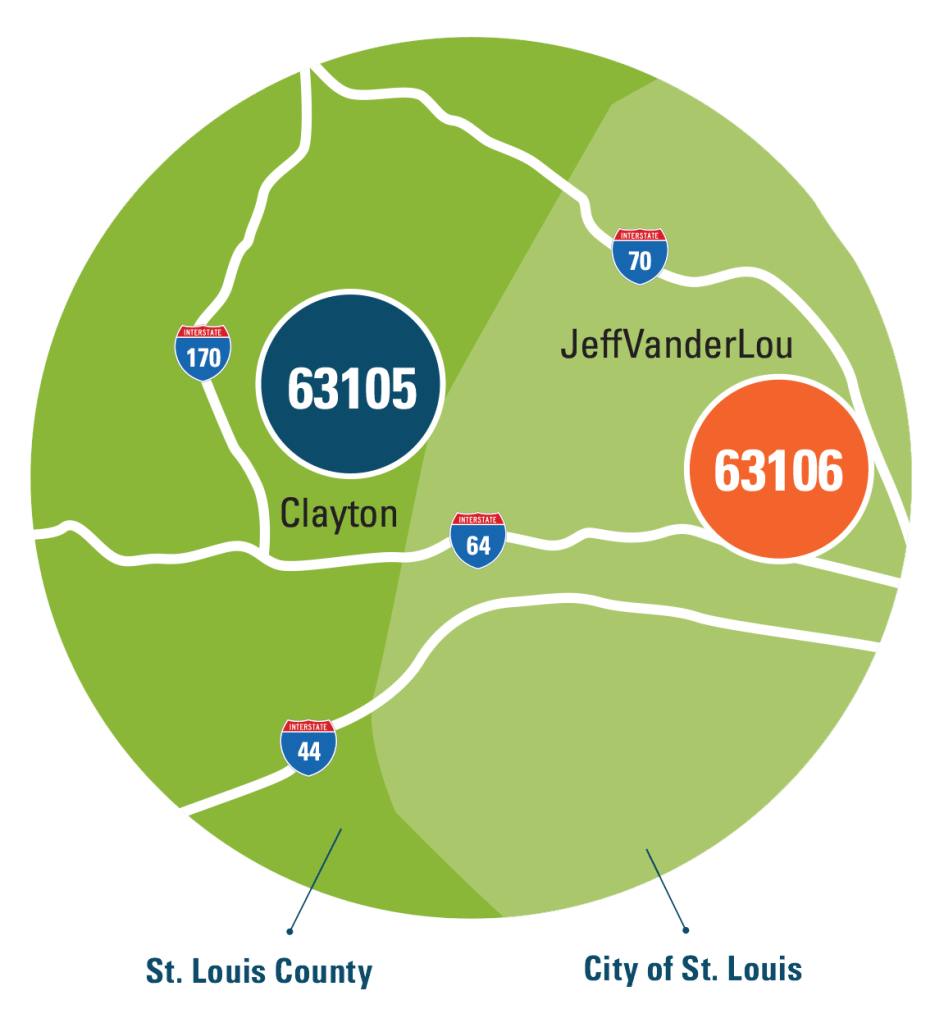

It’s just a street. That’s all. A normal street running east and west through the heart of St. Louis. There’s no wall, no guard towers, no razor wire, no soldiers patrolling like Berlin in the 1960s. But which side of this four-lane road you live on can have an enormous impact on your life—including how long it lasts.

That is the power of Delmar Boulevard.

Tamika Staten was born and lived much of her childhood north of Delmar, and North St. Louis City is where her “mom, grandma, and great-grandma were raised,” she said. “North St. Louis will always have a special place in my heart. A lot of people look at North St. Louis and see a poverty-stricken area with dilapidated homes and abandoned businesses. I see all of my childhood memories and a bunch of neighbors from the same background as me. I love North St. Louis City, and I serve it proudly.”

North of Delmar Boulevard is home to most of the city’s Black history. For generations it was the only place in St. Louis open to people of color. Black Americans, many of them formerly enslaved, fled the Jim Crow South during the Great Migration. Those who made it to St. Louis slammed into a figurative wall, which came to be called the Delmar Divide. It was created by a real estate industry, controlled by white people, who used racial covenants and steering to push Black people north of Delmar and white people to the south of it. Left with no other choice, Black residents settled in North St. Louis.

