The Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) have been working to strengthen and modernize regulations implementing the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). This joint effort reflects the first significant modernization of the CRA in about a quarter century.

Let’s take a look back at the CRA’s past, including the historical conditions in the nation that inspired it and shaped its implementation.

A government-sponsored corporation and federal housing agencies are formed to support homeownership…for white people.

For most of the 20th century, federal initiatives subsidizing homeownership excluded Native American households and households of color. From 1934 to 1962, for example, 98 percent of federally backed home loans from one program went to white homeowners.

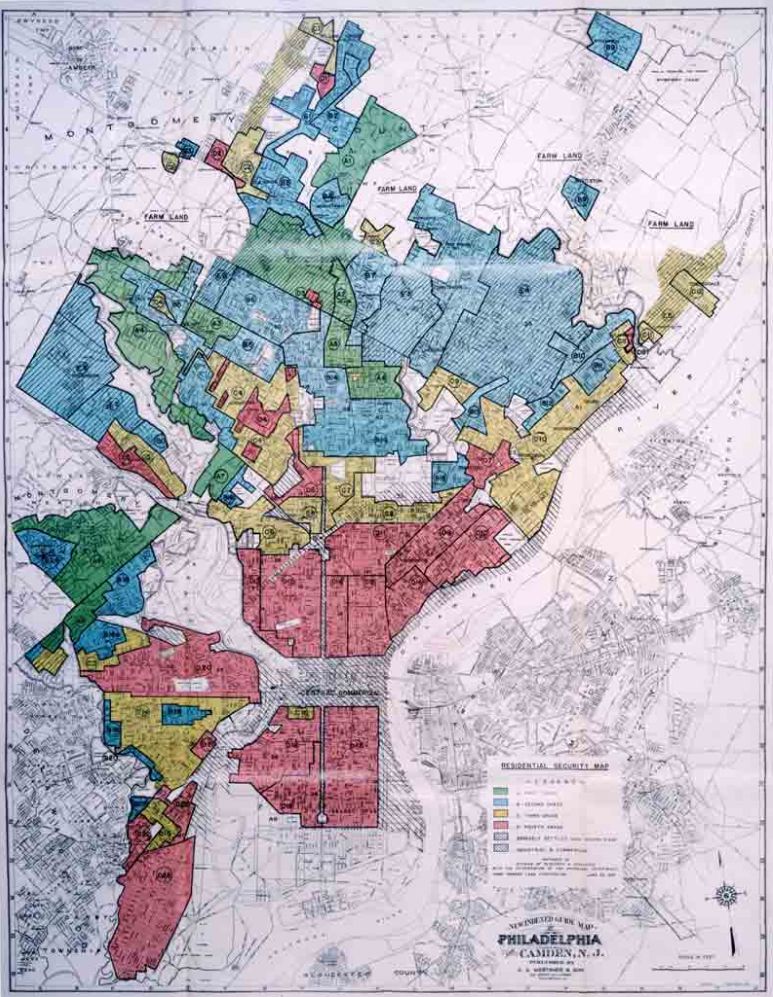

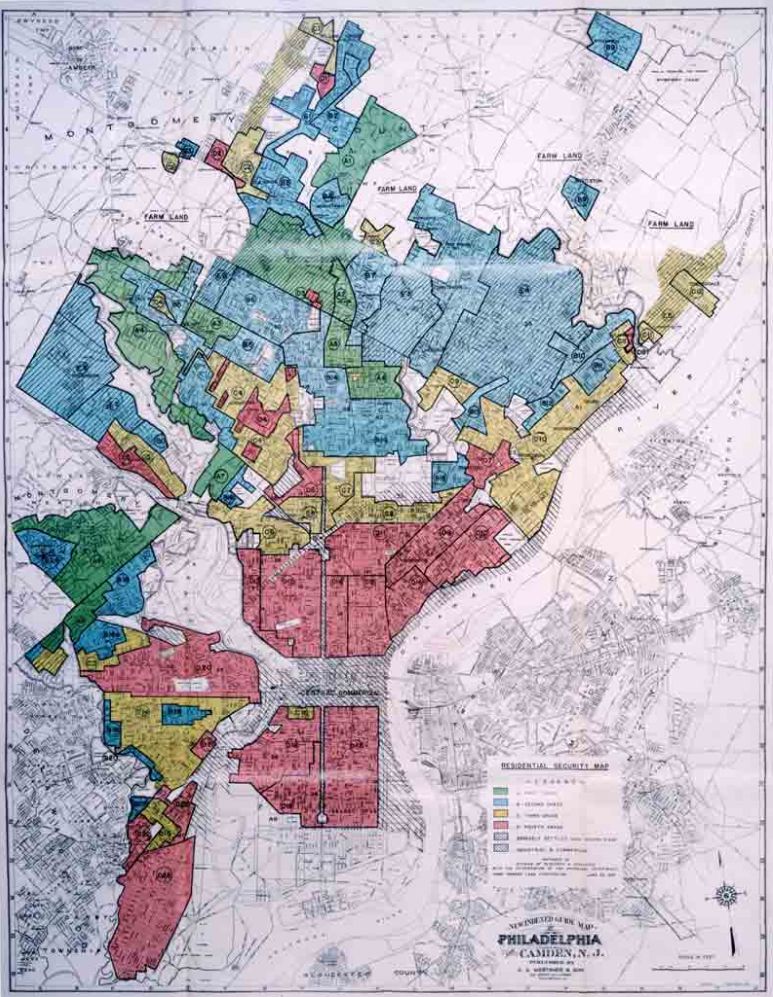

Homeownership programs often relied on maps that color-coded neighborhoods across the nation based on their perceived riskiness for lending.

The neighborhoods described as high risk were “redlined.” But the maps’ definition of risk was defined by prejudice, not just actual creditworthiness. Applicants’ nations of origin, their skin color, and other irrelevant characteristics were also factored in.

Redlining caused more enduring harm than limiting people’s opportunities to buy a house or finance a business.

Federal Reserve researchers have credibly linked redlining to long-term impacts. Redlined neighborhoods are more likely to negatively influence their residents on labor market outcomes, incarceration, and credit scores. People living in these neighborhoods are also less likely to own a home and more likely to experience racial segregation. Redlining’s legacy is even correlated with higher COVID-19 infection rates.

Legislation hints at the intersection of community development and banking regulation.

In 1956, Congress passed the Bank Holding Company Act. As a result, banks or bank holding companies would need to demonstrate their responsiveness to community needs before the Federal Reserve would approve consolidation with other financial institutions.

Supportive policymakers devised the legislation in part because of a concern that larger banks, or bank chains, could replace local institutions without adequately providing for the continuation of services to local communities.

Without this regulation, banks could also use bank holding companies to pursue lines of business that could threaten the stability of the banking sector.

The federal government begins its attempts to end discrimination in lending and housing.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order making it unlawful for federal agencies to allow or promote racial discrimination within housing assistance programs.

Photo credit: Robert Knudsen. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Congress enacts Fair Lending Laws.

A series of fair lending laws was passed, including the Fair Housing Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act. These prohibited certain racial, gender, and other forms of discrimination in residential real estate, banking services, and credit transactions. For the first time, Congress would also require lenders to track data on mortgage loans.

Photo credit: Fair housing protest in Seattle, Washington, 1964. Jmabel/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-ND

Ultimately, these laws would not eliminate racism or unfair lending practices.

Their enactment did, however, give regulators some new tools. They could now identify and sanction some of the worst manifestations of discrimination in lenders’ providing access to capital.

