on how the information is gathered.

Dave Altig, the research director at the Atlanta Fed, explained that this lack of data hurts efforts to address the problem. “It’s so hard to know what the aggregate number of people affected is,” he said, “because across the country, you have to account for all the different rules across all these locations, the differences in the populations, as well as the income profile in each of these different places.

“There’s a lot of information you actually need to get a full picture of this. It’s not going to be very easy to solve the problem in an effective and cost-effective way if you don’t know exactly what you’re dealing with.”

While precise measurement remains elusive, anecdotal evidence points to a significant problem. Professionals in workforce development have long been aware of and concerned about it, according to leaders in the field in states such as Florida, Alabama, and Colorado.

In 2019, the Ohio Chamber of Commerce surveyed its member businesses about benefits cliffs. Almost one in five employers responded that they had seen employees refuse raises or job offers because of cliff concerns. In 2020, a survey of unemployed and underemployed people in Alabama revealed that nearly 38% of respondents turned down a job or promotion due to benefits cliff threats. Earlier this year, a Florida Chamber of Commerce survey found that a third of more than a thousand businesses surveyed said they had experienced employees turning down raises or additional hours.

“For us the issue [of the benefits cliff] has always been around but without a name,” said Dan McGrew, senior vice president for business and workforce strategies at CareerSource, Florida’s state workforce board. “This is that underlying barrier that prevents folks from moving forward, but not explicitly.”

A work requirement that pushed some over the edge

Most of the public assistance programs people use today evolved from programs that were initially designed for single mothers of very young children, according to Randy Albelda of UMass Boston. Women who applied for such benefits were not expected to work, so the phenomenon of a benefits cliff initially was not an issue.

In the 1980s and 1990s, though, federal policymakers made a major change to these benefits, adding a work requirement.

“Many single moms were pushed into the labor market,” Albelda says. “By the early 2000s, it was really clear that people working with low-income mothers were [seeing] this issue of the benefits cliff.”

Low-income parents often end up using more than one benefit program when their children are very young, which means that by the time these parents look to head back into or move up in the workforce, they are facing the loss of multiple benefits at once. Individually, the loss of benefits from a program like SNAP or TANF alone might be a manageable adjustment.

Albelda and Carr have studied what happens when a benefits cliff hits from multiple programs at once. They found that when increases to the out-of-pocket portion someone pays for their housing and child care come at the same time and on top of losing SNAP or TANF, the cliff effect is massive.

Kandilis shared one such story. “I had one woman tell me, ‘I could afford to lose my SNAP, but I couldn’t afford to lose my SNAP with my copays going way up for child care and my rent going up. I couldn’t afford to do all three of those things at the same time.’”

Terms to know

Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF)

aka cash assistance, fka welfare

Might cover a range of needs, including job preparation, work training, and child care.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

aka food stamps

Used to buy food and certain other essentials like diapers.

Backing away from the American dream

Overall, cliff effects vary widely, depending on income, assistance program details, and where in the country a person lives. The size and composition of a person’s family also plays a role in where a cliff might arise for them.

Scott Fast, the director of Colorado projects for Innovate+Educate, said he’s heard understandable concern from people who are staring down those ominous drop-offs. Fast is working with a coalition of government agencies, philanthropic groups, and community organizations in Colorado under an Aspen Institute grant to study and address the benefits cliff.

“People would not even come into the [workforce training] program, which was going to move them up to the target of at least $18 an hour, shooting for $20 to $25 an hour,” said Fast. “Lots of families were saying, ‘I don’t want that job,’ or ‘I can’t afford to take it full time, because I know I’m going to hit a benefits cliff.’”

Fast said people told him they were working harder and getting ahead in their careers, but that their credit card debt was growing. One told him, “I just don’t understand why I’m shooting for the American Dream and it’s not working for me, so I’m going to back away from it.”

Given these realities, some who face the uncertainty of a benefits cliff within the current system find it makes little practical and financial sense for them to work. Experts on the benefits cliff issue note that these individuals are simply acting in their families’ best interests.

I never met a single mom who didn’t want to provide for her kids. It’s not like people don’t want to work.

“I never met a single mom who didn’t want to provide for her kids,” Albelda said. “It’s not like people don’t want to work, but they want to work in ways that work for them, like everybody else.”

When the math doesn’t add up between benefits and work

College student and mom Zuheyry Encarnacion prepares to move off of public assistance benefits over time and save for the future.