More than settle, they thrived.

They created businesses and joined professions and built stately brick Victorian homes for their families. Then came the 1930s, when banks began using redlining to deny mortgages to prospective borrowers in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The same story played out in cities around the country with the same ugly results.

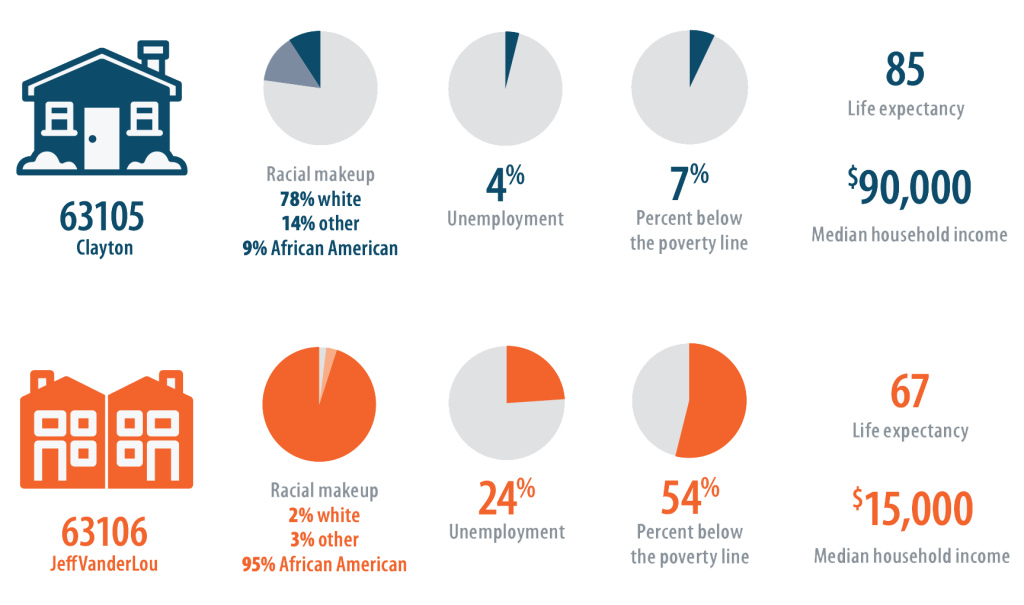

Today, most of the vacant lots in St. Louis City are concentrated north of Delmar. Redlining policies have contributed to broader inequities as well. A 2018 study by Washington University found that 95 percent of residents living in the 63106 ZIP code in North St. Louis City are Black, 24 percent of residents are unemployed, and 54 percent live below the poverty line, with a $15,000 median household income and a life expectancy of 67 years. In the 63105 ZIP code, just 10 miles away in the St. Louis County suburb of Clayton, 78 percent of residents are white, 4 percent are unemployed, and 7 percent live below the poverty line, with a median household income of $90,000 and a life expectancy of 85 years.

“…it feels really good helping somebody from the community I’m from.”

-Tamika Staten

Growing up as the middle child in the family, Staten wore hand-me-downs from her larger older sister. Nothing fit. She felt embarrassed. “It’s hard to learn and focus on your work when you’re worried about if somebody is going to pick on you,” Staten said. Senior year, she went to school full time while working two jobs. “I spent everything I had. My clothes were cute, but I didn’t have a car and I didn’t have savings.”

In 2014, when she was 25, Staten began work as a teller at a credit union. One day, a customer came to her window to make a deposit. She was shocked by his account balance, which was much larger than what she normally saw. She thought maybe someone had left him insurance money, but she noted there was no single large deposit. Instead, the man paid himself $200 every two weeks. “I got my feelings hurt when I saw that somebody else had the nerve to have money and I didn’t,” Staten said. “I smiled and finished his transaction, then I closed my window, took a break, and went outside to my car and cried. I had $13 in my checking account. I had a savings account, but it was purely decorative.”

The experience lit a fire.

Staten wanted a house for herself and her son. Nobody in her immediate family owned a home, and her credit score was dismal. Staten sought advice from a banker and did her own research.

Over the course of seven months, “I built my credit up from 570 to 744,” she said, and bought a one-story three-bedroom house in Florissant, a suburb in North St. Louis County. “My son and I sit in the back yard and roast marshmallows,” she said. “I’m saving more money than I’ve ever been able to save, and all because I got my feelings hurt.” Staten, now 32, felt driven to help others achieve what she’d achieved. Her managers moved her over to Prosperity Connection as a financial education coach. The nonprofit affiliate of the credit union provides financial literacy and credit coaching service.

