appendiXes: Methodology, Demographics, Example Questions

Worker Voices: Shifting perspectives and expectations on employment

By Sarah Miller, Merissa Piazza, Ashley Putnam, Kristen Broady

May 24, 2023

Appendix A: Methodology

The Federal Reserve’s Worker Voices Project conducted focus groups with workers without a bachelor’s degree to supplement aggregate quantitative data that may not detail this population. Insights from job seekers and workers, especially those who are low- to moderate-income and who experience barriers to economic mobility, enhances the Federal Reserve’s understanding of the labor market and broader economic conditions to support its dual mandate of full employment and price stability. This was a qualitative study whose objective was to explore the experiences of workers and job seekers on how they navigated the labor market during the COVID-19 pandemic and afterward.

Research team

The Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta and Philadelphia led the project and partnered with each of the 12 Reserve Banks in the Federal Reserve System to conduct this research. The project secured Public Works Partners, a public and nonprofit sector community consulting and research firm, to select participants and facilitate focus groups with workers across the United States. Public Works Partners was secured as a third and neutral party to support this project for a few reasons: to mitigate selection bias, to provide neutral facilitation of discussion, and to coordinate logistics of the focus groups. The Federal Reserve research team consisted of project leads (Sarah Miller, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, and Ashley Putnam, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia), subject matter experts, and qualitative research analysts. The project protocols and methodology design were informed and guided by a Project Design Advisory Committee made up of various subject matter experts from a subset of the Federal Reserve Banks. Members of this group included community affairs officers, outreach specialists, labor economists, and qualitative research experts. Dr. Rosemary Frasso, visiting scholar with the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and a professor and program director of public health at Thomas Jefferson University, served as an advisor in development of the research design, coding, and analysis.

Qualitative research design

This research sought to investigate three sets of research questions:

- Why have workers without a bachelor’s degree made the decision to work, or not to work, during the pandemic? What has prevented people from returning to work or remaining in their jobs?

- What changes are workers without a bachelor’s degree trying to make in the current labor market to better their jobs or career opportunities? What priorities are influencing their actions?

- How are workers without a bachelor’s degree anticipating and preparing for their next transitions in the labor market? How has their employment experience during the pandemic impacted these future plans?

To answer the study’s research questions, focus group-based data collection and qualitative analysis methods were used to identify experiences, attitudes, and perceptions that influence worker behavior, as well as barriers and motivators for behavioral change.[1] An inductive approach was used to ask questions, identify themes, and find conclusions.[2]

To actuate this framework, we used focus groups as its qualitative methodology to understand the nuanced perspectives of job seekers and workers, especially those who are low- to moderate-income, their employment decisions during the pandemic and in the current labor market, and their next employment transitions. During these sessions, participants were asked semistructured questions from a facilitation guide about their experience with the labor market at the onset of the pandemic, their experience after the pandemic’s peak, and their perspective on work moving forward.

The creation of the facilitation guide was an iterative approach. Initial research questions and facilitation guide prompts were reviewed by workers and job seekers via two methods: One-on-one interviews were conducted with six workers to refine questions and prompts, and a pilot focus group session was conducted to aid in conversation facilitation and to ensure clarity of communication to participants. We conducted a pilot focus group in May 2022 to improve the facilitation guide and continued to refine and then finalized the guide after the first three focus groups. This final facilitation guide was used for 16 of the focus groups, but with subject-relevant questions added for three topic-focused sessions on job quality, challenges to rural communities, and wage and inflation pressures. Additionally, three of the 16 sessions were conducted exclusively in Spanish to reach the Latinx and Hispanic subgroups of the population, which have disproportionately high rates of workers in low-wage occupations, given their share of the workforce.[3] The facilitation guide design and recruitment followed “do no harm” expectations of ethical research standards, and participants had to have agreed to the informed consent before being placed in the candidate pool. An example facilitation guide can be found in Appendix C. This guide was translated for the facilitators conducting groups in Spanish.

A total of 20 virtual focus groups of 90 minutes each were conducted over the spring and summer of 2022. Focus groups were conducted virtually via Zoom, with a phone-in option, to increase the geographic diversity of participants, avoid health risks associated with in-person meetings, and decrease the travel burden for the research team. They were held after traditional working hours to minimize potential conflicts for participants.

Participant recruitment and selection

The research team employed a convenience sampling strategy and identified more than 60 community-based partners of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks to conduct recruitment. These organizations included community-based, worker-serving nonprofits (e.g., Goodwill, the United Way), job training providers, and workforce agencies or American Job Centers. Additionally, many individuals were referred by workers’ friends or family. Recruitment was conducted separately for each focus group, aside from the three topic-specific sessions (job quality, wages and inflation, and rural areas), in which participants were selected from existing qualified applicants who were recruited but not selected for earlier sessions.