Zuheyry Encarnacion in Worcester, Massachusetts. Photo: Steve Osemwenkhae

Zuheyry Encarnacion, following her early interest in criminal justice, enrolled in a Bachelor’s degree program in the subject at Worcester State University in Massachusetts after graduating from high school. Pregnant with her daughter at age 16 and now a busy college student and single mom, Encarnacion uses SNAP and TANF benefits to help her meet her family’s needs while staying on track in school. She lives in subsidized public housing, where she is enrolled in a program that helps working or studying residents manage their budgets, prepare to move off of public assistance benefits over time, and save for the future.

A community program called One Family Scholars covers all of Encarnacion’s tuition and materials costs for school. The program also provides one-on-one coaching and a monthly stipend to help students remain in and finish school.

“I’m really grateful to have One Family on my side and paying off my schooling,” she said. “I feel like that’s honestly the only reason why I’m still in school and still pushing, because if not, I don’t think I would have made it this far.”

As a full-time student, Encarnacion is not required to work to stay in her housing program. Even so, she did work part-time at a restaurant last year for several months. While she was happy to have a job, she quickly discovered it did not pay off for someone in her situation. She faced unpredictable work hours, a difficult work environment, and very low pay. When her small earnings resulted in a dramatic drop in her SNAP benefits, even as her employer reduced her work hours, Encarnacion decided it wasn’t worth the hassle or the risk to her benefits and schoolwork.

“When I was working, my benefits [were] cut down so much that it just made absolutely no sense to keep working,” Encarnacion said. “I would go from, for example, $400 a month to like $50 in [SNAP]. And knowing that groceries are so expensive now, it’s like, what am I supposed to get with this? Not only that, but my rent would go up for working. I was going through instances when Covid was around and my job was cutting my hours [and] my rent would be higher than what I even make.”

Encarnacion is on track to complete school in a year and a half, becoming one of the first people in her family to earn a Bachelor’s degree. She hopes to work with mothers, youth, and families in the justice system once she finishes school.

She has also joined One Family’s Advocacy Team, a group of parents who have experienced the benefits cliff. They support and inform one another and are working on local strategies to address the issue through policy and practice.

“I’ve been through it,” she said. “I’m going through it now. I just feel like I had to be part of something that’s a little bit bigger than myself. Even sharing my story and giving my input, it does help a lot.”

Encarnacion believes having the degree will help her find a stable, higher-paying job. She knows her community program connections will be there to help her, too. Still, she worries about the likely benefits cliff ahead as she transitions from school to work as a single mom.

“I always think, what am I going to do when I really have to get into job mode and I lose my benefits completely?” she said. “Am I going to struggle? Because growing up with my family, my mother was on benefits. I don’t want to struggle, but I don’t want to feel too comfortable on benefits, either. I know I’m going to have to put in the hard work and I know I’m going to have to do what I’ve got to do.”

Navigating very real tradeoffs between benefits and work

Misconceptions and stereotypes abound that people who receive public assistance benefits are looking for handouts, do not want to work, or do not want better jobs.

But in fact, people facing cliff effects are simply doing the math, and that math isn’t adding up.

There’s a misunderstanding that “people are laying out of work or malingering from the workforce,” said Tim McCartney, Chairman of the Alabama Workforce Council. “But what we’re trying to do is get people to understand that [those encountering a benefits cliff or plateau] are actually really smart. They’re looking at that as a tradeoff to say, if I go to work, then I may be losing this much more than I would had I not done that at all.”

“It’s [about] making work pay for people,” McCartney added, “and making sure that the career pathways are dynamic and lead to a family-sustaining wage.”

Talethia Edwards, the executive director of the Hand Up Project in Tallahassee, Florida, is adamant about clarifying this distinction between a perceived lack of effort and the real fear and need for guidance she says families feel as they consider the tradeoffs between benefits and work.

Edwards is the mother of nine children, and she and her husband also experienced the benefits cliff when her kids were young. Her skill at finding creative methods to bridge the cliff and bring in extra money—such as holding bake sales, consigning her children’s outgrown clothing, and couponing—led her to start the Hand Up Project to assist other families going through the same challenges.

Edwards said, “I understand that these are hard decisions that families are making every day—whether or not I’m going to take this position, or I’m going to not work so I can ensure [my family has what we need], because what I can count on is this benefit [coming] every month. What I can’t count on is that this job is going to stay stable.”

I can have an increase in income and not necessarily be stable.

Financial education is also a critical tool for building economic resilience. “I can have an increase in income and not necessarily be stable, right? Because I don’t have the skills to manage it,” Edwards added. “It’s important because it all goes together. Poverty and economic stability, especially for women, it’s multigenerational. There are things that people need—different tools and education—to be able to know what’s next and how to navigate and stay stable and not end up back at square one.”

