Brandon Kelso lived with his father and sister in a modest Columbus, Ohio house when his father passed away in 2017. Kelso, then 28 years old, negotiated a new contract in 2020 with the home’s seller to take over the monthly payments his father had been making since 2012 to purchase the house. Kelso continued paying each month with the understanding that at the end of the contract term, he would own the home.

But after Kelso submitted his final payment in July 2023, the seller didn’t transfer the deed proving Kelso’s ownership of the home. Kelso repeatedly asked for the deed as agreed to in the contract but got no reply. Instead, the seller offered Kelso $200 to leave the home, which he declined. An eviction notice on Kelso’s door followed.

That’s when the police arrived, and Kelso learned the seller had reported that he was breaking and entering.

“How is it breaking and entering if it’s my house and I have the keys?” Kelso recalled thinking.

If you bought your home with a mortgage that you pay down each month, Kelso’s experience might sound like a horror story. How can you lose a home you’ve spent years paying for just like that? But Kelso didn’t have a mortgage. He was paying for his home through a purchase agreement known as a contract for deed (CFD).

CFDs can appeal to lower-priced homebuyers who believe they are unable to qualify for or secure a mortgage. CFDs typically lack the consumer protections that come with mortgages, though, and include clauses that can cost unsuspecting buyers their home and their investment in it. Based on their study of such arrangements, the National Consumer Law Center estimates that more than 50 percent of CFDs fail.

“These sellers are selling the concept of homeownership but not the reality of it,” said Patrick Skilliter, manager of the economic justice team at Legal Aid of Southeast and Central Ohio, who handled Kelso’s case.

