Worker Voices Special Brief: Perspectives on Job Quality

By Theresa Dunne, Keith Wardrip

September 25, 2023

In this brief, we present the results of our analysis of focus groups conducted with noncollege workers (i.e., workers without a four-year college degree) during the economic recovery from the COVID-19 recession to understand the critical elements of job quality as described by the research participants. The 18 focus groups that inform this analysis were conducted between May 2022 and September 2022 as part of the Federal Reserve System’s Worker Voices Project, which sought to learn about workers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery. This brief is one of several deep dives into important topics raised during these focus groups but too rich to cover thoroughly in the full Worker Voices report (“full report”). In this brief, we enrich the discussion of job quality begun in the full report by answering the question: How did noncollege workers participating in nationwide focus groups describe a quality job?

For these workers, at that moment in time, adequate compensation was described as a necessary, but not sufficient, component of a quality job. First and foremost, a quality job pays well enough to cover the bills without concern and allows a little cushion for discretionary expenses and savings. Further, compensation reflects a worker’s level of responsibilities and sense of self-worth, is predictable, and includes benefits. In a quality job, workers are treated well, as valued and respected team members. A quality job is safe and secure, not subject to an unexpected layoff, and permanent, not temporary. Family and personal needs are not sacrificed if one has a quality job because its hours and location are flexible, and it allows for a work-life balance. Finally, a quality job is enjoyable, manageable, and fulfilling.

This conceptualization of job quality was influenced by, and stands in stark contrast to, participants’ work experiences in the months and years preceding these conversations—experiences characterized by a fear of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to their families, a feeling of being unprotected or unsupported at work, and the generally difficult working conditions during the economic recovery.

Background

Job quality can be defined in a variety of ways. For the purposes of this brief, we gravitate toward this straightforward option: “the characteristics of work and employment that affect the well-being of the worker” (Muñoz de Bustillo et al. 2011, p. 460)—or even more to the point, “well-being from work” (Clark 2015, p. 2). In spite of—or perhaps because of—the simplicity of these definitions, there is no universally agreed-upon way to measure or operationalize job quality. Our scan of the literature found proposals that ranged from superficial definitions with easy-to-measure inputs such as weekly wages (Alpert et al. 2019) to “menus” with more than 30 often amorphous and unquantifiable elements such as “mattering” (Dawson 2018).

While far from comprehensive, Figure 1 shows the elements of job quality we found to be most commonly cited in our review of recent definitions. We include Figure 1 only to make the discussion of job quality more concrete, not as an endorsement of the particular elements listed.

Figure 1. Sample of Job Quality Elements from the Literature

| Career advancement opportunities | Power to change things about the job |

| Control over hours, location, or schedule | Sense of purpose or dignity in the work |

| Employee benefits | Stable and predictable hours |

| Job security | Stable and predictable pay |

| Level of pay | Working conditions |

Note: This list was compiled beginning with the job quality characteristics included in Rothwell and Crabtree (2019) and modified based on our review of the literature.

While there may be no agreed-upon definition of job quality, interest in measuring trends, levels, and disparities in job quality has generated a substantial amount of research on the topic. Objective assessments of job quality generally rely on surveys that gather information about the characteristics of the jobs held by respondents. In the US, some long-running and wide-ranging data collection efforts, such as the Current Population Survey, capture relatively thin information about the quality of work (for example, wages or access to benefits). These more general surveys have been complemented by others focused specifically on job quality, such as the RAND Corporation’s American Working Conditions Survey and Gallup’s Great Jobs Survey. Although surveys and the research predicated on them offer different data and different definitions of job quality, respectively, the findings most germane to this brief suggest that workers with less education and non-White workers are less likely than others to hold jobs with better wages, full-time hours, access to benefits, and other markers of job quality (Kalleberg 2011; Fee 2022; Rothwell and Crabtree 2019; Schudde and Bernell 2019; Shakesprere et al. 2021). Noncollege workers do not have the same schedule flexibility that college-educated workers have, are more frequently subject to unpredictable changes to their work schedules, and face more difficulty when trying to take time off for personal or family needs (Maestas et al. 2017). Relative to those with higher incomes, lower-income workers are far less likely to hold a “good job” and have access to benefits, and they are more likely to spend their days doing repetitive or physical tasks rather than being creative or innovative (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019; Gallup, Inc. 2020).

Objective measures of job quality can tell us only so much, however. There is general agreement that perceptions of job quality vary among workers depending on their life circumstances and priorities (Clark 2015; Congdon et al. 2020; Brett and Woelfel 2016; Dawson 2018). For instance, a younger worker may value skill-building and career advancement more than an older worker, who may place a higher priority on a reasonable schedule and working conditions that are less physically taxing (Belardi et al. 2023). Further, depending on their preferences, a worker may view a job as good even if it has objectively bad characteristics (Knox et al. 2015), and this determination can be influenced not only by their personal preferences but also by their broader community context and their assessment of available alternatives (Cooke et al. 2013).