Participant inclusion criteria included two factors: age (20–55 years old) and educational attainment (workers and job seekers with less than a bachelor’s degree). Age parameters were included as the study posed three research questions along a time horizon and asked for detail on employment experiences at the onset of the pandemic. The lower age bound for study participation was determined as 20 years old, presuming that those participants had a higher probability of working in the spring of 2020. The upper age bound was determined as 55 years old to engage with workers who have been actively navigating the labor market for a significant period. The study specifically focused on workers with less than a bachelor’s degree, since these workers are disproportionately affected by economic and labor market shocks, like those seen during the pandemic, and have greater precarity in employment generally.[4]

Selection of participants for each focus group started with partner organizations distributing project information, including the opportunity to earn a $75 gift card, to potential participants. Interested individuals completed an online questionnaire that included demographic information (including age and educational attainment) and an agreement to the informed consent. Public Works Partners selected individuals to invite to each session from the pool of eligible participants. Approximately 40 percent of the 1,243 survey respondents were eligible for participation, based on the qualifying criteria of age and education. For the first 10 focus groups and the topic-specific sessions, participant selection was designed to reflect the demographics of those who filled out the survey for that session. For the final 10 sessions, Public Works Partners prioritized demographics that were underrepresented in the first 10 sessions; these groups included young men, people of color, Native Americans, and those living in rural areas. The topic-specific session on job quality prioritized individuals from industries likely to have organized labor, and the rural session prioritized Native Americans and individuals from rural areas.

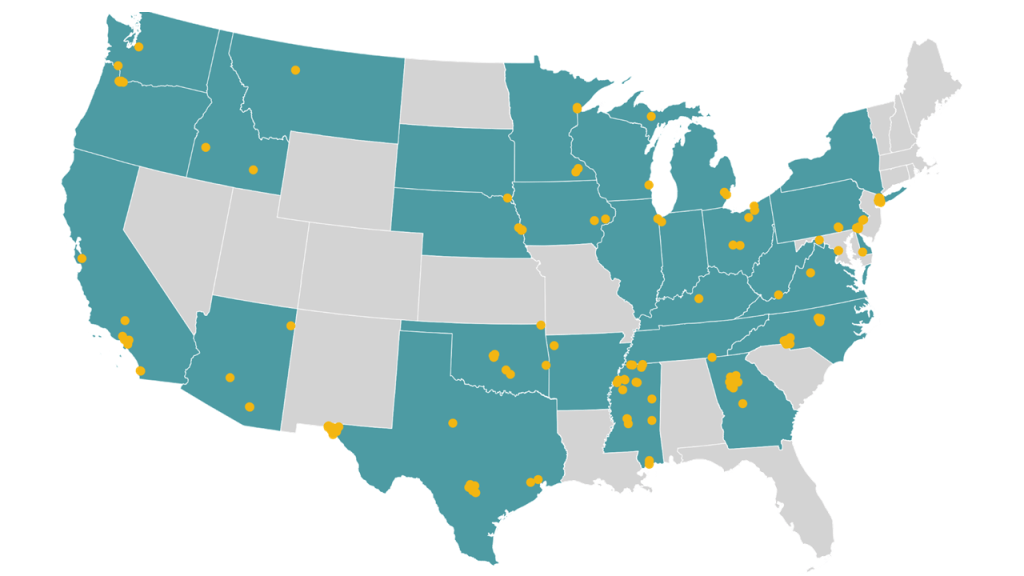

A total of 289 respondents were invited to the 20 sessions to achieve a total of 175 participants. On average, 14 respondents were invited to each session, and on average, nine participants participated in each session. Focus group participants were drawn from 33 states and 147 zip codes across the United States in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Participants had diverse racial, ethnic, educational, and family backgrounds. Fifty-eight percent of participants identified as caregivers, and 60 percent identified as being employed. Analysis in this study represents input from 168 participants in the 19 focus group sessions conducted following the pilot. Expanded participant demographic information can be found in Appendix B.

Participants were provided an individualized Zoom link to associate them with the demographic information they provided in the screening questionnaire. At the beginning of each session, the Federal Reserve team presented slides on the project’s purpose, recording, confidentiality, and informed consent, Zoom tips, focus group etiquette, and gift card disbursal. Public Works Partners shared participant demographic data and preliminary insights after each focus group to the Federal Reserve research team.