Eneida Molina in Springfield, Massachusetts reached out for help from community organizations when she experienced the benefits cliff. Now, she works for one of these organizations as a coach and recruiter, helping others like herself. She sees the cliff effect causing stress for her clients at Springfield WORKS as they look ahead in their career planning.

“I really believe people want to work,” she said. “But once the cliff hits, the loss of benefits causes panic. To have relied on benefits and to then suddenly not make enough to afford what was making everything [manageable] not so long ago makes it so much more difficult to focus at work and keep the job.”

Molina’s mentors said she has done well enough to continue to be promoted within the organization. But this career success and higher pay bring new stresses for her. Even as she coaches others, and even with the help she’s received to overcome some of her own benefits cliffs, Molina has a major cliff ahead of her feeding her own worries.

“I am so fortunate to have met all these mentors [who are] helping me to navigate this landscape,” she said. “But even with a solid financial plan, I feel like once again I have to feel all these anxieties once I face that cliff with my public housing. I have yet to hear from [the housing authority], but I know that my rent will go up and that’s where all the anxiety comes in, to see if I can afford all of my bills.”

Employers facing worker shortages are realizing it can be a benefits cliff issue, not a worker issue

Another major challenge of addressing cliff effects is educating employers. Scott Fast of Innovate+Educate in Colorado emphasized that awareness can be a particular challenge for complex businesses hiring workers at a wide range of income levels.

Fast and his coalition colleagues, working with an Aspen Institute grant, have developed an interactive tool to help employers, workers, and others understand where and how a benefits cliff might occur.

“We’ve seen [a benefits cliff impact] with employers that have 10–20% of their workers as blue-collar or entry-level employees,” Fast said. “They design their health benefits and their retirement benefits around their white-collar [workforce], which is way above $25 an hour on average, and design benefits that are unaffordable for their entry level blue-collar workers. We created this toolkit because no employer knew about this [cliff impact]. They only saw it as turnover and people flaking out and people not showing up.”

Frank Robinson knows about the challenges employers face from the benefits cliff. Robinson serves as the Vice President for Public Health at Bay State Health, a health care provider based in Springfield, Massachusetts that employs 12,000 people across four hospitals and the western campus of the University of Massachusetts’s medical school. Many of the organization’s vital, patient-facing employees are impacted by benefits cliffs, Robinson said.

“Cliff effects typically impact our entry level hourly positions,” he said.

“It’s not unusual for a low-wage employee that is making, say, $17 an hour to not be able to advance up the career ladder because a promotion to $20 an hour has the net effect of reducing their overall net income,” Robinson added. “They’re going to lose their child care, and consequently the cost of child care will dwarf the amount of added income they would’ve received from the promotion. So that’s the conundrum for entry-level hourly positions that are looking to move up the career pathway. These workers are largely women that are in a parenting or caregiving role—parenting in particular—and substantially women of color.”

Cliff effects typically impact our entry-level hourly positions.

Robinson said the benefits cliff issue is directly and notably affecting Bay State Health’s ability to grow and expand its services. Talented employees within the organization cannot rise up the ladder without hitting a destabilizing cliff, he said, and some potential new hires can’t get in the door for the same reason.

“It’s frustrating not to be able to advance employees into more attractive positions,” he said. “Employees are frustrated in their inability to move into positions that would allow them to thrive in the sense of their own personal and professional development. And it’s a challenge for the organization that we are not able to fully maximize their talent.”

Could the tight labor market prompt action on a solution to address the cliffs issue?

Despite the cliff effect being a perennial problem, workforce and economic development professionals say there’s greater eagerness now to tackle the issue. As they see it, employers are feeling the strain of the worker shortage, which is one reason they are more likely to come to the table these days.

“We’re in a world right now where employee retention is a very popular topic in the human resources world,” said Dan McGrew of CareerSource Florida. “So, employers are looking for creative compensation—are there ways that we can retain and attract employees? And maybe providing child care subsidies is a way to do that. Maybe providing housing subsidies is a way to do that.”

Across the country in Colorado, Lee Wheeler-Berliner sees a similar dynamic at play.

“We’re in a labor market right now where we cannot afford to have anybody on the sidelines,” said Wheeler-Berliner, managing director of the Colorado Workforce Development Center. “We need every available person capable of working to be actively engaged. So, when we have a segment that is artificially held back because of that fear of losing benefits or their concern about losing some immediate livelihood, that ultimately has detrimental impacts on our ability to keep the economy humming.”

