Worker Voices Special Brief: Barriers to Employment

By Sergio Galeano, John Rees, Elizabeth Bogue Simpson

November 15, 2023

The Worker Voices Project, a Federal Reserve System research study launched in 2022, aims to elevate the experiences of workers without four-year degrees during the COVID-19 pandemic (Miller et al. 2023). Through 19 focus groups with workers and job seekers conducted from May 2022 through September 2022, the study provides a nuanced understanding of worker experiences during a period of rapidly evolving labor market dynamics. This brief analyzes transcripts from these focus groups and data from a participant survey to provide insights on the barriers to employment participants experienced during this period.

Introduction

The global pandemic and its aftermath represented a period of significant economic turbulence. In April 2020, the unemployment rate approached 15 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics n.d.b.). By the time these focus groups were conducted, however, the unemployment rate was below four percent and there were more than 11 million job openings nationally (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics n.d.b.; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “JOLTS – May 2022”). While these conditions might typically create a favorable labor market for workers, particularly those with lower labor force attachment, the experiences of participants in our study often told a different story (Bergman, Matsa, and Weber 2022).

Our focus group participants reported that during this period, barriers to employment were common. Both employed and unemployed individuals in the focus groups faced a wide set of barriers to securing and maintaining employment. Further, workers in low- and mid-wage roles were more likely to be laid off during the pandemic (Bateman and Ross 2021). The pandemic and resulting economic disruption worsened barriers that predated the pandemic, such as the difficulty accessing affordable childcare (Igielnik 2021). The pandemic also created new challenges for workers in low-wage roles, such as increased health risks for contracting COVID, and for non-degreed workers, such as the inability to participate in remote work (Kinder and Ross 2020; Daly, Buckman, and Seitelman 2020). Inflation, which disproportionately affects low-income workers and households, was also elevated during the period in which our focus groups were conducted (Jayashankar and Murphy 2023; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics n.d.a).

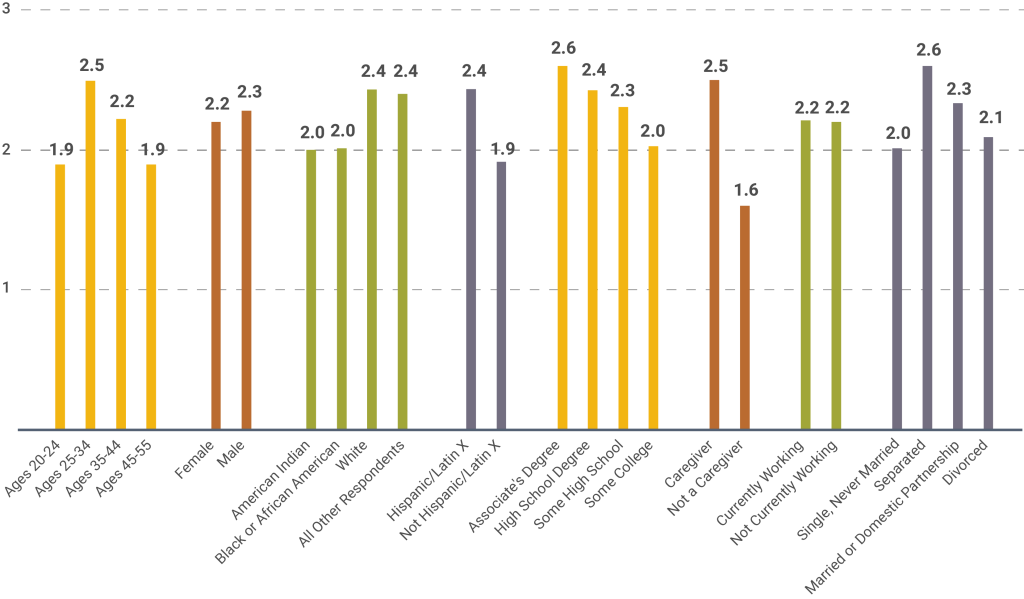

In a survey administered prior to focus group sessions, participants were asked to identify if they had personally experienced one or more of 12 barriers to employment. These barriers include issues such as homelessness, citizenship status, or a lack of adequate skills to successfully compete in the job market, among others. On average, focus group participants reported personally experiencing around two to two and a half barriers to employment. The average varied only slightly across various demographic groups, including age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, caregiver status, employment status, and marital status (Figure 1). Participants also noted the compounding impact of experiencing multiple, sometimes intersecting barriers that prevented them from finding or sustaining employment.

Figure 1. Average Number of Barriers to Employment Cited by Participants in Pre-focus Group Survey

NOTES

Participants were asked to select from the following barriers to employment they personally experienced:

Affordable Childcare

Available Childcare

Citizenship Status

COVID-19

Criminal Convictions

Disability

Homelessness

Lack of Skills

Language Barriers

Mental Health Challenges

Substance Abuse

Transportation

The barriers to employment that participants described generally fell into one of four following categories:

- Job Requirements and an Evolving Labor Market—Educational requirements and an evolving labor market made it difficult for participants to find and maintain stable employment.

- Worker Attributes and Personal Histories—Participants frequently cited individual circumstances such as disability, age, and immigration status as employment barriers.

- Work-Family Conflicts—Many participants reported struggling to balance caregiving responsibilities and the need to protect the health of family members with the demands of work.

- Individual Well-Being—Participants identified physical and mental health challenges that interfered with their ability to maintain employment.