Focus group transcript coding and analysis

To analyze the qualitative data, the coding team used the pilot focus group transcript to employ an inductive coding approach, in which codes were created and then themes emerged.[5] First, the coding team employed open coding to identify topics, themes, and an initial set of codes. To test the code definitions and increase intercoder reliability, multiple coders coded the first focus group transcript and then compared outcomes. Adjustments were made as needed. From there, analysts used selective coding to analyze group codes into categories, then themes, respectively.[6] Next, they used an iterative approach to define specific codes for the final code book as they reviewed subsequent focus groups.

The codebook was developed by Federal Reserve System analysts from the transcripts to include broad themes, definitions, examples, and relevant subcodes. Themes derived from the transcript data that were included as high-level (“parent”) codes in the codebook include: (1) barriers to employment, (2) job quality, (3) increases in mental health concerns, (4) changes in preferred employment characteristics, (5) improved employment opportunities or financial stability, (6) system/government interactions, and (7) resources and networking.

A larger number of subcodes (“child” codes) were developed to further analyze content pertaining to secondary themes within each high-level theme. Using the code book, the coding team coded subsequent transcripts independently and then jointly reviewed to validate codes to increase intercoder reliability. Analysts and coders had access to video and audio recordings as well as transcripts that were transcribed by CaptionSync. An analysis of all transcripts was conducted by the authors of this report, the coding team, and the research team. The coding team, authors, and analysts worked directly with the code transcripts to examine overlap of codes, quotes within individual codes, and language used to describe themes.

Community-based participatory research principles

Workers were engaged throughout the research design and implementation process. Workers offered insights to improve the screening questionnaire used to source focus group participants, to help iterate on the facilitation guide used in each focus group, and to validate research findings to ensure framing and language use resonated. Individual interviews were conducted at the onset of project design to test and refine research questions and to inform the semistructured focus group protocol. These conversations helped the research team reframe questions, reduce bias or leading elements in questions, and learn how participants would hear and respond to certain prompts. A pilot focus group was conducted to help improve how the conversation was facilitated, to refine flow and structure of questions, and to reduce administrative barriers from the screening questionnaire and improve guidance on technology access to join the virtual focus groups.

To validate findings from this research, three additional focus groups were held with a subset of workers initially engaged. These conversations shared topline findings and summaries from themes to confirm that the qualitative processes employed resulted in an accurate reflection of participant sentiment and perspectives from the 2022 discussions. These conversations also informed certain language and word use in this report. For example, we use workers in low-wage roles as opposed to low-wage workers. These conversations allowed for a confirmation on findings and to ensure language was respectful and reflective of their perspectives.

Additionally, two community-based organizations focused on workforce development and wraparound supports for workers and job seekers were engaged to provide a review of this paper. Their review focused on ensuring we were comprehensive in framing issues their participants experienced and that language and phrasing used were appropriate and respectful of the realities of these workers and job seekers.

Limitations

It is important to discuss the biases and limitations that are important for the reader to keep in mind when interpreting these findings. First, there is a tradeoff in research from conducting qualitative research to gain nuanced insight into the subject matter, knowing these results may not be generalizable to the broader population. The research team acknowledges these limitations, but through qualitative research techniques and coding, there are overall themes that can be considered.

Second, this project employed a convenience sampling strategy that used community-based organizations to conduct recruitment. Selection bias occurred because individuals who received the demographic screening questionnaire were connected to those community-based organizations, workforce development agencies, and training providers, and were therefore connected to the workforce system in some way; this could upwardly bias selection toward those who are unemployed and would disproportionately have higher barriers to employment in the labor market than a standard sample of the workforce. This population is more likely to be participating in training and more likely to be actively engaged in a career change or job search. Given inclusion criteria for worker age, the results of research reflect those of close to prime-age working status and do not delve into barriers to employment affecting exclusively youth or older workers in the labor market.

Finally, by using virtual focus groups, this study has limitations on gathering insights from workers or job seekers with barriers to broadband access or digital devices, since an email address was required to complete the demographic questionnaire, access the individualized session participation link, and receive the participant incentive. This method of data collection and dissemination excluded individuals who did not have email addresses, which results in response bias in the sample. As needed, participants were provided a phone number to dial into the session to participate in the focus group.

Appendix B: Participant demographic information

Of the 175 focus group participants, 58% identify as female, 40% identify as male, and 2% identify as transgender, gender nonconforming, or did not answer. Their ages range from 20 to 55 years old, with 22% ages 20–24, 40% ages 25–34, 25% ages 35–44, and 13% ages 45–55.