Robinson of Bay State Health said it is certainly in employers’ interest to get involved with creating solutions, especially if their organization depends on entry-level workers growing their skills and advancing up the career ladder.

He offered the example of someone in a lower-paying job such as a medical assistant who wants to move up to the licensed practical nurse (LPN) or registered nurse (RN) level.

“They never could move beyond LPN to RN because they can’t [even] get to LPN because they can’t afford the promotion. And they have all the talent and deep experience and have demonstrated their ability to work successfully in a medical practice and assist providers—they’re now ready for this next step, but they can’t do it because they’ll lose their benefits. Consequently, we continue to struggle to find nurses. The benefits cliff [our employees face] interferes with our workforce development plan and that does reduce our ability to fill positions.”

Similar conundrums arise for lower-income people who would like to move into jobs in other promising fields such as advanced manufacturing and information technology. In part because of cliffs, needed workers are missing in many roles and industries across our economy, slowing business expansion, contributing to shortages in goods and services, and stunting tax revenue growth.

“What makes me most nervous is that we are going to squander the opportunity of a tight labor market to create the momentum to actually solve the problem,” says Altig of the Atlanta Fed. “This is a pretty unusual time, particularly with getting the employer community engaged in the conversation and making them part of the solution. I have some concern that the moment could pass and who knows when it will come back.”

Still, the labor supply squeeze is helping to spur action around this issue that some leading stakeholders have long considered a workforce roadblock, said Tim McCartney of the Alabama Workforce Council.

The benefits cliff interferes with our workforce development plan and that does reduce our ability to fill positions.

“I think the message resonates even more so when there’s a tight labor market and so much friction in the economy due to Covid and other factors,” said McCartney. “That’s allowed us to have a glide path on a lot of issues in this space that maybe were a little avant garde before the pandemic. We were working on it, but it’s so much more in vogue with people at the state and federal levels now.”

Partnering to identify cliffs and traverse them together

Rebecca Flores pulled herself out of homelessness only to walk on the edge of several benefits cliffs. She kept her family on the path to financial stability with help from her employer.

Rebecca Flores in Denver, Colorado. Photo: Ariel Cisneros

Rebecca Flores’s parents worked hard where she grew up in East Los Angeles, CA, but their eventual divorce left her family homeless for a year. After that experience, Flores swore she would never be homeless again. She married, had children, and worked as a teacher in Denver, CO. Although Flores loved her work, she felt she was missing out on time with her kids because of her busy job teaching, so she left the workforce and began homeschooling her children. Then, after 18 years, her relationship and marriage fell apart and she became homeless again, this time with her children.

“My family would of course never want me to be homeless,” Flores said. “But I didn’t even know how to ask them for help. I like to say that because it’s not that I didn’t have any family, it was just more my pride. I didn’t even know I’m digging myself into a deeper hole.”

She and her children experienced homelessness for a few months as Flores reeled from the shock of the change and tried to figure out what to do next.

“I was the one that had the marriage and the kids and the job, and then it was all gone, it felt like overnight,” she said.

That Fall, Flores sent her older kids to school and found a low-paying job at a call center. She applied for SNAP and enrolled in Medicaid to help cover her family’s needs. Though she also applied for a child care voucher to be able to enroll her younger son in child care, she found it did not cover much of the high cost of child care at the centers nearby, where there were also long waiting lists. “I would still have to pay something like $800 [a month],” she said. “I don’t know how people typically do it.” Flores drew instead on the assistance of a family member, whom she paid to help watch her son while she worked.

Flores found ways to stretch her food budget and earn some extra money for her family on the side by donating blood plasma and consigning clothing her children had outgrown. She also took out loans to cover the high costs of electricity and the gas she needed to get to work and drive her kids where they needed to go.

“This position that I had was one of those positions where you kind of just are invisible,” she said. “You go to work, you clock in and clock out, which was what I needed. But then I knew I wouldn’t go anywhere from there. It was very low paying. I thought about going back to teaching, but I knew that that would take me away from my kids. That wasn’t a sacrifice I wanted to make. I just wanted something different now that I was learning more about myself.” Flores heard about and sought help from a local workforce organization, ActivateWork, to try to stabilize her finances. There, she enrolled in a pilot that aimed to help lower-income working people find better jobs while also preparing them for the benefits cliff they would face when they found a higher-paying opportunity. While taking the class, Flores discovered her passion for the work the organization was doing. When they offered her a job, she jumped at the chance.