Each of these categories is detailed in this brief. Participants’ insights reveal the complex challenges that individuals without a four-year degree faced as they navigated the job market during a global pandemic. Collectively, these insights also demonstrate how direct engagement with workers and job seekers can provide a more nuanced understanding of labor market dynamics for policymakers aiming to increase economic mobility and resilience for lower-income workers (Miller et al. 2023).

Job requirements and an evolving labor market

It’s like you need a bachelor’s degree to do literally anything, which I think is a little unfair, because there are definitely jobs I could do that I would not need bachelor’s degree for.

-Worker Voices participant

Educational barriers

Not holding a bachelor’s degree is a common barrier to both employment and finding a higher quality job that provides upward mobility (Abel, Florida, and Gabe 2018). On average, workers without bachelor’s degrees earn less over their lifetimes compared to workers with bachelor’s degrees (Carnevale, Cheah, and Wenzinger 2021). Nationally, there are significant disparities in educational attainment across race and ethnicity. Twenty-eight percent of African Americans and 21 percent of Latinos held at least a bachelor’s degree in 2022, compared to 42 percent of white Americans (U.S. Census Bureau 2023). Workers without bachelor’s degrees also face higher unemployment rates compared to workers with bachelor’s degrees, a challenge supported by the experiences of several participants (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics n.d.c.).

“I realized that they started by removing those who didn’t have a four-year college degree. They selected the first person and started removing.”

“Since I didn’t really have much skills and I wasn’t, you know, a college graduate, I was laid off after my first paycheck.”

Requirements

In response to pandemic-induced labor shortages that arose across many roles and industries, some employers began to place less emphasis on formal educational attainment among prospective workers and removed degree requirements from job descriptions (Ferguson 2023; The Burning Glass Institute 2022). Despite the trend towards reduced educational requirements, however, several participants in our focus groups still reported difficulty in finding employment. In their experience, the lack of a college degree remained a disadvantage. Several reported they were often competing for jobs against applicants with post-secondary credentials.

“[E]veryone wants a degree. Even though I have 10 years in warehouse management, that should be [sufficient] enough for it.”

“[M]ost of these people are like, fresh out of college with degrees, and they can’t even find work.”

Several participants in the study also cited a greater amount of required skills as barrier to finding employment.

“There seems to be like this huge gap between the jobs that are available and the jobs that people are looking for. It seems that the requirements that are being asked for are a lot higher requirements than [the skills and degrees of] those who are seeking the job openings.”

“A lot of jobs started asking for more requirements. [It changed from] ‘we just want to know if you can do these simple coding languages’ to ‘you need to have four years of experience’.”

In order to recruit from a wider talent pool, some employers have adopted fair chance hiring policies, stating they would not discriminate against applicants with criminal records (Konkel 2022). Despite experiencing a labor market and job search process that felt more forgiving of their past, however, one participant noted that many jobs for which they applied came with lower pay yet more job responsibilities.

“People kind of have eased up on that part [criminal records]…but they’ll change the title and lower the pay.…It could be the same administrative position they offered last year, it’s just lowered by $2 [per hour].”

Job search barriers

Some participants reported lengthy job search and application processes that yielded few leads and little potential. Repeated rejection contributed to a sense of discouragement. Additionally, the pandemic accelerated the adoption of new technology (LaBerge et al. 2020). An analysis of 2022 job postings found that 92 percent of jobs require digital skills, putting workers with lower digital literacy at a disadvantage (Bergson-Shilcock, Taylor, and Hodge 2023). This lower digital literacy also affected participants’ ability to search for a job using online platforms like LinkedIn.

“[T]here’s new things you have to use now like LinkedIn and a lot of other things that I’m not familiar with and really haven’t been trained on how to do it.”

Some participants expressed discouragement at the difficulty of finding a stable and sustainable job despite a tight labor market. In their experience, competition for certain jobs was leading to less viable job opportunities and lower wages.

“I’ve seen much more competition when finding jobs like the ones I used to have…The positions are filling up quickly and I see there are a lot of people willing to work for less than we used to make, because you can tell they need it. I see there are more opportunities, but the pay is not attractive enough.”

Worker attributes and personal histories

Everybody was affected by COVID in different ways. So it could vary between age or race…it’s a lot that comes into it.

-Worker Voices participant

Many workers across the focus groups shared that being part of a particular demographic group, whether as a person of color, an undocumented worker, an older or justice-impacted worker, or having a disability, negatively impacted their experience in the pandemic labor market. Participants described these attributes as barriers to employment in the ways noted below.

Workers of color

During the pandemic, workers of color often faced worse health and financial outcomes compared to white workers. Mortality rates were higher among most groups of color compared to white Americans during the pandemic after adjusting for age (Hill, Artiga, and Ndugga 2023). People of color were overrepresented in front-line jobs, were less likely to work remotely, and were more likely to be exposed to COVID at work (Tomer and Kane 2020; Gould and Kandra 2021; Dubay et al. 2020). Additionally, people of color in general were more likely to be laid off and those without a bachelor’s degree experienced higher rates of unemployment (Boesch, Nunn, and Tchourumoff 2022; Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce n.d.). Some participants also described being treated differently or paid less because of their race and ethnicity.

“They have not been able to treat me nicely, because of my race and color….”

“It’s still hard for Latinos… We are working more and earning less. Latinos contribute with high-quality workmanship in this country, and they don’t appreciate it, because we are Latinos, because we are migrants.”