How contracts for deeds work

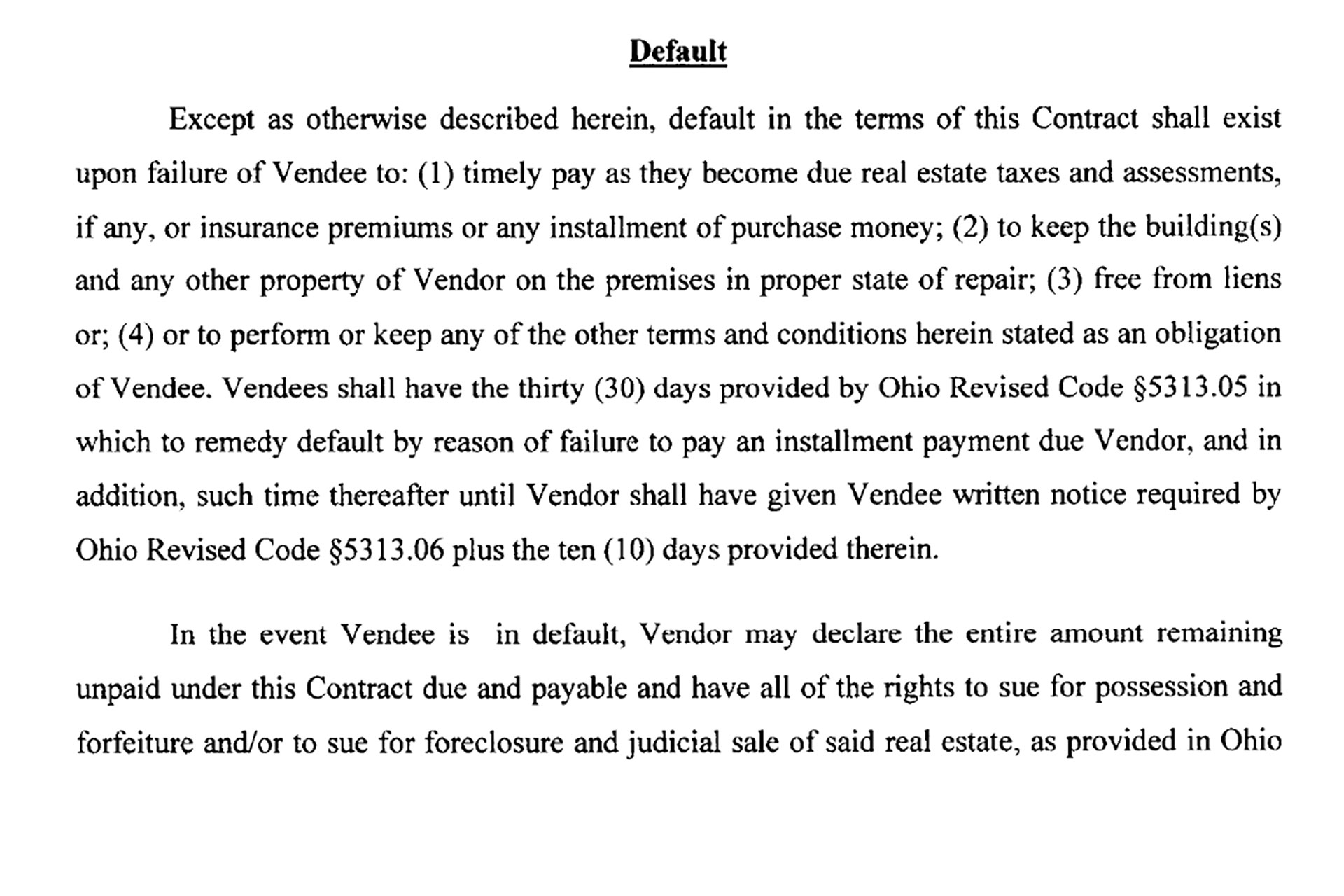

In a CFD—also called a land contract or agreement for deed, among other names—a buyer agrees to certain terms and a payment schedule to pay a seller over time for a home. Once the buyer completes all payments, the seller conveys the home’s deed to the buyer. CFD sellers range from investment companies with large portfolios of CFD-financed homes to individuals with just a few local properties.

Buyers may use a CFD to finance their home purchases for many reasons. Not everyone who wants a mortgage can qualify for or get one. For example, lenders may deny mortgage loan applications from prospective borrowers with damaged or lacking credit histories. When buying a lower-priced home, it may be hard to find a lender willing to grant a small-dollar mortgage loan. Buyers in these situations could find a CFD offer attractive.

In other cases, a home goes into foreclosure after the owner falls behind on the mortgage payments. The home’s new purchaser may then turn around and offer the home to the original buyer, but under a CFD agreement. The original buyer may jump at the chance to regain ownership and stay put.

Enlarge image.

Challenging to quantify the full reach of the problem

It’s difficult to know for certain how many buyers nationwide are making payments under a CFD. Many states don’t require that CFD sellers record the contract with any local records office. Even when contracts are recorded, missing information can obscure whether an arrangement really is a CFD. Buyers surveyed for research may not know they are under a CFD or mistakenly may think they are.

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland and Atlanta have identified almost 500,000 instances of CFDs between 2005 and 2022 in available records across the country. Their research, publishing soon, looks at whether these contracts succeed or fail. For Fed researchers, studying CFDs links back to economic mobility.

“Homeownership is one way to move up the economic ladder,” said Lisa Nelson, an assistant vice president for community development at the Cleveland Fed. “So, we want to know whether CFDs could be a pathway to homeownership for those who don’t qualify for or don’t want a mortgage. Are they really, or are they not?”

The majority of CFDs may be missing from public records, though. According to researchers, some legal practitioners believe three-quarters to four-fifths of all CFD agreements aren’t recorded, and therefore aren’t in available data.

Disproportionate contract for deed harms

Where data exist, recent studies show concentrations of CFDs in the Midwest, especially in Michigan and Ohio. Following the Great Recession of 2008, researchers noted an uptick in CFDs in communities heaviest hit by foreclosures and damage to consumer credit.

CFDs appear more often in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of people of color and lower-income households. In a 2020 Federal Reserve study, for example, 63 percent of identified CFDs were concentrated in areas with a lower median household income ($37,115 versus $51,353 overall) and a higher percentage of Black households (7.2 percent versus 3.7 percent overall).

CFDs appear more often in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of people of color and lower-income households.

The National Consumer Law Center interviewed CFD case attorneys in 2016, learning that the majority of their clients were Black or Latino homebuyers. These attorneys reported CFD marketing targeted specifically toward Black and Spanish-speaking communities.

What can make a contract for deed agreement risky

CFDs can be risky arrangements that too often leave buyers worse off than they were when they signed the contracts. The attorneys and researchers interviewed for this article said they could see few scenarios in which typical CFDs might help buyers enter stable homeownership.

A small number of mission-driven nonprofit organizations have achieved better outcomes using contracts that include more of the consumer protections missing from typical CFDs. But these cases are the exception to the rule.

“I think land contracts are inherently unsafe because of the way they realistically play out,” said Skilliter at Legal Aid.

A CFD might seem like a reasonable option for aspiring buyers unable to access more traditional home-purchase financing. But these buyers may not know the risky terms that come with the contract they’ve signed.

Historically, CFDs haven’t been covered by many national lending laws that protect consumers. State protections vary widely. Many don’t require that CFDs be filed with a city or county records office. In some cases, sellers may not even provide the buyer with a copy of the contract. If an unrecorded CFD ends up in dispute, buyers have no official record of the agreement to back them up.

“It’s buyer disadvantage. Anecdotally, we’ve heard that some sellers literally had ‘mortgage’ written on the top of the contract, and it wasn’t a mortgage.”

– Lisa Nelson, assistant vice president for community development, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

“It’s buyer disadvantage,” said the Cleveland Fed’s Nelson. “Anecdotally, we’ve heard that some sellers literally had ‘mortgage’ written on the top of the contract, and it wasn’t a mortgage.”

Typically, homes offered under CFD haven’t been appraised or inspected. Though they don’t yet own the homes, buyers often must pay property taxes and cover home-repair costs under these contracts.