The national surveys conducted by RAND and Gallup (mentioned previously) stand out because they also asked respondents about the importance of various job characteristics. According to the RAND survey, workers frequently rate job attributes such as being able to financially provide for oneself and one’s family, having job security, and having health insurance and paid time off (PTO) as essential or very important (Maestas et al. 2017). Research using Gallup survey data suggests low-income workers place high importance on their enjoyment of day-to-day work, stable and predictable pay, a sense of purpose, job security, and level of pay, in that order. Lower on the list are items such as career advancement opportunities and control over hours or location (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019). Additional analysis of Gallup survey data suggests that relative to those with a four-year college degree, a greater share of noncollege workers consider level of pay and stable and predictable hours extremely important (Scott and Katz 2021).

Surveys generate invaluable insights into job quality, but they are not without their drawbacks. One is that, given a menu of options, respondents may suggest that everything is a priority. For example, at least 64 percent of respondents at all levels of income rated each of 10 job quality elements as important (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019). Further, surveys are limited in what they can reveal about job quality because they offer a predetermined set of questions and answers. In other words, surveys cannot discover things they are not designed to measure and offer little in the way of nuance. Qualitative research is uniquely suited to fill these gaps.

A substantial amount of qualitative research has investigated the topic of job quality. Given the time-intensive nature of data collection, often through in-depth interviews and case studies, much of this work has pursued an understanding of job quality from the perspectives of workers in specific occupations, industries, or workplace settings (e.g., Knox et al. 2015; Osterman 2017; Leidner 1993). By contrast, the Worker Voices Project gives us a rare opportunity to analyze nuanced, open-ended conversations exploring job quality with scores of noncollege workers and job seekers from a variety of professional backgrounds across the country. We take a ground-up approach to our analysis, listening to these workers and identifying the most prominent themes discussed through these focus groups. If considered and adopted by employers, a greater understanding of what constitutes a quality job could not only improve worker well-being but also lead to a stronger bottom line by reducing the costs associated with job vacancies and high turnover rates (Boushey and Glynn 2012; Moon et al. 2022; Fuller and Raman 2022).

Data and methods

In this brief, we share the results of our analysis of transcripts from 18 focus groups conducted virtually between May 2022 and September 2022 as part of the Federal Reserve System’s Worker Voices Project. This national data collection effort and the subsequent full report covered the breadth and depth of pandemic-era labor market experiences of roughly 170 individuals between the ages of 20 and 55 who did not have a four-year college degree. Recruitment for this initiative was conducted through worker-serving organizations, job training providers, and workforce agencies.

While focus group questions covered a variety of work-related topics, participants were not explicitly asked to define job quality. However, several questions prompted participants to reflect on this topic and yielded rich information that we interpret through a job quality lens in our analysis of the transcripts. In Miller et al. (2023), see Appendix C for the focus group facilitation guide.

We used a combination of deductive and inductive techniques to identify, code, organize, and summarize participants’ statements about job quality. Please see the appendix for more on our qualitative research methods.

COVID as context

The Federal Reserve System conducted the focus groups informing this analysis in mid-2022, when both the public health and employment crises related to the COVID-19 pandemic were on the decline. The two years preceding the focus groups, however, were turbulent for many workers—noncollege workers in particular (Edwards et al. 2022)—and the facilitation guide was designed to learn more about participants’ experiences in the labor market leading up to these conversations. These experiences offer important context for how participants discussed job quality.

As it relates to the pandemic, the overriding sentiment expressed by focus group participants was fear: the fear of catching COVID-19 at work and the fear of putting family members at risk. Many participants worked in front-line roles—for example, as bartenders, cooks, delivery drivers, medical assistants, or waiters—that could not be done remotely, increasing their risk of exposure. In the words of one participant, “I don’t even know how to explain the fear that I had, just because everybody was dying. That was when I went back to work.”

Focus group participants often commented on the protocols their employers implemented to limit the spread of the virus. While some praised their employers for protecting their health, transitioning quickly to remote work, or enforcing social distancing in the workplace, others reflected on their employers’ efforts negatively, remarking on a lack of seriousness around implementation, a disregard for employee health and safety, and a lack of support from management. In light of their heightened vulnerability to exposure and the lax implementation of safety measures, participants said they were placing a high priority on their health as they searched for a new job. One remarked, “So, I think when I continued, you know, to look for new job or working with the same company, it’s just the seriousness of it all and making sure that we are following protocol.”

I don’t even know how to explain the fear that I had, just because everybody was dying. That was when I went back to work.