Justice involvement

Research has shown that a criminal record, no matter how long in the past, can limit employment opportunities, wealth building, and upward economic mobility (Agan and Starr 2017; Maroto 2015; Western and Pettit 2010). Justice-impacted workers in our focus groups shared their challenges navigating the labor market, employer bias, and a lack of opportunities. One participant described the social stigma and employer bias associated with having a criminal background. In addition to their record narrowing the range of jobs available to them, they felt trapped in low-wage work:

“[I]t is very hard to get away from your background…. A lot of people don’t have that forgiveness. They don’t have the understanding to understand it. That’s not who you are…So it’s hard for people to get jobs right now. And that’s why we have a lot of people working minimum wage.”

Individuals who have recently interacted with the justice system must also shoulder financial burdens associated with reentry (Beckett and Harris 2011). These burdens include court fees and fines, adhering to parole requirements, drug testing, and other challenges following their release (Beckett and Harris 2011; Peterson 2012). The same participant also shared the difficulty of finding a stable job with an employer that was willing to give them the flexibility to meet those requirements while on the job.

“[My employer was] willing to work with the days that I needed to be at our program and then to do—there is random days that I have to do drug testing…at any given moment I have to leave.”

Disability

Historically, the labor force participation rate of individuals with disabilities has been significantly lower than those without disabilities (Paul M. A. Baker et al. 2018). Several participants in our focus groups reported that having a disability created a unique set of circumstances and obstacles in their personal lives and in navigating the labor market. Among participants who indicated disability as a barrier to employment, one-quarter were working full time. One participant had been out of the workforce for years due to a disability:

“I’ve been out of work for the last three years due to a disability. So I’m just trying to get back out in the workforce because it’s more of a career change for me.”

In addition to the difficult task of reentering the job market, a few focus group participants noted that their disability made it harder to balance career advancement goals with the potential of losing their disability benefits. While this is not generally true, and there are government programs in place (to help mitigate these situations, similar scenarios can occur for some workers with disabilities in specific circumstances. (The Social Security Administration’s “Ticket to Work” is an example of a program created to help mitigate these situations.) For some individuals, a modest increase in income could lead their families’ income to exceed eligibility thresholds for public benefits, making them financially worse off than before the wage increase (Despard, n.d.). Even in circumstances in which this is not the case, the complexity of assistance programs may contribute to misunderstandings and apprehension among recipients about the prospect of engaging in paid work.

“Being on disability, I have to watch what I’m, the money I make every month so they would not turn off benefits because I take treatments every four months.”

“If I try to get a job, I’ll get penalized for it. So it’s basically like enforced poverty…basically, I can’t get a job right now, even though I actually want to.”

Citizenship status and language barriers

Three of the 19 Worker Voices focus groups were held in Spanish. Doing so provided insights from workers facing a distinct set of challenges in the labor market an opportunity to share their insights. Focus group participants were not asked directly about their legal status, but immigration, citizenship status, and language barriers were themes and challenges discussed by several participants in the Spanish language focus groups. Statistically, hispanic workers are over-represented in low-wage occupations relative to their share of the workforce (Ross and Bateman 2019). In addition, data show immigrant workers were disproportionately vulnerable to the negative economic impacts of the pandemic (Gelatt 2020).

In some instances, language barriers themselves were an impediment to employment. Nearly half of the workers in our sample who reported citizenship status as a barrier to employment also reported experiencing language barriers. Without a strong command of the English language, participants felt that they had limited bargaining power and job opportunities.

During the COVID crisis we, the migrants in New York, and all over the US, we had to go through difficult situations because we don’t have the right papers to work in the country.

– Worker Voices participant

Many undocumented workers in our sample reported finding themselves relegated to low-wage positions with little potential for advancement.

“Latinos, just because we don’t have the documents, our pay is very low.”

“Regarding the salary, they could tell you, for example, look, I can pay $15 an hour, do you take it or leave it? But a coworker is getting paid $20 an hour, but just because you’re an immigrant, you don’t have the documents in order, they pay you whatever they want.”

Participants in the Spanish language focus groups expressed feeling part of a community of individuals and workers that faced obstacles directly tied to their legal status and their identity as members of a racial and ethnic group. For many, these were discouraging factors in obtaining economic and social stability. Others felt that achieving economic mobility was a matter of perseverance and believed that overcoming barriers was a part of their journey to stability and economic mobility.

“I know that we have to keep fighting, I know that I will be a legal resident, and I will be able to do everything I want, and…achieve my goals. I really hope that our legal situation gets better, because that would allow us to have better job opportunities, to give a better life to our family.”

Older workers

Several of the older individuals in our focus groups reported experiencing a unique set of obstacles in finding and sustaining employment. These challenges included learning new skills, competing with younger workers, and accepting positions that did not make use of their skillset or experience.

“I was fired almost with insults, also because of my age. They just said, we don’t need you anymore, go away, there’s nothing more, we have nothing for you.”

“I’m an older adult now going back into the workforce… I’m competing with young people on these applications that I’m not comfortable with.”

Work-family conflicts

It’s kind of hard to dedicate yourself to an employer when you have children and you have to you know, be more cautious of their needs and your family needs first.