“I really believed in the work that they were doing for me, and I wanted to kind of pay it forward,” she said.

Her employer was deeply familiar with the danger of the cliff effect. They worked with Flores to keep her initial wages at a level that would not trigger the loss of her benefits right away. With the help of a philanthropic partner, The Bridge Network, and ActivateWork, Flores was able to have the difference between her actual pay rate ($15 an hour) and what ActivateWork would have paid her if they were not concerned about her hitting a benefits cliff immediately ($20 an hour) placed into a deferred savings account in her name. Flores received this cumulative savings amount as a grant when she completed the pilot program after two years.

Her job at ActivateWork came with the chance to build a career, and Flores quickly rose up the ranks. She now works as a recruiter, helping others in situations like hers as they navigate cliff effects. Over time, Flores earned a family-sustaining wage, navigating any benefits cliff that came along through advanced planning and help from her employer. This year, with the money set aside in the deferred savings account, she was able to buy a home for herself and her family.

“It feels wonderful to know that I have money in my savings account, I have money in my home account, I have money in my family account, and I have money to pay all my bills,” Flores said. “This is a moment where no camera can capture the beauty that you feel inside, and knowing that you worked very, very hard. I can’t explain the joy and the actual peace that that hard work has brought.”

Customized tools help communities address the benefits cliff

Flores sought knowledgeable support from a local organization and sustained that partnership in order to navigate her way to financial self-sufficiency. But connecting those who seek that effective, personalized, long-term guidance with the few programs that exist to provide it is a challenge in itself.

The reality is that assistance programs are so complex and varied that solving the problem of the benefits cliff completely will be difficult. Doing so requires a level of coordination, policy attention, data gathering, and cultural shifts that can feel overwhelming.

Addressing the root causes by making changes to the benefits programs themselves at the federal level is a question for Congress. Small-scale strategies that address the benefits cliff may work well on the ground in individual communities or for different groups. Scaling up such strategies to a national level must involve solutions tailored to work for an individual person receiving specific benefits combinations in a particular state and region.

In other words, it’s complicated.

Recently, several states have been experimenting with strategies that promise to make the benefits cliff more predictable and navigable for many workers. So far, these strategies feature a combination of three ingredients: customized and easy-to-use planning tools, the alignment and collaboration of a wide range of community partners around the issue, and the human touch of benefits cliffs navigators. Especially effective as navigators are those who have confronted the issue as public assistance recipients themselves.