– Worker Voices participant

Finally, participants described the stress and strain of working during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to commenting on the anxiety surrounding the risk of contagion, many reported generally difficult working conditions and being overworked because of staffing shortages. As an example, one participant described their experience working at a hotel by saying, “If anything, we got overworked because people were quitting left and right, whether they were getting sick or scared to be getting sick. Which agitated the owners. And we caught the backlash of that.”

These experiences are intimately related to job quality, but they are also intimately linked to a moment in time. In the following section, we explore the constituent elements of a quality job, as expressed by focus group participants, that transcend pandemic-era labor market experiences. However, it is important to keep in mind the public health crisis and the ways it affected work and workers in the lead-up to these conversations. They are entangled in, and help illustrate, the broader themes that follow.

Participants’ perspectives on job quality

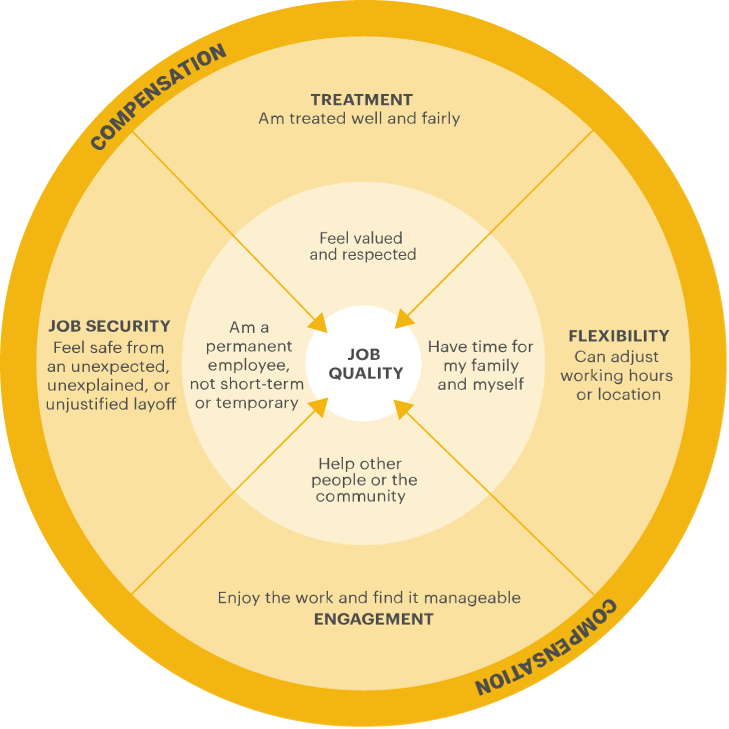

In this section, we discuss five primary themes that capture the sentiments related to job quality most strongly expressed by focus group participants. Figure 2 previews these themes. In the figure, compensation, as the most prominent theme and the foundation for a quality job, encircles the other critical components of treatment, job security, flexibility, and engagement. As the authors of the full report note and this figure suggests, participants discussed compensation as an “immediate qualifier or disqualifier” (Miller et al. 2023, p. 20) when considering a job, but one that is weighed alongside other job quality attributes. For each of the other four primary themes, subthemes that were more prominent in the focus group transcripts are provided in the middle ring of the figure, while less prominent subthemes are listed in the inner ring.

We phrase the subthemes in the figure and following sections to complete the statement, “A quality job is one in which I…” for the sake of presentation, but as we noted previously, focus group participants were not explicitly asked to define job quality; rather, these subthemes represent our interpretation of participants’ comments related to job quality that arose during these broader labor market conversations.

Figure 2. Elements of Job Quality Expressed by Focus Group Participants

The subthemes shown in the figure finish the statement, “A quality job is one in which I…”

compensation

Wages were front and center for focus group participants. General statements about being poorly paid and, conversely, the importance of being adequately compensated, were commonplace, as were statements explaining how wage levels affected decisions to leave or return to a job or to pursue a new opportunity. The high inflationary environment of 2022 was also on the minds of participants as real hourly and weekly wages (after adjusting for inflation) fell nationally (BLS 2023). Some participants discussed weighing the pay being offered against the value of their time or the cost of gasoline necessary to commute to distant jobs or to perform delivery-related gig or contract work.

In addition to these more general statements about the importance of pay, participants discussed compensation in ways that could be used to identify specific elements related to job quality. For focus group participants, a quality job is one that pays them enough to support themselves and their family. For some participants, such a job simply allows them to cover their bills without worry; for others, it also provides a cushion for discretionary expenses and savings. Pay is aligned with responsibilities and level of effort and matches workers’ sense of self-worth. Participants also suggested that the compensation package for a quality job includes benefits; given the public health context, it is not surprising that paid sick leave was most prominent among the specific benefits mentioned, which also included tuition reimbursement, PTO, health insurance, and 401(k) plans. Finally, a quality job delivers a reliable level of income, which runs counter to the experience of some participants who discussed reduced hours, lower-than-expected pay, and the instability of income from gig or contract work.