-Worker Voices participant

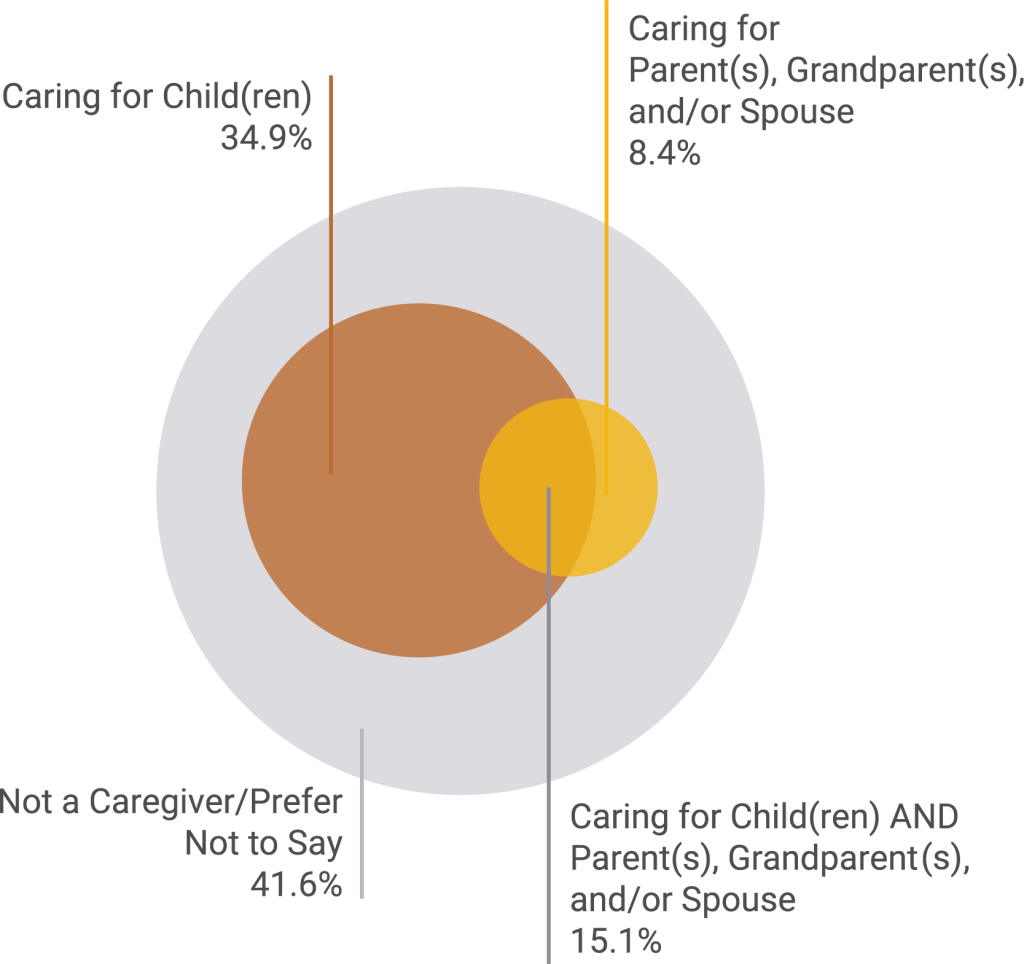

Many participants reported that balancing family caregiving responsibilities with work obligations became an especially acute challenge during the pandemic. More than half of project participants reported they were caregivers. Employment barriers associated with caregiving were discussed in nearly every focus group.

‘We can’t go out and get a stable job because we take care of grandchildren or children.”

Figure 2. Worker Voices Participants by Caregiving Role

Finding affordable and available childcare has long been a significant obstacle for caregivers, especially for low-income households (Koltai et al. 2021). The limited availability of childcare continued to make handling childcare responsibilities difficult in 2020 when most states mandated school closures (Igielnik 2021; Zviedrite et al. 2021).

“Once they decided to shut the school down due to COVID, the kids were doing virtual learning… I had to be home with them to do online, you know, learning… It was a little rough, because we didn’t know, you know, when the kids were going to return back to school.”

While 35 percent of our sample cared for children, caregiving concerns were not restricted to parents or caregivers of children. Nearly a quarter of participants reported being caregivers to their spouses, parents, or grandparents. Nearly one in six workers reported caring for both children and a parent, grandparent, or spouse. For some, the pandemic made existing time-based caregiving conflicts more difficult. Participants also stressed that the pandemic contributed to health-based family conflicts that were far less common prior to the pandemic. For example, given the fact that many participants were responsible for individuals considered high-risk for COVID, going into a physical work environment came with serious health risks.

“My mom actually forced me to stop working because she didn’t want the people in my household to be affected [sick]. I had to, like, quit that job because I didn’t want to endanger the people who I was living with. It was difficult to find another job.”

The conflict between caregiving responsibilities and work during the pandemic proved unsustainable for many. In some cases, participants lost jobs or quit altogether.

“Childcare wasn’t available… so I ended up losing my job because of that.”

The pandemic also forced some workers in our sample to become intermittent caregivers as family members became sick with COVID making consistent employment even more difficult.

“I couldn’t [keep my job] because my siblings got COVID… I had to help and take care of them.”

Several participants indicated that the response of their employer was the deciding factor in their ability to maintain employment through childcare disruptions. While some participants described empathetic and flexible supervisors, others spoke of employers unwilling to accommodate new caregiving responsibilities created by the pandemic.