Tamika Staten teaches a financial planning class for clients of Prosperity Connection.

When Eddie, a new client, arrived at Staten’s office she felt an immediate bond. Eddie was from North St. Louis, too, and he needed help. He’d maxed out his credit cards, had loan debt to his bank and unpaid medical bills in collection, and owed a friend several thousand dollars. Eddie, who is about 40, had three jobs, but he was still drowning.

On top of that, his ancient car appeared near death, and his credit union had just turned him down for an auto loan in language that was very direct. “He went home and cried about it,” Staten said. Fortunately, the loan officer didn’t just say “no.” He referred Eddie to St. Louis Builds Credit (STLBC), which connected him with Prosperity Connection—and to Staten, who understood how poverty felt. She shared the story of her own financial journey with Eddie.

When Eddie arrived, Staten helped him create a budgeting regimen. Eddie began working on improving his credit, checking in with Staten for advice and suggestions. “He sent me monthly ‘personal finance reports’ of his progress in paying down his debt,” she said.

Within a year, Eddie had transformed his finances. His credit score is 725, up from the low 500s. He has no personal loan debt, very little credit card debt, and the beginnings of some savings. Best of all, when he returned to the credit union that had initially turned him down, he signed for a car loan at the lender’s lowest rate at the time.

“None of us can pull ourselves out of the cycle of poverty without help,” Staten said. “Eddie came from where I’m from. He had the initiative to keep working and to keep pushing.”

Eddie reaches out occasionally to let her know how he’s doing. Staten is confident he will be financially stable. “I love that for anybody, but it feels really good helping somebody from the community I’m from,” she said.

New ideas to help Eddie and others

Urban Institute researchers estimate that 30 percent, or about 68 million, of American adults had debt in collections in 2019, even before the pandemic forced millions of people out of work. By the time a debt reaches a collection agency, it’s more than 180 days past due and can be reported to credit bureaus. This succession of events can damage a person’s credit score and lead to higher credit costs, reduced access to jobs, and more.

The nation’s credit system can be harsh on anyone with little savings, a circumstance that characterizes many. According to Fed research, 36 percent of Americans would have difficulty paying an emergency expense of even $400.

While credit scores don’t use race as a factor, the long-term impact of redlining and the way in which scores are determined, such as not including rent and utility payments as a means of an individual’s establishing a payment history, often lead to Black Americans having lower credit scores than white Americans.

Efforts to bolster the credit standing of residents in low- and middle-income (LMI) communities in St. Louis, particularly minority residents, received a boost in 2019. David Stiffler served as the president of the Equifax Foundation and a funder of Prosperity Connection. Stiffler approached Prosperity Connection’s then-executive director, Paul Woodruff, with an idea: Would Prosperity Connection be willing to expand beyond its scope of providing credit counseling in order to serve as the backbone organization to build a citywide movement for financial health?

The effort would be patterned on Boston Builds Credit (BBC), a nonprofit founded in 2017 and also funded by Equifax. BBC supports credit-building programs, conducts informational campaigns, and advocates on financial issues that affect LMI communities. A person, household, or community is LMI if income is below 80 percent of an area’s median income.

“David said, ‘You might do this,’” Woodruff said. “It was an invitation from our funder to look at a different level of impact.”

BBC works with partners, including banks, to connect residents to credit-repair services. If someone with a low credit score is turned down for a loan, the bank then guides them towards help—workshops, credit counseling sessions, and one-on-one financial coaching—to help them get a “yes” the next time they apply. The client, who must do the hard work of budgeting and saving, gets support from BBC and its partners. The project also works with credit bureaus, financial institutions, and policymakers to encourage safe financial products and consumer protections. For example, its legislative priorities include a bill to regulate the use of credit reports by employers.

To start a similar effort in St. Louis, Woodruff convened other organizations that help people improve their financial health. “We had to approach this in a collective fashion,” he said. “The Boston model is built on partnerships across geographic areas.” The partners agreed to launch St. Louis Builds Credit (STLBC) as a pilot project in the Gravois-Jefferson Corridor in St. Louis City in 2020.