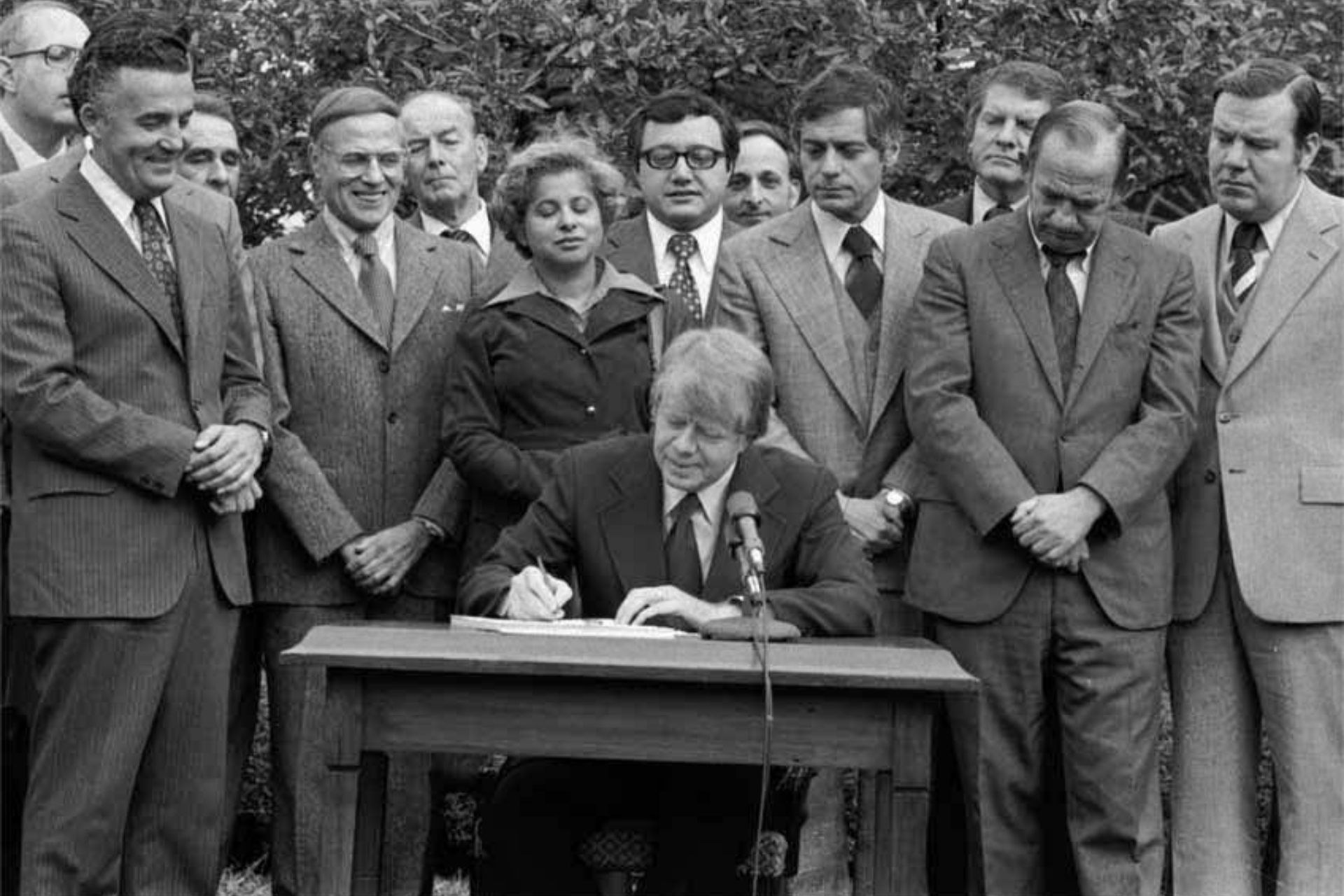

1977

The Community Reinvestment Act is passed to encourage the sound provision of lending, financial services, and other investments in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

Community advocates, policymakers, and economists argued that people in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods still struggled to access credit despite the fair lending laws. In service of this assertion, Congress designed the CRA to evaluate banks’ efforts to meet the credit needs of all people in their communities.

The CRA would not require banks to take undue risks to serve anyone.

Regulators would develop criteria for exams that would assess whether lenders’ processes for extending credit excluded any neighborhoods in their market.

Some of these initial criteria are still in use today. Over time, CRA exams would change, as would activities the Fed undertook to encourage relationships between lenders and community organizations.