“My youngest son’s childcare still closes for two weeks at a time…[My previous supervisor] would let me work from home …[but my new supervisor] basically fired me, because I wasn’t able to come to the office… I have been jumping ever since from job to job …I need that flexibility in order to keep my family afloat.”

Balancing individual well-being with employment

People lying or people that threaten to cough on me because I ask you to go outside if you’re not going to wear a mask, because that’s supposed to be our, the ropes that were put in place.

-Worker Voices participant

In addition to the potential health risks to family members, participants also reported health and safety concerns to themselves. Workers in personal care and service, healthcare, and retail jobs were at greater risk for COVID exposure (Baker, Peckham, and Seixas 2020). In addition, incidents of violent crime in many of these same workers’ places of employment also rose substantially during the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2021, incidents of violent crime at gas stations and grocery stores rose 58.6 percent and 42.2 percent respectively (Author’s Calculations, Federal Bureau of Investigation n.d.). Several focus group participants recounted feeling physically unsafe in the workplace. Concerns included those directly associated with exposure to COVID, as well as instances of poor treatment by customers.

“In times of desperation, human beings become much worse, just across the board. The tips and treatment were atrocious.”

In addition to the physical and health risks of COVID, the emotional toll of the pandemic became increasingly burdensome over time. Nearly one in five participants specifically cited mental health as an obstacle to finding or maintaining employment, and the issue was raised by participants in every focus group (Figure 3). These challenges were commonly characterized by participants as the result of burnout (which were often the result of labor shortages), unsupportive managers, and/or financial instability.

Figure 3. Percentage of Workers Citing Mental Health Challenges as Barrier to Work

| Age | |

|---|---|

| Ages 20-24 | 23.7% |

| Ages 25-34 | 17.9% |

| Ages 35-44 | 19.5% |

| Ages 45-55 | 15.8% |

| Gender | |

| Female | 21.1% |

| Male | 16.2% |

| Race & Ethnicity | |

| American Indian | 30.8% |

| Black or African American | 12.7% |

| White | 23.5% |

| Hispanic/Latin X | 16.7% |

| Not Hispanic/Latin X | 21.0% |

| Education | |

| Some College | 22.7% |

| High School Degree or Equivalent (HES, GED) | 21.3% |

| Associate’s Degree | 27.8% |

| Caregiver | |

| Caregiver | 18.8% |

| Not Caregiver | 17.2% |

| Employment Status | |

| Currently Working | 18.2% |

| Not Currently Working | 21.2% |

| Marital Status | |

| Single, Never Married | 23.6% |

| Married or Domestic Partnership | 8.9% |

| Divorced | 36.4% |

| Average Among All Participants | 19.4% |

During the pandemic, the rise in Americans quitting their jobs became a self-reinforcing dynamic due to a phenomenon known as turnover contagion (Porter and Rigby 2020). As workers in occupations such as retail, hospitality, and healthcare quit their jobs at elevated levels in 2021, many workers that remained on the job found themselves stretched thin and often took on additional responsibilities without a commensurate increase in pay (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “JOLTS – July 2021”).

“They don’t have enough people to work. And then, like, they leave us to do, like, our job and other people’s job, which [causes] a lot of stress. …It makes you not even want to work.”

Several workers in our focus groups struggled to deal with abusive customers or unsupportive managers. Some felt that employers treated them like they were disposable.

“You work 100 hours a week, and you don’t get offered time for if you get sick with COVID… You don’t get any type of compensation. You very much realize how little you matter.”

Based on these threats to their well-being, several participants reported quitting their jobs after reaching a breaking point.

“I had worked in the [COVID-19] unit for an entire year and a half, but from the stress and from everything that came with that experience, I decided to quit.”

“A lot of people started quitting. And as I proceeded to make management, it got to the point where I’m running around doing too many things and not equaling out the pay for all this work that I was doing… Eventually, it got stressful to the point where I had to leave.”

Participants without jobs also faced their own mental health challenges. At times, these mental health struggles were triggered by a sudden job loss. In other instances, participants cited extended periods of unemployment as the primary threat to their mental well-being.

“I get a call, come pick up a severance check, like an indefinite layoff…I was used to working, you know, five to six days a week…It got depressing.”

“During that period of time that we did receive unemployment, my mental health suffered tremendously…[I] couldn’t seem to grasp the seriousness of what was going on. And I think in some ways being kind of stifled with the depression and the fear.”

Regardless of their employment status, participants felt the stress of the pandemic. Several emphasized that the pandemic was among the most mentally taxing experience of their lives.

“It was scary. I was afraid. I’ve never experienced anything like that before in my life.”

Compounding effects of multiple barriers

Currently, I live in a family shelter…I’m trying to work on my credit while trying to find housing while trying to find a car while trying to find a job while trying to find childcare. Like it just, it just doesn’t stop.

-Worker Voices participant

The compounding effects of multiple barriers and economic challenges perpetuated and sometimes exacerbated the financial insecurity of many workers in our sample. Most focus group participants reported experiencing more than one barrier to employment during pre-session surveys and focus group discussions (Figure 1). Additionally, some barriers present more challenging obstacles to employment than others. Research has found that individuals facing barriers like homelessness, criminal convictions, mental health issues, or disabilities face greater difficulty securing and maintaining employment than those without such barriers (USC Price Center for Social Innovation – Homeless Policy Institute 2020; Solomon 2012; Cook 2006; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2022). Participants described experiencing multiple, sometimes intersecting barriers that had compounding negative effects on their ability to find and maintain a job.