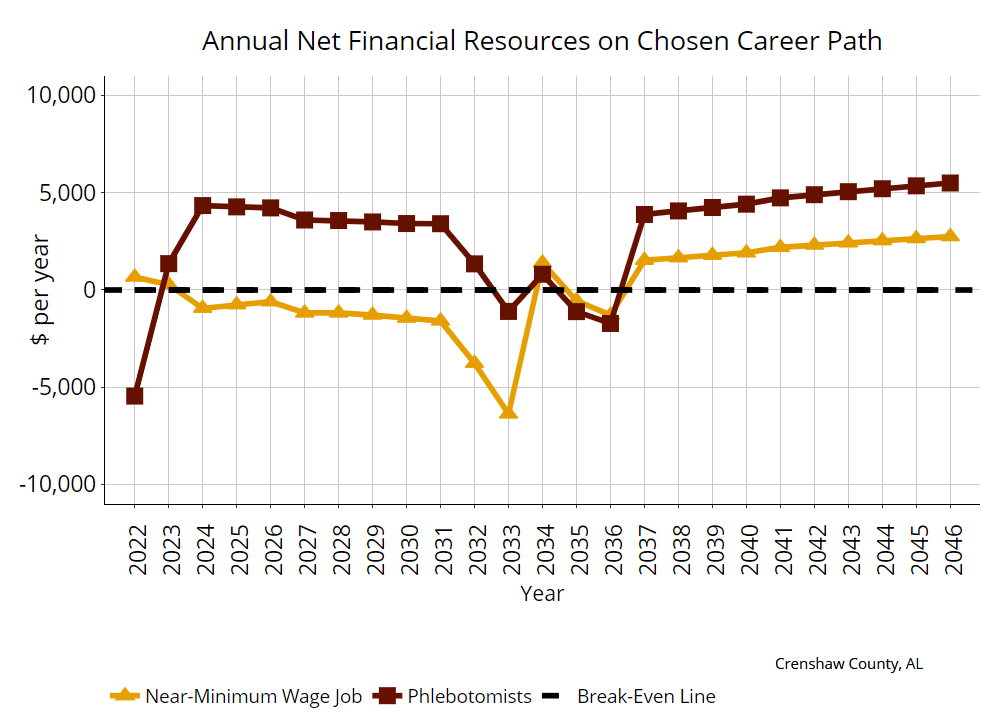

Since 2018, a team of researchers and advisers at the Atlanta Fed have been working on the leading edge of some of these efforts, especially on the development of planning tools. The team has designed, tested, refined, and expanded a suite of interactive tools called the Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster (CLIFF). These tools enable workers, employers, policy makers, and community organizations to explore a range of factors related to the benefits cliff. They draw on databases customized to states, localities, and family structures.

Alex Ruder, a principal advisor and director in the Atlanta Fed’s Community and Economic Development group, co-led development of the CLIFF tools. “There was no tool before it that could answer an important question like, what’s the impact of the benefits cliff on a career pathway over time?” he noted. “There were tools that could tell you the effect of an immediate income change, but no tools could tell you the impact on longer-term plans for career advancement within a company or industry.

“That was an important insight of our work, finding that these [cliff effects] were not just happening in the short term,” Ruder continued. “These losses were causing problems for workers 10, 20 years down the road as they advanced in their careers. When we saw that, we realized this was a powerful tool that needed to be not just for research but also put into practice for people to use.”

Low-income workers can use one tool along with a mentor or coach to plan out where they might encounter benefits cliffs based on where they live, their income, their family structure, which benefits they use, and other elements.

Some people receiving benefits will not yet be ready to enter the workforce. Focusing on introducing the tools to program participants when they are truly in the market for a job is important, said Suzie Miller, workforce programs administrator for Arapahoe/Douglas Works! in Colorado, where the Fed’s CLIFF tools are being used.

“We’ve really started to experiment with where is the most immediate need, and where can these tools be most effective and impactful?” Miller said. “We have a resource center [where] we also have case managers on site that are working with those residents that are on TANF. What we found is that with that population, they weren’t quite ready to dive into the longer-term strategies around the cliff-effect tools that we were using.” So they shifted their focus to SNAP recipients. “We operate the Employment First program, which is essentially the work component of SNAP,” he explained. “We help individuals that are on SNAP search for employment. And we found that this tool was most impactful with some of those customers.”

These losses were causing problems for workers 10, 20 years down the road as they advanced in their careers.

Some states are leveraging CLIFF tools to support both workers and employers

Workforce programs have long been focused on connecting potential workers with the skill sets they need to qualify for better jobs. Lee Wheeler-Berliner of the Colorado Workforce Development Center said that increasing attention around the cliff effect is changing some aspects of effective workforce development strategies. But traditionally there was little focus around the fact that even with those skills, or even when trying to get people to consider training to gain those skills, benefits cliffs and plateaus can foil job seekers’ plans to move into careers.

“A lot of employers expressed the desire to take people who are already employed with that company and equip them with new skills in order to move up and advance,” Wheeler-Berliner said. If those offers were not being accepted, he added, employers weren’t understanding the reasons why.

He noted that the CLIFF tools have enabled workforce professionals at the state level to better explain to employers the reasons behind some of the roadblocks they encounter as they try to fill needed roles.

Colorado Workforce Development Center partnered with the Atlanta and Kansas City Feds to develop the customized dashboard used in Colorado. The dashboard “allows the workforce centers to educate an employer on the different aspects of an employee’s life that they need to be thinking about if they’re going to be offering the highest level of quality within their job opportunities,” Wheeler-Berliner explained.

In addition to Colorado, several other states are partnering with the Atlanta Fed to customize versions of these tools for their communities and weave them into workforce policies and programming at the state level. The tools will be used by direct job-training providers, employers, community development organizations, state agencies, nonprofits, and regional partnerships that include federal agencies.

State leaders appreciate the way that the Atlanta Fed’s customized tools can help them more efficiently direct resources to where they are most needed. “The power of the CLIFF dashboard that we are really excited about is having that information about what will be lost, at what point in time, because then you can lean on your network of providers for wraparound services in a very specific way,” said McGrew of CareerSource Florida. “You’re not just throwing resources at a problem; you’re directing them at a specific point in time.”

In Alabama, the CLIFF tools now are being integrated into the workforce development system across the state, said Tim McCartney of the Alabama Workforce Council. As in Colorado, Alabama’s state leaders have worked with the Atlanta Fed team to design tools that are customized to the state’s needs and goals.