The Equifax Foundation provided money to help get STLBC off the ground, but the project required more financial support. Woodruff had heard about a program called Investment Connection. Events held by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis saw nonprofits pitching their programs to a room full of bankers and other prospective funders.

He decided to submit a proposal.

Paul Woodruff’s proposal for St. Louis Builds Credit was 1 of 10 chosen for a 2019 Investment Connection event sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Building bridges between banks and CRA-eligible programs

Since the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) passed in 1977, banks have been encouraged to lend throughout their communities, including in LMI communities. The CRA was a response to redlining, the discriminatory pattern of denying credit based solely on the ethnic or racial composition of certain communities.

Banks and financial institutions provide support to community organizations through loans, investments and grants, and technical services. To receive CRA consideration, a bank must be able to show that support for a particular project meets the needs of the communities within which it operates. Bank examiners from regulating agencies such as the Federal Reserve System review each activity to determine if, in fact, the bank’s activity is eligible for CRA credit. If it is, the CRA credit is applied to a bank’s overall CRA rating, which can range from “outstanding” to “substantial noncompliance.”

A bank needs a positive CRA rating to take certain actions, such as opening a new branch. Banks have tended to be risk averse in picking CRA-eligible projects, leaning towards activities, loans, or investments that have counted for CRA purposes in the past and avoiding those outside of their regular areas of business. Investment Connection is intended to “expand the pie” of CRA funding by encouraging new, innovative ways for bankers to support the communities they serve.

Investment Connection, now offered by 8 of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks, serves many functions. The program builds a bridge between nonprofits and banks seeking CRA-eligible projects. It teaches nonprofits about the CRA and what bankers are looking for in those projects. It identifies for banks an array of CRA-related needs in the community. Philanthropies and governments also participate, helping to connect bankers and the larger funding community, and facilitating additional collaboration on the funding side.

Paul Woodruff and Sara Middendorf answer funder questions during the “speed dating” period at Investment Connection. Woodruff was then-director of St. Louis Builds Credit; Middendorf is the current program manager.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City started Investment Connection in 2011. Community development team members saw that bank portfolios were concentrated in a narrow range of projects and heard that nonprofits were having a hard time connecting with financial institutions. They decided a bridge would help. The Kansas City Fed loosely modeled its Investment Connection events on the Shark Tank program, an American reality television series where entrepreneurs pitch their ideas to a panel of investors.

Ten years after holding the first Investment Connection event, the Kansas City Fed can trace more than $52 million in loans, investments and grants, and technical services to Investment Connection. That amount is more than $60 million for the eight participating Reserve Banks.

The St. Louis Fed was the first Reserve Bank to adopt the model Kansas City developed. Since 2017, St. Louis has held events in seven cities. These events have yielded $2,726,020 in grants, loans, and investments for community and economic development projects.

Before the event convened in October 2019, similar to its other Investment Connection events, the St. Louis Fed reached out to banks and nonprofits, conducted training on the CRA, and requested proposals for funding. St. Louis Fed examiners vetted all proposals to be sure they appeared eligible for CRA credit. Organizers chose 10 proposals they felt were the strongest, and they invited representatives from the organizations that made these proposals to pitch their ideas for investments to bankers, philanthropies, and government officials invited by the Reserve Bank.

Paul Woodruff’s proposal to invest in the STLBC program was among those that made the cut. Now it was time for him to make the pitch.

Foundations of trust

Each Reserve Bank organizes its Investment Connection events a little differently. The St. Louis Fed includes pitches, informational posters about the nonprofit, and brief meetings akin to speed dating. To Woodruff, the event felt less like Shark Tank and more like Love Connection, the long-running television dating game show in which individuals attempted to connect with a compatible partner.

“It really is a courtship process,” Woodruff said. “We could have the best pitch in the world, but the reality is that you have to have strong relationships between organizations. You don’t only have to have the great idea, but you also have to have trust.”

The pitch comes first

Those making a pitch stand on stage in front of a few dozen bankers and other funders and have a few short minutes to make a case. In order to get funding, they must demonstrate their credibility and show that their organization is financially sound and their program is transformational. The stakes are high. Many people would be terrified. But Paul Woodruff is not “many people.”

“I kind of relish these opportunities,” he said. Woodruff is a former parliamentary debater with a background in theater. “Win, lose, or draw, it was a great chance to showcase the new program. And it was really awesome to see peers and colleagues talk about what they do in a way that we typically don’t.”