Figure 4. Number of Additional Barriers to Employment Cited by Participants

In particular, seven barriers to employment seem to exacerbate workers’ difficulty finding and maintaining a job. As shown in Figure 4, participants who self-reported substance abuse, criminal convictions, homelessness, language barriers, mental health, citizenship status, or disability as a barrier to their employment typically identified a greater number of additional barriers than their peers who did not self-identify as experiencing one of these barriers. When describing their peers who did not self-identify as experiencing one of these barriers. When describing their challenges, participants noted that facing multiple barriers impacted their ability to obtain work.

“I became homeless…I had other jobs, but they didn’t pay [enough], so I couldn’t afford a motel…I have felonies…It’s kind of hard that when you have the experience and when you have the skills [for] these jobs, they will still look down on you.”

Additionally, during the pandemic, housing insecurity increased, public transportation availability decreased, and gasoline prices rose to a 25-year high (Grinstein-Weiss et al. 2020; Kar et al. 2022; U.S. Energy Information Administration 2023). Participants relayed that housing and transportation challenges and the tradeoffs associated with these increased costs impacted the jobs they were willing to take, their ability to sustain employment, or both.

“The cost of living is so high, inflation is so high…you can’t even afford your rent. Sacrifice of food, compared to lodging in today’s economic world. And those decisions come into play when it comes to choosing a job.”

“The major issue I had [was] with transportation…I didn’t have money to waste whether for buses that would take me to work and bring me back…I have children. So, I had problems with accessing childcare.”

Conclusion

The employment barriers reported by participants are striking given the strong macroeconomic environment during which the Fed conducted these Worker Voices Project focus groups. Despite labor statistics that largely suggested a favorable labor climate, workers and job seekers without a 4-year degree in our focus groups repeatedly emphasized the difficulty of identifying, securing, and maintaining a quality job. Given that most participants described experiencing multiple barriers to employment, effectively mitigating such obstacles may require a more holistic understanding of the compounding effects of multiple barriers facing non-degreed workers and workers in low-wage roles.

The seeming disconnect between quantitative labor market data and the experiences of participants underscores the value of gathering the views of workers and job seekers. Between July 2022 and July 2023, for example, the number of job openings declined by more than 20 percent (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “JOLTS – July 2023”). Given that many of the difficulties participants described in navigating the labor market may become even more acute with lower numbers of job openings and rising unemployment, policymakers, employers, and workforce intermediaries should consider incorporating worker insights into efforts to mitigate these challenges and ultimately facilitate sustained labor market attachment for this group of workers.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the Federal Reserve System or Fed Communities.

Please cite this work as: Galeano, Sergio, John Rees, and Elizabeth Bogue Simpson. 2023. Worker Voices Special Brief: Barriers to Employment. Fed Communities. https://doi.org/10.59695/20231115.

Media inquiries: Contact Monique Broughton Knight, Atlanta Fed.

Research: Please direct inquiries about the research, data, and methodology in this report to Sergio Galeano, John Rees, and Elizabeth Bogue Simpson.

Appendix: Methodology

For this special brief, we analyzed data from the pre-session demographic questionnaire and transcripts from 19, 90-minute focus groups conducted virtually between May 2022 and September 2022 as part of the Federal Reserve System’s Worker Voices project. We used a convenience sampling method, and participants were primarily recruited through workforce development and other worker-serving organizations. As such, this sample is biased toward participants who were engaging with such organizations. The pre-session screener questionnaire and focus group sessions covered a variety of work-related topics, several of which focus on barriers to obtaining and sustaining quality employment which are examined in this brief (Miller et al. 2023).

We used thematic, inductive qualitative analysis to identify commonly discussed subjects related to barriers to obtaining or maintaining employments as described by project participants (Proudfoot 2023; Dunne and Wardrip 2023). We analyzed 370 references to barriers to employment, which were found in each focus group and were identified in the initial inductive coding phase. We also identified sub-themes within barriers to employment, including benefits cliffs, changes in hiring, childcare and other caregiving responsibilities, disability or illness, justice involvement, lack of specific skills or credentials, transportation, and vaccine or other COVID-19 related requirements.

In addition to analyzing focus group transcripts, we analyzed participants’ responses from the pre-session screening questionnaire that was used to determine participant eligibility. The two inclusion criteria for this project were that the individual: 1) had not completed a bachelor’s degree and 2) were aged 20-55. In regards to the section on older workers, the authors used a broader definition of ageism that includes bias against workers of any age.

The screening questionnaire requested demographic information and asked participants to self-report if they had experienced any of the following barriers to employment: disability, mental health challenges, criminal convictions, substance abuse, homelessness, citizenship status, language barriers, COVID-19, lacking skills, transportation, available childcare, affordable childcare, and other. Our analysis may not include individuals who faced a barrier or barriers but chose not to disclose them. Responses to this question, along with participants’ mentions of barriers that were coded from focus group transcripts, were used to analyze the prevalence of these barriers in our sample.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the focus group participants whose experiences and contributions formed the foundation for the Worker Voices Project, both generally and for this brief specifically. We would also like to thank the following people for their feedback and contributions to this brief.

Ann Carpenter, f. Atlanta Fed

Merissa Piazza, Cleveland Fed

Keith Wardrip, f. Philadelphia Fed

Sarah Miller, Atlanta Fed

Carl Van Horn, John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development

Tiffani Williams, Atlanta Fed

References

Abel, Jaison R., Richard Florida, and Todd M. Gabe. “Can Low-Wage Workers Find Better Jobs?” Staff Report No. 846. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2018. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3164963.