Focus group participants were drawn from 33 states and 147 zip codes across the United States, with 54% residing in urban communities, 29% in suburban communities, and 17% in rural communities.

Of 175 participants, 58% identify as caregivers. Of 102 caregivers, 68% are responsible for one or two people and 32% are responsible for three or more people.

Among 102 caregivers, there were 87 total instances of individuals having at least one child in their care (65%) and 46 total instances of having a parent(s) or grandparent(s) in their care (35%).

Of 175 participants, 63% identify as Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish when asked about race. When asked about ethnicity, 48% identify as Black or African American, 29% identify as white, 8% identify as with an Indigenous group, and 1% identify as Asian or Asian American. Additionally, 6% are self-described or preferred not to answer and 8% identify with multiple races. Participants could select more than one answer for ethnicity.

Nearly half (46%) of the participants attended some college, 11% earned an associate’s degree, 27% earned a high school or high school equivalent degree, and 14% attended some high school, while only 2% earned a foreign degree.

A majority of participants (77%) attended alternative education programs. Of these 134 participants, 54% participated in a noncollege training or workforce program; 53% participated in a trade, technical, or vocational program; and 33% participated in an apprenticeship program.

Of 175 participants, 60% are employed. Of the 105 who reported they were employed, 62% work full-time, 28% are self-employed, and 28% work multiple jobs.

Appendix C: Example facilitation questions

Looking back: Onset of the pandemic (15 minutes)

- We want to learn a little bit about your experience with work at the start of the pandemic. How would you describe your job during this time? For folks who stopped working, tell us more about how you navigated that.

- How did your employer’s treatment of its employees influence your decision to remain in your role, seek a new job, or stop working altogether?

- For those of you who are parents or maybe take care of a family member, how did that influence your decisions around work (March–May 2020)?

- Did anyone start working for an app like Uber, Lyft, Taskrabbit, DoorDash? What was that experience like, and why did you make this shift?

- Did anyone start working for themselves or start their own business?

- Did anyone take time during the pandemic to learn new skills or go back to school?

Current changes in labor market: June 2020–Present (20 minutes)

- Did you have a shift in perspective around work? What factors influenced your shift in perspective?

- We know that as the pandemic progressed, many people made the decision to change jobs. Did that happen to anyone here today? Tell us more about why you changed jobs.

- We have also heard many employers have changed what they are looking for in terms of hiring. Have you experienced this?

- Did you find that stimulus checks, unemployment insurance, gave you more flexibility in jobs or training? Did this additional support impact your decisions around work? If so, how?

Moving forward: Looking to the future (15 minutes)

- How has working during the COVID-19 pandemic affected your perspective on work going forward? How have your priorities shifted?

- Looking forward, do you feel more compelled to start your own venture or work for yourself?

- Does anyone see themselves pursuing a role that is out of your comfort zone?

- Do you want to pursue additional training/education to build your skills?

- For those pursuing jobs or planning to pursue a new job, how are you hearing about these opportunities?

- Did the skills you gained over the course of the pandemic enable you to pursue a new job?

Endnotes

[1] Morgan and Krueger, The Focus Group Guidebook; Gibbs, Analyzing Qualitative Data.

[2] John W. Creswell and Cheryl N. Poth, 2018, Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, Los Angeles: Sage Publications; Barney G. Glaser, and Anselm L. Strauss, 1967, The Discovery of Grounded Theory, New Brunswick, NJ: AldineTransaction.

[3] Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman, 2019, Meet the Low Wage Workforce, Washington, D.C.: Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings. brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/201911_Brookings-Metro_low-wage-workforce_Ross-Bateman.pdf

[4] Tyler Boesch, Alene Tchourumoff, and Ryan Nunn, 2022, Occupational Segregation Left Workers of Color Especially Vulnerable to COVID-19 Job Losses,” Minneapolis: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/occupational-segregation-left-workers-of-color-especially-vulnerable-to-covid-19-job-losses; Elise Gould and Melat Kassa, 2021, Low-Wage, Low-Hours Workers Were Hit Hardest in the COVID-19 Recession, Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute. epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/

[5] M. Ariel Cascio, Eunlye Lee, Nicole Vaudrin, and Darcy A. Freedman, 2019, “A Team-Based Approach to Open Coding: Considerations for Creating Intercoder Consensus,” Field Methods, 31(2): 116–30. doi.org/10.1177/1525822X19838237

[6] Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie, Wendy B. Dickinson, Nancy L. Leech, and Annmarie G. Zoran, 2009, “A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research,” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 83): 1–21.