“We built our benefits cliff and self-sufficiency tool, DAVID (Dashboard for Alabamians to Visualize Income Determinations), and we actually require it to be used in our public workforce system for intake for SNAP and TANF, and we’ve cross-trained our entire public workforce system on using it,” McCartney said.

As they move forward with the state’s CLIFF-based workforce infrastructure, Alabama’s team is using their partnership with the Fed to gather more actionable information about the workforce and how to help people successfully get and retain career-track jobs.

For instance, McCartney said, they are using the tools “to figure out who’s in our shadow labor force and how we [can] come up with a way of figuring out who are the people that we can help that would be most amenable to reentering the workforce, and then [also] who are the ones that have a little more complicated barriers to entering the workforce and how we [can] get them what they need.”

Massachusetts exploring policy solutions to benefits cliffs and plateaus

One state is even putting forward for consideration legislation that would pilot a possible mitigation strategy for the benefits cliff issue.

Massachusetts lawmakers have proposed a pilot to study what would happen if families encountering the benefits cliff were able to reduce or eliminate an income shortfall with funding from the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) program. A coalition of community organizations and employers are working with state legislators to design the potential pilot.

Anne Kandilis of Springfield WORKS, which is part of the coalition, explained how the idea would work. “So, let’s say your resources were $53,000 a year. You got a new job, which caused you to lose $10,000 of housing benefits and now your net resources are $45,000. [In the pilot scenario proposed,] your EITC would make up the difference between that $45,000 and $53,000 where you were, and you would get that $8,000 as an EITC. Ideally, we’d also like to pay that out quarterly so you’re smoothing your income with your expenses.”

Massachusetts State Representative Carlos Gonzalez, a co-sponsor of the legislation, said people who haven’t experienced a benefits cliff need to overcome the perception that the EITC is just another handout. Instead, he said, using EITC dollars this way would serve as a short-term investment in people who want to work, likely to lead to a long-term gain for recipients and taxpayers alike.

A program like this turns [a participant] from a tax burden into a taxpayer.

“It’s extremely difficult to try to explain this to other legislators that don’t see the generational poverty that I see in Springfield. It’s not understood,” said Gonzalez. “People understand the purse strings. People understand the wallet. They don’t understand programs.”

He added, “A program like this turns [a participant] from a tax burden into a taxpayer.”

Coaches with personal experience help others navigate the benefits cliff

For those seeing cliff effects on their horizon, one of the most vital and effective supports is a relatable coach who can help walk them through it. Community leaders noted that developing a personalized plan ahead of encountering a benefits cliff is an important start. But they also said it’s easy to get discouraged and overwhelmed anticipating a benefits cliff or plateau because navigating the process can be an emotional roller coaster. Having someone to call when something unexpected happens and the stress level rises helps keep families on track to stability.

“Everything we do is predicated on building a relationship with somebody that we trust. It’s not going into somebody’s office and putting you in front of a computer,” said Margaret Morton of SAFE in Alabama. “The coaching relationship is critical.”

As we’ve seen, understanding where and when benefits cliffs might arise is complicated and confusing. Working with people who have been through what they are facing and who come from their communities can be a welcome support to those navigating job searches and future cliff effects as they develop and move forward with their plans.

Eneida Molina of Springfield WORKS draws on her personal experience to encourage the families she assists to be proactive about preparing for the changes they will see in their benefits as their incomes increase.

“I think that’s what people need,” Molina said. “Not reading something, but hearing it from someone’s voice and their own experience. I think it does help.”

Having made it through encounters with the benefits cliff herself with the assistance of her own community coaches, she’s able to confidently encourage those she works with to persevere with the process.

“Once you go through all the hard work that needs to take place to align the support [you need] before you experience that cliff, you have this feeling of empowerment and achievement,” she tells her clients. “It’s something that no one can take from you.”

Those who have experienced a benefits cliff and now help others navigate them are also jumping in to help address the issue at the system level.

In Tallahassee, Talethia Edwards of The Hand Up Project serves on several committees with organizations like the chamber of commerce to share her grassroots view of what she and her clients have experienced and what she feels needs to change to make the transition from benefits to work more stable and predictable.

Once you go through all the hard work…you have this feeling of empowerment and achievement.

“Overall, the system just needs to think about the end user. It’s not set up for that,” she said.

She believes community organizations focused on the nuances of cliff effects and work transitions play a crucial, unique role in addressing the issue successfully. For one thing, she said, these organizations can provide the time and personalized strategies people need to feel more secure stepping into a job that may lead to a benefits cliff or plateau.