Agan, Amanda, and Sonja Starr. “The Effect of Criminal Records on Access to Employment.” American Economic Review 107, no. 5 (May 2017): 560–64. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.p20171003

Baker, Marissa G., Trevor K. Peckham, and Noah S. Seixas. “Estimating the Burden of United States Workers Exposed to Infection or Disease: A Key Factor in Containing Risk of COVID-19 Infection.” PLOS ONE 15, no. 4 (April 28, 2020): e0232452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232452.

Baker, Paul M.A, Maureen A. Linden, Salimah S. LaForce, Jennifer Rutledge, and Kenneth P. Goughnour. “Barriers to Employment Participation of Individuals With Disabilities: Addressing the Impact of Employer (Mis)Perception and Policy – Paul M. A. Baker, Maureen A. Linden, Salimah S. LaForce, Jennifer Rutledge, Kenneth P. Goughnour, 2018.” American Behavioral Scientist 62, no. 5 (May 1, 2018): 657–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218768868.

Bateman, and Martha Ross. “The Pandemic Hurt Low-Wage Workers the Most—and so Far, the Recovery Has Helped Them the Least.” Brookings Institute, July 28, 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-pandemic-hurt-low-wage-workers-the-most-and-so-far-the-recovery-has-helped-them-the-least/.

Beckett, Katherine, and Alexes Harris. “On Cash and Conviction.” Criminology & Public Policy 10, no. 3 (August 2011): 505–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00727.x.

Bergman, Nittai, David A. Matsa, and Michael Weber. “Inclusive Monetary Policy: How Tight Labor Markets Facilitate Broad-Based Employment Growth.” Working Paper. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2022. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29651.

Bergson-Shilcock, Amanda, Roderick Taylor, and Nye Hodge. “Closing the Digital Skill Divide.” National Skills Coalition, February 6, 2023. https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/closing-the-digital-skill-divide/.

Boesch, Tyler, Ryan Nunn, and Altene Tchourumoff. “Occupational Segregation Left Workers of Color Especially Vulnerable to COVID-19 Job Losses.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, February 7, 2022. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/occupational-segregation-left-workers-of-color-especially-vulnerable-to-covid-19-job-losses.

Carnevale, Anthony P., Ban Cheah, and Emma Wenzinger. “The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings.” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2021. https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/cew-college_payoff_2021-fr.pdf.

Cook, Judith A. “Employment Barriers for Persons With Psychiatric Disabilities: Update of a Report for the President’s Commission.” Psychiatric Services 57, no. 10 (October 2006): 1391–1405. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1391.

Daly, Mary C, Shelby R. Buckman, and Lily M. Seitelman. “The Unequal Impact of COVID-19: Why Education Matters.” FRBSF Economic Letter 2020–17 (June 29, 2020). https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2020/june/unequal-impact-covid-19-why-education-matters/.

Despard, Mathieu. 2023. “Benefits Cliffs: Effects on Workers and the Role of Employers.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, n.d. https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/USCCF_BenefitsCliffsBrochure_Digital.pdf

Dubay, Lisa, Joshua Aarons, Steven Brown, and Genevieve M. Kenney. “How Risk of Exposure to the Coronavirus at Work Varies by Race and Ethnicity and How to Protect the Health and Well-Being of Workers and Their Families – Digital Collections – National Library of Medicine.” The Urban Institute Health Policy Center, December 2, 2020. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-9918266201306676-pdf.

Dunne, Theresa, and Keith Wardrip. “Worker Voices Special Brief: Perspectives on Job Quality.” Fed Communities, September 25, 2023. /research/worker-voices/2023-job-quality-perspectives-special-brief/.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Crime Data Explorer.” Accessed October 17, 2023. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend.

Ferguson, Stephanie. “Understanding America’s Labor Shortage: The Most Impacted Industries.” U.S. Chamber of Commerce, March 23, 2023. https://www.uschamber.com/workforce/understanding-americas-labor-shortage-the-most-impacted-industries.

Gelatt, Julia. “Immigrant Workers: Vital to the U.S. COVID-19 Response, Disproportionately Vulnerable.” Migration Policy Institute, March 26, 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigrant-workers-us-covid-19-response.

Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce. “Tracking COVID-19 Unemployment and Job Losses.” Accessed March 30, 2023. https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/jobtracker/.

Gould, Elise, and Jori Kandra. 2021. “Only One in Five Workers Are Working from Home Due to COVID: Black and Hispanic Workers Are Less Likely to Be Able to Telework.” Economic Policy Institute, n.d. https://www.epi.org/blog/only-one-in-five-workers-are-working-from-home-due-to-covid-black-and-hispanic-workers-are-less-likely-to-be-able-to-telework/.

Grinstein-Weiss, Michal, Brinda Gupta, Young Chun, Hedwig Lee, and Mathieu Despard. “Housing Hardships Reach Unprecedented Heights during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Brookings Institute, June 1, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/housing-hardships-reach-unprecedented-heights-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Hill, Latoya, Samantha Artiga, and Nambi Ndugga. “COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity as of Winter 2022.” KFF, March 7, 2023. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-deaths-and-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-winter-2022/.