Sometimes, Woodruff and others said, nonprofits approach bankers with the attitude that they deserve support just because their organization is doing good work in the community. Investment Connection encourages nonprofits to think more broadly, and to look for and highlight what both the nonprofits and the banks have to gain.

“Banks and nonprofits need mutually beneficial relationships,” Woodruff said. “We can’t just go with our hand out [for a donation]; we need an attitude and expectation that we have to deliver. If we approach the work understanding there has to be mutual benefit, we could get to solutions a little faster.”

Stacy Clay agrees with Woodruff’s thinking

Stacy Clay is director of community affairs with First Bank, a family-owned bank that has served the St. Louis metro area for more than 100 years. He attended the Investment Connection event where Woodruff made his pitch. While Clay says it’s personally satisfying to see the results of CRA-related investments, that’s not the goal.

“It’s not my money,” he said. “We want to be able to say to our senior leadership, ‘Here’s what the investment has yielded.’”

Before joining First Bank, Clay was deputy superintendent for the St. Louis Public Schools, a large urban school system. Before that, he directed a college-access nonprofit called College Summit and taught kindergarten and first-grade students.

“I understood the link between strong communities, strong families, and strong people”

–Stacy Clay

“I understood the link between strong communities, strong families, and strong people. It’s hard to get a strong, healthy student coming out of a rundown, dilapidated environment. These characteristics are bundled, they just are.” The 18-year gap between the life expectancy of residents in North St. Louis and Clayton is just one example.

In the case of STLBC, what impressed Clay was the chance to change the credit system, which determines how credit scores are assigned and used. Clay appreciated that Woodruff’s pitch for STLBC didn’t just talk about providing a new pathway to credit counseling. Instead, Woodruff talked about a community-wide movement to improve credit health, something that could improve credit scores of individuals and, at the same time, reduce income inequality and the racial wealth gap.

According to figures provided by the St. Louis Fed, there is a distinct racial wealth gap in St. Louis when housing values are used as a proxy for wealth. In St. Louis City, the median house value for white residents is $170,000. For Black residents, the median house value is $65,000. In St. Louis County, the median house value for white residents is $250,000. For Black residents, the median house value is $100,000, according to the American Community Survey, 1-year estimates for 2019.

First Bank’s Clay said that his employer looked for CRA-eligible investments that would benefit the individual and also have an impact on the credit system.

“St. Louis Builds Credit was positioning itself to do individual credit counseling so John Smith can get his credit score up to buy a house,” he said. “They were also looking at the system, and how we build a program so we’re having an impact on John Smith and Jane Smith and Sally Jones and all these folks. That was very intriguing to us and something we wanted to support.”

Clay was impressed with Woodruff’s proposal. He reached out with an offer of $50,000 paid over two years. The two entered into a service agreement that involves a credit coach with STLBC and a First Bank loan officer working with bank customers to help them improve their credit scores to the point that they’re eligible for a small business or mortgage loan.

Investment Connection was the agent that brought the two together.

Woodruff appreciates that Investment Connection provided a high-profile platform to spread the word about his group’s regional effort to build residents’ financial health. The Fed’s program gave STLBC an opportunity to highlight the importance of credit in improving the financial condition of people and businesses in LMI communities. “It was part of that process of moving from the STLBC coalition to the larger community,” he said. First Bank, he added, was the first financial institution to go all in to support STLBC.

Clay now serves on the organization’s steering committee. He said that his level of involvement was a direct result of Investment Connection. “St. Louis Builds Credit was a new program,” he said. “While most people in the room knew of Prosperity Connection, they had not heard of this program.”

Which means the Investment Connection event did exactly what it was intended to do.

Ariel Cisneros, a senior advisor with the Kansas City Fed and founder of Investment Connection, emcees an Investment Connection event.

Investment Connection grows from its beginnings in Kansas City Fed

Examiners at all 12 Federal Reserve Banks conduct CRA evaluations. A decade ago, Kansas City Fed officials overseeing that work reached out to their colleagues in the Bank’s Community Development Department asking for help. Ariel Cisneros, a community development advisor at the Denver branch, responded to the request. “[The examiners] were seeing a lot of banks whose portfolios of CRA activities were very focused on the affordable housing space,” Cisneros said. “They asked, ‘Can you help us to diversify, to help the banks’ CRA officers understand the breadth of CRA opportunities that are out there?’”