The theme of compensation intersects with two cross-cutting issues that emerged during these conversations: entrepreneurship and discrimination. Whether discussing their aspirations for owning their own business or their experiences in the gig economy, some participants reflected on entrepreneurship as a way to achieve “financial freedom” or “financial stability;” the ability to control their financial fate rather than depending on an employer for higher wages was articulated by a number of participants. Furthermore, some participants touched on the ways in which discrimination against immigrants and undocumented workers can lead to below-market wages and wage theft, highlighting an additional barrier to job quality for this group of workers.

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES RELATED TO COMPENSATION FROM WORKER VOICES PARTICIPANTS

A quality job is one in which my compensation…

Supports me and my family financially

“If it’s $15 an hour, I don’t mean to sound ungrateful—and that may work for some people—but I have four boys, not one, so that means I’ve got to work more jobs if I’m only making $15 an hour.”

“Getting out what you put in, and a livable wage where you can—you’re not just scraping by getting your bills paid, but you actually have a little bit to put away, do the things you need to do to raise your kids right, to make sure that they’re happy.”

Reflects my worth, effort, and level of responsibility

“We’re both now with companies that pay us what we’re worth, because it really opened my eyes while I was working at both locations during the pandemic that they didn’t care. Like, this is what you will do, and you are owned by us, and you’ll do it or whatever. You don’t have a job. That’s really how I felt.”

“I remember actually, we were trying to fight for more pay, because us as supervisors, we were getting $14. But then one of the crew members was getting $13.75. So, we were only getting a quarter more than a crew member. So, that definitely influenced me to kind of just not want to work there anymore.”

Includes benefits

“Unfortunately, a lot of people work for employers that didn’t even give them any pay if they were sick due to COVID. I was just blessed to have one that did.”

“Well, I thought I was going to get some benefits, maybe, you know, a little health insurance. Being just a variable-hour employee, you don’t get any of that stuff. You don’t get a 401(k). You don’t get no health benefits, none of that stuff that you look for from a quality employer.”

Is predictable

“I actually went to go through different jobs in the city, and I found a lot of issues where either the work environment was toxic or they would just cut your hours without even any explanation.”

“I did that for about six months, but the pay was really not worth my time. There was a lot of moments when I would sit in high, you know, busy areas for three hours and I would get one, maybe two deliveries.”

TREATMENT

In their comments related to job quality, focus group participants frequently described the importance of how they were treated by managers, customers, and other employees. Because of the timing of the interviews, these comments often pertained to the implementation of COVID safety protocols, but others transcended the public health crisis.

In a quality job, employers create a good work environment rather than a toxic one. They are understanding and take care of their employees. Apart from their day-to-day treatment in the workplace, participants also said that they want to be considered valuable team members capable of making important contributions and deserving of respect. In a quality job, employers listen to their employees’ opinions, show appreciation, and include them in the decision-making process.

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES RELATED TO TREATMENT FROM WORKER VOICES PARTICIPANTS

A quality job is one in which I…

Am treated well and fairly

“I’d been working there for about a month, and I actually had COVID, like, a couple weeks ago, but they were, like, way more understanding about it, and I had called out a few times for when I was sick, and I had doctors’ notes, but like they still are very accepting and helpful.”

“Like, yes, I am one of their workers, but I also am a person and, you know, my health comes first, and pay is nice to see. Like that they are paying you for what you are valued for, but also, just having a good work environment, and I think it’s just knowing that having a good work environment, like, can keep your employees around much longer than treating them not so good.”

“So, I also worked at a car wash. It was a bad experience because my boss was bad-tempered. He was angry. I’m 48 years old. At my age, you don’t want to tolerate that, so, I had to get out of there.”

Feel valued and respected

“I was looking for someone who would accept me as part of their team, accept me as someone who is working together with everyone to help this company strive. I didn’t want to be just another pair of hands doing something.”

“And then, the place I work for is pretty good about showing appreciation for their employees, whether it’s birthdays, gift cards, or just random drawings. I don’t know. They’re pretty—they show that we’re appreciated, which helps. So, I’m grateful for that.”

job security

Among focus group participants, job security stood out as another defining characteristic of a quality job. The sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic caused some participants to experience unanticipated furloughs or layoffs as businesses scaled back their operations or closed. In other instances, participants recounted being fired for needing extended sick time or for voicing COVID-related concerns. As such, participants described a quality job as one that allows employees to feel safe from unexpected, unexplained, or unjustified layoffs.