Igielnik, Ruth. “A Rising Share of Working Parents in the U.S. Say It’s Been Difficult to Handle Child Care during the Pandemic,” January 26, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/26/a-rising-share-of-working-parents-in-the-u-s-say-its-been-difficult-to-handle-child-care-during-the-pandemic/.

Jayashankar, Aparna, and Anthony Murphy. “High Inflation Disproportionately Hurts Low-Income Households.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, January 10, 2023. https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2023/0110.

Kar, Armita, Andre L. Carrel, Harvey J. Miller, and Huyen T.K. Le. “Public Transit Cuts during COVID-19 Compound Social Vulnerability in 22 US Cities.” Transportation Research. Part D, Transport and Environment 110 (September 2022): 103435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103435.

Kinder, Molly, and Martha Ross. “Reopening America: Low-Wage Workers Have Suffered Badly from COVID-19 so Policymakers Should Focus on Equity,” June 23, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/reopening-america-low-wage-workers-have-suffered-badly-from-covid-19-so-policymakers-should-focus-on-equity/.

Koltai, Jonathan, Jess Carson, Tyrus Parker, and Rebecca Glauber. “Childcare Remains Out of Reach for Millions in 2021, Leading to Disproportionate Job Losses for Black, Hispanic, and Low-Income Families.” University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy, December 2021. https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/childcare-remains-out-of-reach-for-millions-in-2021.

Konkel, AnnElizabeth. “Job Ads Noting Fair Chance Hiring Rise in Tight Labor Market.” Hiring Lab: Economic Research by Indeed, June 9, 2022. https://www.hiringlab.org/2022/06/09/fair-chance-hiring-job-ads-rise/.

LaBerge, Laura, Clayton O’Toole, Jeremy Schneider, and Kate Smaje. “How COVID-19 Has Pushed Companies over the Technology Tipping Point—and Transformed Business Forever.” McKinsey & Company, October 5, 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/how-covid-19-has-pushed-companies-over-the-technology-tipping-point-and-transformed-business-forever.

Maroto, Michelle Lee. 2015. “The Absorbing Status of Incarceration and Its Relationship with Wealth Accumulation.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 31 (August 22, 2014): 207–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9231-8.

Miller, Sarah, Merissa Piazza, Ashley Putnam, and Kristen Broady. “Worker Voices: Shifting Perspectives and Expectations on Employment.” Fed Communities, May 24, 2023. /research/worker-voices/2023-shifting-perspectives-expectations-employment/.

Peterson, Paul. “Supervision Fees: State Policies and Practice.” Federal Probation 76, no. 1 (2012): 40–45.

Porter, Caitlin M., and James R. Rigby. 2021. “The Turnover Contagion Process: An Integrative Review of Theoretical and Empirical Research.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 42, no. 2 (September 17, 2020): 212–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2483.

Proudfoot, Kevin. 2023. “Inductive/Deductive Hybrid Thematic Analysis in Mixed Methods Research.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 17, no. 3 (September 20, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898221126816.

Ross, Martha, and Nicole Bateman. “Meet the Low-Wage Workforce.” Brookings Institute, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/201911_Brookings-Metro_low-wage-workforce_Ross-Bateman.pdf.

Solomon, Amy L. 2012. “In Search of a Job: Criminal Records as Barriers to Employment.” National Institute of Justice Journal, no. 270 (June). https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/search-job-criminal-records-barriers-employment.

The Burning Glass Institute. “The Emerging Degree Reset,” 2022. https://www.burningglassinstitute.org/research/the-emerging-degree-reset.

Tomer, Adie, and Joseph W. Kane. “To Protect Frontline Workers during and after COVID-19, We Must Define Who They Are.” Brookings Institute, June 10, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/to-protect-frontline-workers-during-and-after-covid-19-we-must-define-who-they-are/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “12-Month Percentage Change, Consumer Price Index, Selected Categories.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. n.d.a. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/charts/consumer-price-index/consumer-price-index-by-category.htm.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Civilian Unemployment Rate.” n.d.b. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/civilian-unemployment-rate.htm#b.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover – July 2021.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_09082021.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover – July 2023.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_08292023.pdf.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover – May 2020.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_07072020.pdf.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “JOLTS Home.” n.d.c. Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/jlt/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Persons With A Disability: Barriers to Employment, Types of Assistance, and Other Labor-Related Issues Summary,” March 30, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/dissup.nr0.htm?msclkid=dcef0bb2b9bb11ecb57867bd5bca51a5.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Unemployment Rate Rises to Record High 14.7 Percent in April 2020,” May 13, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-rises-to-record-high-14-point-7-percent-in-april-2020.htm.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Unemployment Rates for Persons 25 Years and Older by Educational Attainment.” n.d.d. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/charts/employment-situation/unemployment-rates-for-persons-25-years-and-older-by-educational-attainment.htm.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Educational Attainment in the United States: 2022,” February 16, 2023. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/demo/educational-attainment/cps-detailed-tables.html.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “U.S. All Grades All Formulations Retail Gasoline Prices (Dollars per Gallon).” Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=emm_epm0_pte_nus_dpg&f=m.

USC Price Center for Social Innovation – Homeless Policy Research Institute. “Homelessness and Employment,” August 24, 2020. https://socialinnovation.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Homelessness-and-Employment.pdf.

Western, Bruce, and Becky Pettit. “COLLATERAL COSTS: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility.” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2010. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/3975EB366428437FADA60843AA02C2FC.ashx.