Examiners wanted to reduce concentrations of risk by spreading loans and investments into areas beyond housing. They had a broader goal, too. “It was also about the fact that the banks’ CRA officers are supposed to look at the needs in the community,” Cisneros said. “You can put 100 percent into affordable housing, but wouldn’t it be great to show your CRA examiner and your community that you’re in tune with them by meeting diverse community needs?”

Cisneros and his boss, Tammy Edwards, senior vice president of the Community Engagement and Inclusion Division, met at the Kansas City Fed’s Denver branch office. They found a meeting room, shut the door, and didn’t leave until they had developed a framework for a new program to support diversified use of the CRA. The program they shaped as Investment Connection offered three elements:

- Information for nonprofits about the CRA and what banks were seeking.

- Proposals pre-vetted for CRA eligibility by the Kansas City Fed’s examiners.

- An opportunity for banks and other prospective funders to hear pitches from up to 10 nonprofits with vetted proposals. Later, the Kansas City Fed added a searchable online database to make all vetted proposals available to funders.

After that, Cisneros said, “I talked with community groups and funders to ask, ‘What do you think of testing it?’” He held the first Investment Connection event in Denver in the fall of 2011. Since then, the Kansas City Fed has held some 60 Investment Connection events that matched more than $52 million from funders with CRA-eligible projects in the Kansas City District. Cisneros, the founder of Investment Connection, leads a working group of staff members from Reserve Banks that use the program.

Seven other Reserve Banks have adopted the Investment Connection model, often tailoring the program to unique circumstances in their parts of the country. These seven are Atlanta, Cleveland, Dallas, Minneapolis, New York, Richmond, and St. Louis.

Ariel Cisneros chats with Lisa Bloomquist, executive director of HomesFund (left), and Evelyn Lim, at the time the regional administrator for the HUD Rocky Mountain Region, at an Investment Connection event in Denver.

Pre-vetted proposals make it easier for banks to diversify investments

When a bank considers investing in a project for CRA credit, its CRA officer vets both the nonprofit organization and the proposal. This preliminary process for assessing CRA creditworthiness can take hours for a single proposal. Even then, the bank doesn’t know for sure if an investment will receive CRA credit until the examiner arrives to do the evaluation, which could be as much as five years later. If the examiner finds the activity ineligible, if the activity is large enough, it could result in a negative CRA rating, even if the activity itself was good for the community.

Investment Connection flips that process around. CRA examiners vet organizations and proposals before banks invest, reducing the risk they take in committing time and money to a project.

“The idea that we would have an audience with nonprofit partners [already] vetted by the Fed was very exciting and intriguing to us at First Bank,” said Stacy Clay, the bank’s director of community affairs. “We’re a midsized bank, and we don’t have the community development personnel to rigorously vet every nonprofit partner. The fact that the Fed had done that [diligence], and [the nonprofit] had met some fairly high standards, gave us a lot of comfort.”

Jim Enright, a senior bank examiner with the Kansas City Fed, was the first examiner to work with Cisneros to test the new Investment Connection model. He has since reviewed almost all of the nearly 1,500 proposals submitted in the Kansas City Fed District since 2011. Enright likes that CRA rules offer flexibility by recognizing that a bank’s performance varies based on the markets that they are in. “[Evaluating the performance of a bank is] a gray area, it’s not black and white. It really forces the examiner to use their judgment in evaluating an institution.” The rules recognize that one bank differs from another bank in another part of the state or country. “But the banks also want metrics and hard-and-fast rules, so they know they’re going to get credit for certain activities,” Enright said.

That subjective element of the regulation is the reason why no Reserve Bank will guarantee that an Investment Connection activity will receive CRA credit. Instead, the Reserve Banks offer a yay or nay on whether the proposal appears eligible. Proposals on the bubble don’t get moved forward.

“If the CRA examiner says ‘no,’ then you don’t put it on the Investment Connection website,” said Cisneros. “There’s a lot on the line. If a bank makes a loan or investment and they don’t get credit, that could come back to bite us. But that hasn’t happened. We take it seriously, that review.”

An organization does not have to be one of the presenters at an Investment Connection event to benefit from the CRA review. Once its proposal is vetted and placed on the Investment Connection website, the organization is free to shop it around to banks, and banks can search the website for vetted projects at any time.