Participants also expressed the challenges of finding and maintaining permanent employment over the course of the pandemic, leading them to take on temporary or short-term work. Quality jobs are permanent jobs; they provide employees with stability and a guaranteed source of income. For participants with temporary work experience, permanent employment offered a reprieve from the stress of constantly searching for a new job once the temporary position ended.

Cross-cutting issues of entrepreneurship and discrimination also emerged amid discussions of job security. Some participants viewed entrepreneurship as a way they could achieve stability in an unpredictable job market, highlighting the importance of being able to depend on oneself, rather than on an employer, for a job. One participant explicitly connected discrimination to job security, saying: “…migrants are the first people they fire … I could be fired at any time.”

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES RELATED TO JOB SECURITY FROM WORKER VOICES PARTICIPANTS

A quality job is one in which I…

Feel safe from an unexpected, unexplained, or unjustified layoff

“I actually didn’t stop working. I got laid off, I guess because of COVID. I don’t know. They never gave me a reason anyways, but it was pretty much stressful because most of the places was closed down. So it was, like, impossible to even—to apply for another job or anything. I wasn’t able to get unemployment, they told me, because I got laid off. I’m not sure why, but so, it was, like, a big struggle for me.”

“However, because I was on oxygen 24/7, they were not allowing me to come back to work, and they were the ones who told me I could not come back to work because I was on oxygen, and then, one month after I got COVID, they fired me via certified mail saying I had three days of no call/no show, even though I had been out, at that point, for almost 30 days.”

“But I ended up looking for a new employer because of [layoffs], because I didn’t feel safe anymore, because I didn’t feel like someone would come and tell me, ‘Hey, look, times are tough, and if we get back on our feet, we’d love to have you back, but right now it looks like this is where we’re going to be.’ I think that would have went over a lot better for people than, ‘Hey, come in, we want to make sure your mouses and keyboards work, but you don’t have a job any more,’ so that side of it I think was horrible.”

Am a permanent employee, not short-term or temporary

“So, I found a work from home job, but it was temp to perm. So, it didn’t actually last as long as I wanted it to.”

“And also, [I’ve] been available for temporary work, but they’ll tell you that it’s a permanent job and then once your day is over with them, you become unemployed again. And then you don’t qualify for [state] unemployment or anything. So, then you’re hopping from job to job, and your resume sort of looks sloppy. And I’m just trying to figure out, you know, what ways we can learn how to stay employed through actual companies and not have to be temporary workers in the [local] area.”

flexibility

Focus group participants emphasized flexibility with hours and location as important facets of job quality, both in reference to the rise of remote work at the start of the pandemic and in more general terms. Some participants wanted the ability to adjust their hours or to work remotely to care for children or parents; others wanted to work remotely to reduce their risk of contracting COVID-19. Further, some wanted a remote work option because it made their working environment more manageable or comfortable. Having control over one’s time and schedule was raised by a number of participants as an attractive feature of entrepreneurship and gig work. Finally, participants underscored that a quality job allows them to achieve a healthy work-life balance, whether that means having time for themselves or spending time with family. Ultimately, a job’s flexibility was frequently mentioned as an indicator of a quality job and a characteristic that participants would seek in future employment opportunities.

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES RELATED TO FLEXIBILITY FROM WORKER VOICES PARTICIPANTS

A quality job is one in which I…

Can adjust working hours or location

“So I have to have a job that allows me enough time to get out of work and be at her school by 5:00 so I’m not charged extra money, or she’s not left there after school.”

“I just wanted to say that I agree with [another participant’s] statement, where I’m trying to look more for a job remotely for my health.”

Have time for my family and myself

“I can work from home most of the time and then go in the office if I want to, and it pays decently, and you know, I’m able to spend time with my family. So, this job is for, at the moment, good for me.”

“[Flexibility is] very important because, I mean, you don’t just want to work and then you don’t have any time to spend with your family. I mean, what is the essence of the work? I mean, why are you working? You are working so you could gain wages to give your family a good life, you know, and also have time to spend with your family.”

engagement

Focus group participants placed a high priority on doing work that they found enjoyable, stimulating, and impactful—sentiments that we group under the theme of engagement. As described previously, many participants discussed the staffing shortages and heavy workloads common during the pandemic, which created stressful working conditions that were clearly detrimental to the daily experience of the job itself. Unrelated to the pandemic, other participants discussed the ways in which a job can influence workers’ emotional and mental well-being. In a quality job, employees have a reasonable workload and find enjoyment in their day-to-day tasks. Employers offer opportunities for employees to challenge themselves through new projects while encouraging them to use their skillset to its fullest potential. Some participants also expressed a desire to help others or found fulfillment in jobs that allowed them to positively impact others and the community.