“A land contract can be a pretty sweet deal for a seller,” said Jacqueline Gutter, an attorney at Legal Aid of Southeast and Central Ohio. “They don’t have to do all the normal landlord duties, but they can get their property taxes, improvements, and rental income covered by the buyer.”

CFD evictions create a continuously churning sales cycle

Under some contracts, buyers nearing the end of the agreement may suddenly face much larger monthly payments. These balloon payments make buyers in many states particularly vulnerable to losing years of investment along with their homes if they miss a payment, even so late in the contract term.

That’s because CFDs commonly include a forfeiture clause. If a CFD buyer misses just one payment, the seller can evict them immediately. Evicted CFD buyers usually can’t recover previous payments, even if they’ve been paying diligently for years. This is particularly true if they have no record of those payments.

“This is a cycle,” said Skilliter. “When a seller evicts someone, that property is going to be back up for sale on land contract for the next person to come along and buy it. And that’s just going to keep happening.”

CFDs commonly include a forfeiture clause. If a CFD buyer misses just one payment, the seller can evict them immediately. Evicted CFD buyers usually can’t recover previous payments, even if they’ve been paying diligently for years.

Some CFD buyers may be ineligible for foreclosure protections. Others, facing an eviction threat, may assume they have no recourse. Even in states like Ohio, which has some CFD protections, including a recording requirement, buyers may only find help after they are summoned to eviction court.

“The scary thing with this is, there are statutes,” said Legal Aid’s Gutter. “The law states that sellers have to record contracts. It’s just that a lot of times they don’t. For mortgages, we have a ton of rules. I think the consequences for land contract sellers have to be more serious.”

With so few protections and so many risks, CFDs are much more likely to unravel to the buyer’s harm than a traditional mortgage. One study of CFDs in Texas found that just 20 percent of buyers under a CFD agreement received title ownership of their homes after eight-to-10-year terms.

“When we think about the mortgage space, we think about a one percent annual foreclosure rate as being a really big problem,” said Hal Martin, a Cleveland Fed policy economist. “We’re looking at multiples of that for the people who aren’t succeeding in CFDs.”

“When we think about the mortgage space, we think about a one percent annual foreclosure rate as being a really big problem. We’re looking at multiples of that for the people who aren’t succeeding in CFDs.”

– Hal Martin, policy economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Increasing consumer protections around CFDs

Despite the well-documented risks of CFDs, these technically legal agreements keep appearing. Given this reality, many researchers, policymakers, and legal professionals believe some measures could help protect consumers from greater harm.

Outreach by trusted community organizations and legal aid offices can raise awareness about what CFDs are and how to spot such arrangements before signing them. Even if a buyer decides to go ahead with a CFD, this advance information helps the purchaser know what to look for in the contract and recording process.

Ensuring that sellers properly record contracts and that both parties keep documentation of payments are important protective steps for buyers. CFD sellers and buyers typically sign the contract with no other professionals involved, posing a vulnerability for buyers.

“Traditional mortgages come with a higher bar of consumer protections,” said Sarah Stein, community and economic development (CED) adviser at the Atlanta Fed. “The reality of CFD transaction is that there often have been no Truth in Lending Act (TILA) disclosures or review of a borrower’s ability to pay, even when there should be. There is seldom a licensed professional like an attorney conducting the transaction. If someone is a first-time home purchaser, how would they know what to expect?”

“There is seldom a licensed professional like an attorney conducting the transaction. If someone is a first-time home purchaser, how would they know what to expect?”

– Sarah Stein, CED adviser, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Skilliter noted that including lawyers, local auditors, and/or realtors on the front end of the contract review process could help buyers identify and better understand CFDs’ risks.

Nationally, policymakers have raised concerns about CFDs and proposed regulations to strengthen buyer protections. Senators Tina Smith of Minnesota and Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming introduced a bill in February 2024 that would require sellers to record contracts. It would also mandate using the more buyer-friendly foreclosure process instead of proceeding with eviction if a buyer misses payments.

In August, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau released an advisory opinion stating that some CFDs are covered under TILA. The applicable requirements include determining that borrowers have a reasonable ability to repay the loan, disclosing payment schedules and interest rates, and limiting balloon payments.

A year’s legal fight for a deed in hand

Homeowners like Brandon Kelso know the risks of a mishandled CFD all too well. It took Kelso and Skilliter a year to resolve Kelso’s case in court.

Kelso finally received the deed confirming his title ownership of his Columbus home in July. “I feel like a homeowner now,” he said. “It’s a big deal, because my sister and I don’t have to go anywhere. It’s our house, bought and paid.”

Kelso said he would advise other buyers in CFD situations to be sure they keep documentation of their payments and reach out to legal professionals before they walk away from their homes. “Stay calm,” he said, “and make sure you have all the information. Because the seller doesn’t want to help you out. They want to put you out.”