“I get it that the [public benefits administration] system is already burdened, so it’s difficult for systems to hand-hold,” Edwards said. “But I think resourcing small organizations [able to work with clients in] small groups, giving people the chance to feel and be empowered, is necessary and that’s how we get the work done.”

Addressing the benefits cliff offers agency to those seeking a more stable future

Better tools and programs to help people navigate a benefits cliff won’t solve the cliff effect problem on their own. That thornier work calls for changes addressing the deep-rooted causes of the challenges that spur people to seek public assistance benefits in the first place. Still, in the current reality of a benefits cliff or plateau causing people to think twice about taking a new or better job, these tools and programs play a vital role.

Without them, people facing a benefits cliff basically have two choices: take the job or pay raise and risk losing benefits before they can afford to, or reject the job or pay raise and, with it, a potential career path and more financially stable future.

Tools and programs like those described here introduce a third choice. People can take the job with guidance and resources that are more likely to help them traverse a benefits cliff or plateau instead of getting derailed by either.

Taking things one step, and one win, at a time

Financial uncertainty is a difficult constant these days. And one benefits cliff avoided or successfully navigated might be followed by another. But the added financial, social, and motivational support seem to make a successful journey across benefits cliffs a lot more likely for people like the women featured in this story.

Now that they have navigated some of the processes around benefits cliffs, Deonne Luacaw and Rebecca Flores are excited for what lies ahead. While they may still encounter more cliff situations in their future as they continue to grow in their careers, each woman has renewed confidence that she can make it through.

As she starts her new job, Luacaw feels encouraged by her children, who have noticed that her hard work is paying off.

“It’s really rewarding just to see the smile on my kids’ faces every morning,” she said with her own smile. “I used to just get up and bring them to school in my pajamas. Now I get up and I do my hair, and they’re like, ‘Are you going to work on the computer?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah.’ They’re so proud of me. My kids are very proud of me. I’m really looking forward to being self-sufficient and finally trying to get off of these supports. It’s really a good feeling.”

Flores is enjoying the new home she was able to purchase thanks to her deferred savings. She takes to heart that she’s able to show her kids the fruits of her labor and planning, and that she will now be able to give them a better life.

“My kids will not ever have to live in a car again,” she said. “My kids will not ever have to know what it’s like to not pay a bill so you can rob Peter to pay Paul. They never need to know what it’s like to not have money to pay for something that’s important like food or clothing, or to have to say that I couldn’t get the shoes that were $10 because it’s either that or gas. They don’t have to experience that because of the mentors and the people that were in place to help me unlearn finances and relearn better in my financial walk.”

Flores is proud of how far she’s come, she said, and that she’s achieved a level of stability that brings her some peace after years of anxiety.

“I’ve gone from sitting in my car one day thinking, I don’t even know how I’m going to do it, I just know I have to make it happen somehow, all the way to coming to sitting outside my new home looking at my kids playing. I haven’t arrived, there’s still a lot to do, but I definitely am going to take this win.”

Additional sources

Community and Economic Development Director and Principal Advisor

Atlanta Fed

Tallahassee, FL

Associate Professor, Department of Economics

University of Massachusetts, Boston

Boston, MA

Representative, 10th Hampden District

Massachusetts House of Representatives

Boston, MA

Director, Springfield WORKS

Western Massachusetts Economic Development Council

Springfield, MA

Senior Vice President, Business and Workforce Strategies

CareerSource Florida

Tallahassee, FL

Community Alignment Specialist

Western Massachusetts Economic Development Council

Springfield, MA

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people for contributing their time and expertise to this series.

Marija Bingulac

Community Development Manager

Boston Fed

Ariel Cisneros

Senior Advisor

Kansas City Fed

Colleen Dawicki

Deputy Director, Working Places

Boston Fed

Barbara Dwyer

Assistant to Dave Altig

Atlanta Fed

Diane Fisher

Administrative Assistant

Baystate Health

John Gilchrist

Policy Analyst

Alabama Governor’s Office

Julie Kornegay

Engagement Liaison

Atlanta Fed

Brad Kramer

Director of Public Policy

One Family, Inc.

Karen Leone de Nie

Vice President

Atlanta Fed

David McNeill

Chief of Staff,

Representative Carlos Gonzalez

Massachusetts State Legislature

Danielle Piskadlo

Executive Director

Women’s Money Matters

Steven Shepelwich

Lead Community Development Advisor

Kansas City Fed

Andy Zajac

Executive Communications Writer

Cleveland Fed