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTES RELATED TO ENGAGEMENT FROM WORKER VOICES PARTICIPANTS

A quality job is one in which I…

Enjoy the work and find it manageable

“So, about this time last year, I was actually leaving my job. Because, like I said before, I was able to work remotely. But because they did let a lot of other people go, everybody that stayed had, you know, double, triple whatever they had to do. And it was very, very stressful, you know. The situation itself was the workload, that it was more, I don’t know, more consistent.”

“In my case, I would like to complete a course, because I enjoy cooking and I would like to pursue that work sector that I like. I think it would be better for me to dedicate myself to something I like.”

“…[the pandemic] really changed my whole perspective on what it is to earn a living from top to bottom—because I used to do it because it was, like, what I needed to do to pay the bills or what I needed to do to, you know, put food on the table. And now it’s more like I need to do things that make me happy and don’t stress me out and don’t put me in a weird place mentally.”

Help other people or the community

“…[counseling’s] really given me the ability to display what I have intellectually. Yes, it gives me the ability to express what I have and to literally to help guide and mold people’s emotions.”

“So, for me, going into a job where I can also help people, especially with disabilities, that was very fulfilling to me.”

PROFESSIONAL GROWTH

While focus group participants discussed opportunities for professional growth as an element of job quality, the comments were not as prominent across transcripts as the five themes we identified. Instead, the desire for professional development was more commonly discussed as a personal endeavor pursued outside the workplace rather than as a necessary and important feature of a prospective job (e.g., “So, right now I’m looking for work, and I’ve been taking any class that I can take. Anything to upgrade my skills.”). Nevertheless, some participants mentioned taking part in professional development programs, valuing jobs that allowed them to grow their skills, and seeking employment that offered career paths and opportunities for advancement.

Concluding thoughts

In light of both the direct and indirect costs of employee turnover and vacancies (Boushey and Glynn 2012; Moon et al. 2022; Fuller and Raman 2022), employers have a strong financial incentive to both fill job openings quickly and retain productive workers under even normal economic conditions. And because there is no shortage of demand-side data, researchers and the general public alike are fully aware that the economic conditions following the COVID-19 recession were far from normal, characterized by a historically high number of job openings and an elevated quits rate. Surveys of businesses that provide this kind of insight, such as the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey administered by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, alongside real-time labor market information, including vast databases of online job postings, paint a fairly clear picture of the number and types of jobs that are open at any given time, in addition to the specific skills, education, and experience employers are seeking in their ideal hire.

We know much less about the supply side of the equation, however. What specific criteria are workers seeking in their ideal job? What does a quality job look like?

The conversations elicited by the Worker Voices Project give us unique insight into how a selection of noncollege workers would answer these questions as they emerged from a turbulent labor market and public health crisis. In the months and years preceding these focus groups, participants experienced a labor market characterized by the fear of catching a deadly virus and spreading it to their family members; workplaces in which they felt unsafe, unprotected, and unsupported; and generally difficult working conditions that sometimes involved being overworked. These workers discussed job quality as a multifaceted issue, one that begins with being adequately paid but encompasses much more. A worker with a quality job is also treated well, respected, and valued. They feel safe and secure, not constantly concerned about being laid off. There is flexibility around hours and location in order to attend to family and personal needs. A worker with a quality job likes their work and, rather than feeling stressed, feels challenged and fulfilled.

Conceptions of job quality shared by these workers align with many of the findings from prior research. Notably, the stability, predictability, and level of pay were important for focus group participants, just as they are identified as key ingredients of job quality in worker surveys (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019; Scott and Katz 2021; Maestas et al. 2017). Other areas of agreement include the importance of day-to-day work that is enjoyable, a job that is secure, work that provides a sense of purpose (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019), and a range of benefits being offered (Maestas et al. 2017). Consistent with worker surveys, career advancement as an element of a quality job did not arise as a top priority among focus group participants (Rothwell and Crabtree 2019; Maestas et al. 2017). Of note, focus group participants clearly articulated the importance of being treated well and feeling valued, issues that may fall under more general terms in the literature—such as “working conditions” (Figure 1) or “workplace relationships” in various other definitions—but are not always explicitly identified as dimensions of job quality.

There can be no single measure of job quality, as different workers value different things at different times in their lives. While the elements described in this brief may not be transferable to the broader population of noncollege workers from which focus group participants were drawn, we believe the findings in this brief accomplish three things nonetheless. First, for those wishing to improve job quality in a specific context or setting, the findings demonstrate the value of hearing directly from workers rather than applying an off-the-shelf definition that may miss the mark. Second, they serve as a starting point for such conversations, initiated by employers and professionals in the workforce development ecosystem who understand the linkage between worker well-being and business performance (Ton 2023). Finally, in conjunction with the lessons from worker surveys (Maestas et al. 2017; Rothwell and Crabtree 2019; Gallup, Inc. 2020), our findings provide a good foundation for future research examining how job quality elements are prioritized by different types of workers and job seekers, across settings, and over time.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve System or Fed Communities.