Photo credit: President Carter signing the Community Reinvestment Act on Oct. 12, 1977. (Jimmy Carter Library/National Archives and Records Administration)

The Fed builds on its role in the community development sector…

The 1980s saw the CRA receive tweaks to improve upon its initial implementation. For example, the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors asked each of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks to create a community affairs function.

Today, operating under the Community Development moniker, these regional departments within the central bank share a common focus on building relationships between community groups and lenders.

Community Development teams across the United States conduct research, convene events, and continue to build awareness of the CRA’s potential for helping banks in their regions to support credit-access opportunities in low- and moderate-income communities.

…and the CRA is redefined.

Changes in the 1980s also introduced the rating scale used in today’s CRA exams. Further, banks were now required to make available to the public the results of their CRA evaluations.

The CRA is updated to reflect trends in the public and financial sectors.

New legislation passed in the 1990s aimed to incorporate public and industry feedback about the CRA evaluations’ consistency and relevancy.

Notably, these reforms raised the stakes for CRA exams, tying a bank’s ability to expand its holdings, primarily through acquiring other financial institutions, to its previous CRA performance.

Regulators update guidelines.

The Fed, OCC, and FDIC devised new guidelines that responded to consumers’ concerns and changes in the banking industry since the CRA’s passage into law in 1977. For example, revamped examination processes would better differentiate between banks of different sizes. The new processes also clarified the expectations for banks’ community development work and addressed concerns about the cost of compliance.

Changes to the CRA also reflected a longer-term policy trend since the CRA’s passage.

Increasingly, federal resources devoted to lower-income neighborhoods involved private-sector investments. Changes made to the CRA encouraged banks to increase their investments in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods through public–private partnerships.

For instance, banks were recognized for employing new tools such as the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) and the New Markets Tax Credit. The CRA changes also encouraged banks to partner with community development financial institutions (CDFIs).

Evidence grows for the CRA’s efficacy as the Great Recession brings new critics.

Attempting to prove the impact of a single piece of legislation or regulation on the nation’s financial system can be like looking for a needle in a haystack. Did a bank expand its activity in a low-income neighborhood because of the CRA, because such activity was profitable, or for some other reason or reasons?

Several economists turned their attention to these difficult questions in the 2000s. Most used empirical data to argue that the CRA appeared to increase mortgage lending in LMI communities, but not everyone agreed.

The CRA’s flexibility contributed in some ways to the debate. Since the regulation is not explicitly prescriptive, it can be difficult to disentangle the impact of the CRA from other influences on lenders’ behavior.

Later in the decade, questions arose about the CRA’s potential connection to the 2007–2009 recession.

That recession was caused in part by a wave of delinquencies in the mortgage market. Some argued that the CRA was tied to the crisis because it encouraged banks to lend in LMI communities. There is little data to support this claim.

For example, very few of the subprime loans blamed for the recession were made by CRA-covered lenders in CRA-eligible neighborhoods or to LMI borrowers. Plus, CRA-relevant loans actually had lower default rates than mortgage loans overall.

Banks and regulators build on the CRA’s legacy.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the Fed focused some of its research and outreach on the foreclosure crisis. Other Fed efforts highlighted the potential for the CRA to support child care, health, broadband, and more.

The three agencies implementing the CRA continued to provide guidance on how banks could receive CRA consideration for community development activities in the Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment publication.

A new era of CRA modernization begins.

On October 24, 2023, the Fed, FDIC, and OCC jointly issued a final rule to strengthen and modernize regulations implementing the Community Reinvestment Act to better achieve the purposes of the law.

The final rule represents the most significant revisions to the CRA in more than 25 years. The agencies focused on adapting the CRA evaluation process to reflect changes in the banking industry, including mobile and online banking, and to provide greater consistency and transparency for lenders and the public.

Views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

This post originally published on January 28, 2022. It was last updated October 26, 2023, to include information about the Federal Reserve Board’s, OCC’s, and FDIC’s interagency efforts to strengthen and modernize Community Reinvestment Act regulations.