Sharks don’t always take the bait

If there is one frustration for the eight Reserve Banks that sponsor Investment Connection events, it’s that most of the organizations presenting proposals do not get funding. Cisneros found that prior to the pandemic, 30 percent of Kansas City Fed presenters got funding after an in-person Investment Connection event.

“If you’re in the venture capital or angel investor space, they’re not going to fund every proposal that they see,” Cisneros said. Still, the opportunity for presenters to share information about their organizations with many potential funders at one time can yield a meaningful payoff. “If you do get a bite,” Cisneros notes, “your return on investment is quite high.”

In 2020, the pandemic forced events online. While a virtual Investment Connection event can pull more funders from around a state or district, it lacks the collegial feel of in-person events, during which funders encourage peers to support a favorite project and where presenters can chat informally with funders. Some Reserve Banks say they’ve been disappointed in the funder response to virtual Investment Connection events.

Even before the pandemic, Reserve Banks were looking at ways to structure the program to boost the chances that presenters would receive funding.

All Reserve Banks provide coaching and information for presenters, helping them speak to the specific needs of bankers. Some Reserve Banks have narrowed the geographic scope to areas of greatest need or where the community appears particularly ready. Others have held Investment Connection events in rural areas, where bankers have more trouble finding investments. The Cleveland Fed, for example, held events in Slade, Kentucky, and Nelsonville, Ohio.

The St. Louis Fed has used regular evaluations and surveys to help it structure the program for nonprofits and bankers to achieve maximum impact.

Lauren Hornett, vice president of community development at Wells Fargo (left) talks with Liddy Romero, CEO and founder, WorkLife Partnership, at an Investment Connection event at the Kansas City Fed’s Denver Branch.

St. Louis Fed measures progress, adds to the Investment Connection model

Neelu Panth brought a background in social work and program evaluation to her work with the St. Louis Fed, and she applied it to Investment Connection. When the St. Louis Fed adopted the program in 2017, she and her colleagues worked with the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University to develop a logic model—a structured set of results they hoped to achieve—that guides the program to this day.

Since then, Panth and her colleagues have fielded several surveys to assess whether and how well Investment Connection was helping to create a bridge for nonprofits and funders to meet community needs. The results prompted the team to add meetings and other resources to the Investment Connection process. The goal is to build relationships and partnerships that strengthen the system within which CRA investments happen.

The St. Louis Fed’s District includes all of Arkansas and parts of six other states. That’s a lot of ground to cover. Results improve when the team gets to know a community before holding an Investment Connection event there. “Every Investment Connection has a coffee and conversation series in advance of it,” Panth said. “It allows us to understand the environment and to understand what relationships already exist and how we can leverage those for Investment Connection.”

The team gets high marks from other Reserve Banks for the quality of their CRA Investment Connection training. The St. Louis Fed provides information about the CRA, then bankers and nonprofits provide advice based on previous Investment Connection events. Both the in-person training and a series of six training videos build capacity and add value for nonprofits.

The team offers one-on-one coaching to be sure the pitch and the ask are on point. A lot of nonprofits want a grant, Panth said. Banks are more interested in loans. “We would say, we think you have assets that you can leverage towards a loan or a program-related investment,” Panth said. Of the types of funding made through their program so far, 45 percent are loans, 30 percent are grants, and 25 percent are equity investments.

“We invited foundations, corporations, and banks. We saw an immediate connection.” –Neelu Panth

In reviewing program participation, the St. Louis Fed team found that bankers and foundations were not talking to each other. “How do we increase communication?” Panth asked. “How do we grow the capital stack for nonprofits through diverse sources?” When a survey showed the need for funders—including more diverse funders—at the table for Investment Connection, the St. Louis team made that happen.

“We invited foundations, corporations, and banks,” Panth said. “We saw an immediate connection. A banker was saying, ‘I did not realize this funder was in the same neighborhoods working with the same organizations. How can we partner?’” Now named the St. Louis Community Development Funders Forum (CDFF), this group was inspired by a similar effort that the St. Louis Fed began in the Mississippi Delta region in 2019.

The CDFF meets every month. “We look at how to, as a diverse funding community, come together and look at our region from an aligned perspective and leverage federal and local funding,” Panth said. The forum also builds a cohort of funders likely to participate in future Investment Connection events.

“I kind of relish these opportunities,” Woodruff said of the chance to pitch funders at the St. Louis Investment Connection event.