Please cite this work as: Dunne, Theresa, and Keith Wardrip. 2023. Worker Voices Special Brief: Perspectives on Job Quality. Fed Communities. https://doi.org/10.59695/20230925.

Media inquiries: Contact Daneil Mazone, Philadelphia Fed.

Research: Please direct inquiries about the research, data, and methodology in this report to Theresa Dunne.

Appendix: Methods

For this brief, we analyzed focus group transcripts using a combination of deductive and inductive methods to gain an understanding of how job quality was perceived and has been experienced by participants. Our analysis proceeded in three stages, and in each, we used NVivo (released in March 2020), a qualitative data analysis software, to organize and analyze our data. In the first stage, we familiarized ourselves with the extensive literature on job quality and developed a deductive codebook with codes capturing the elements of a quality job frequently discussed in the literature. Using this initial codebook, we identified all the material related to job quality in the 18 transcripts.

In the second stage, we selected from this material 312 statements that each conveyed a significant, explicit, and transparent sentiment or opinion related to job quality. Our determination of a statement’s significance was greatly informed by our initial reading of the literature. Some of these statements were participants’ reflections on the job they would like to have (e.g., “…an ideal job is a job that…”), but most were a recounting of personal experiences in the labor market (e.g., “…it was stressful working shorthanded…”). We ignored statements that were ambiguous or required too much in the way of interpretation.

In the third and final stage, we used thematic analysis to look for patterns in these significant statements and ultimately group them into the themes presented in this brief (Braun and Clarke 2006). We did so by open coding six transcripts and inductively developing a preliminary second codebook, informed by but not wedded to our prior reading of the literature. In applying this second codebook, we independently coded several transcripts, met to discuss any discrepancies, and made any necessary modifications to the codebook. For each code, we summarized the passages and looked for intersections and linkages across codes. This process allowed us to group statements on job quality into our primary themes and subthemes and to differentiate them from other issues that we highlight in this brief, including entrepreneurship and discrimination, which cut across multiple themes. Although it was not as recurrent in the transcripts as the primary themes, we call attention to the issue of professional growth because the topic was of importance to some focus group participants and garners significant attention in the literature; treating situations such as this separately “protects against the loss of these codes and against overstretching any themes in order to accommodate them” (Buetow 2010, p. 124).

To convey our findings, we present a summary of each individual theme, preceded by a structural description of the labor market as discussed by participants in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the opening and closing sections of the brief, we offer a composite description of job quality that combines these thematic and structural elements. In writing these sections, we were inspired by Creswell’s (2013) discussion of capturing the “essence” of a phenomenon in a composite description, characteristic of phenomenological studies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the focus group participants whose experiences and contributions formed the foundation for the Worker Voices Project, both generally and for this brief specifically. We would also like to thank the following people for their feedback and contributions to this brief.

Alaina Barca, Philadelphia Fed

Elizabeth Bogue, Atlanta Fed

Joe Budash, Philadelphia Fed

Sara Chaganti, Boston Fed

Deborah Diamond, Philadelphia Fed

Lei Ding, Philadelphia Fed

Eileen Divringi, Philadelphia Fed

Kyle Fee, Cleveland Fed

Rosemary Frasso, Thomas Jefferson University

Sloane Kaiser, Philadelphia Fed

Sarah Miller, Atlanta Fed

Merissa Piazza, Cleveland Fed

Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup

Theresa Singleton, Philadelphia Fed

References

Alpert, Daniel, Jeffrey Ferry, Robert C. Hockett, and Amir Khaleghiv. 2019. The U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Law School. ubwp.buffalo.edu/job-quality-index-jqi/.

Belardi, Susan, Angela Knox, and Chris F. Wright. 2023. “‘The Circle of Life’: The Role of Life Course in Understanding Job Quality.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 44(1): 47–67. doi.org/10.1177/0143831X211061185.

Boushey, Heather, and Sarah Jane Glynn. 2012. There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees. Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress. americanprogress.org/article/there-are-significant-business-costs-to-replacing-employees/.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101. doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brett, Daniel, and Tom Woelfel. 2016. Moving Beyond Job Creation: Defining and Measuring the Creation of Quality Jobs. San Francisco: Insight at Pacific Community Ventures. pacificcommunityventures.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2016/04/Quality-Jobs_Moving-Beyond-Job-Creation.pdf.

Buetow, Stephen. 2010. “Thematic Analysis and Its Reconceptualization as ‘Saliency Analysis.’” Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 15(2): 123–5. doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009081.

Clark, Andrew E. 2015. “What Makes a Good Job? Job Quality and Job Satisfaction.” IZA World of Labor, Article No. 215. doi.org/10.15185/izawol.215.

Congdon, William J., Molly M. Scott, Batia Katz, Pamela J. Loprest, Demetra Smith Nightingale, and Jessica Shakesprere. 2020. Understanding Good Jobs: A Review of Definitions and Evidence. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. urban.org/research/publication/understanding-good-jobs-review-definitions-and-evidence.

Cooke, Gordon B., Jimmy Donaghey, and Isik U. Zeytinoglu. 2013. “The Nuanced Nature of Work Quality: Evidence from Rural Newfoundland and Ireland.” Human Relations 66(4): 503–27. doi.org/10.1177/0018726712464802.

Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, Third Edition. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dawson, Steven L. 2018. “Now or Never: Heeding the Call of Labor Market Demand.” In Investing in America’s Workforce: Improving Outcomes for Workers and Employers, Vol. 2 Investing in Work, edited by Stuart Andreason, Todd Greene, Heath Prince, and Carle E. Van Horn. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Edwards, Roxanna, Lawrence S. Essien, and Michael Daniel Levinstein. 2022. “U.S. Labor Market Shows Improvement in 2021, but the COVID-19 Pandemic Continues to Weigh on the Economy.” Monthly Labor Review. Washington, D.C.: US Bureau of Labor Statistics. doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2022.16.

Fee, Kyle D. 2022. Does Job Quality Affect Occupational Mobility? Cleveland: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. doi.org/10.26509/frbc-cd-20220804.

Fuller, Joseph B., and Manjari Raman. 2022. Building from the Bottom Up: What Businesses Can Do to Strengthen the Bottom Line by Investing in Front-line Workers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=61928.

Gallup, Inc. 2020. The Characteristics of Good Jobs for Low-Income Workers. Washington, D.C.: Gallup, Inc. gallup.com/education/309911/characteristics-good-jobs-low-income-workers.aspx.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, American Sociological Association Rose Series in Sociology.

Knox, Angela, Chris Warhurst, Dennis Nickson, and Eli Dutton. 2015. “More than a Feeling: Using Hotel Room Attendants to Improve Understanding of Job Quality.” International Journal of Human Resource Management 26(12): 1547–67. doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.949818.

Leidner, Robin. 1993. Fast Food, Fast Talk: Service Work and the Routinization of Everyday Life. University of California Press.

Maestas, Nicole, Kathleen J. Mullen, David Powell, Till von Wachter, and Jeffrey B. Wenger. 2017. Working Conditions in the United States: Results of the 2015 American Working Conditions Survey. Santa Monica, CA:RAND Corporation. doi.org/10.7249/RR2014.

Miller, Sarah, Ashley Putnam, Merissa Piazza, and Kristen Broady. 2023. Worker Voices: Shifting Perspectives and Expectations on Employment. Fed Communities. doi.org/10.59695/20230524.

Moon, Ken, Prashant Loyalka, Patrick Bergemann, and Joshua Cohen. 2022. “The Hidden Cost of Worker Turnover: Attributing Product Reliability to the Turnover of Factory Workers.” Management Science 68(5): 3755–67. doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4311.

Muñoz de Bustillo, Rafael, Enrique Fernández-Macías, Fernando Esteve, and José-Ignacio Antón. 2011. “E Pluribus Unum? A Critical Survey of Job Quality Indicators.” Socio-Economic Review 9(3): 447–75. doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr005.

Osterman, Paul. 2017. Who Will Care for Us? Long-Term Care and the Long-Term Workforce. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Rothwell, Jonathan, and Steve Crabtree. 2019. Not Just a Job: New Evidence on the Quality of Work in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Gallup, Inc. gallup.com/education/267650/great-jobs-lumina-gates-omidyar-gallup-quality-download-report-2019.aspx.

Schudde, Lauren, and Kaitlin Bernell. 2019. “Educational Attainment and Nonwage Labor Market Returns in the United States.” AERA Open 5(3): 1–18. doi.org/10.1177/2332858419874056.

Scott, Molly M., and Batia Katz. 2021. What’s Important in a Job? An Analysis of What Matters and for Whom. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. urban.org/research/publication/whats-important-job-analysis-what-matters-and-whom.

Shakesprere, Jessica, Batia Katz, and Pamela Loprest. 2021. Racial Equity and Job Quality: Causes Behind Racial Disparities and Possibilities to Address Them. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. urban.org/research/publication/racial-equity-and-job-quality.

Ton, Zeynep. 2023. The Case for Good Jobs: How Great Companies Bring Dignity, Pay, and Meaning to Everyone’s Work. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2023. “Real Earnings – December 2022.” News release, January 12. bls.gov/news.release/archives/realer_01122023.htm.